- YayYo is a startup that plans to be an aggregator for ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft. It’s heavily marketing its IPO on television, and implying investors could make millions. YayYo’s founder has an unusual history involving an arms dealer, infomercials, charges of stock manipulation, and “Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus.”

“Ever heard of Uber or Lyft?”

The man on TV has well-coiffed gray hair and looks directly into the camera. Behind him, there’s a false backdrop of trading screens and skyscrapers. It’s an ad running on CNBC and Fox News for something called YayYo.

“Yes, YayYo,” the man says. The ad isn’t for its ride-hailing app. It’s for an initial public offering.

The man looks familiar, but his pitch is unusual.

You could make millions, like the early investors in Uber, he suggests. "Do it now. Before all the shares are gone."

Watching these ads, two questions come to mind:

- Can you actually do this? Is that the guy who played J. Peterman on "Seinfeld"?

The answer to both is yes. The actor's name is John O'Hurley. How it's possible that he's pitching shares in a risky startup on TV is more complicated. Even though the IPO is "qualified" by the Securities and Exchange Commission, the aggressive way YayYo shares are being marketed could be problematic, experts say, especially since the pitch is to mom-and-pop investors.

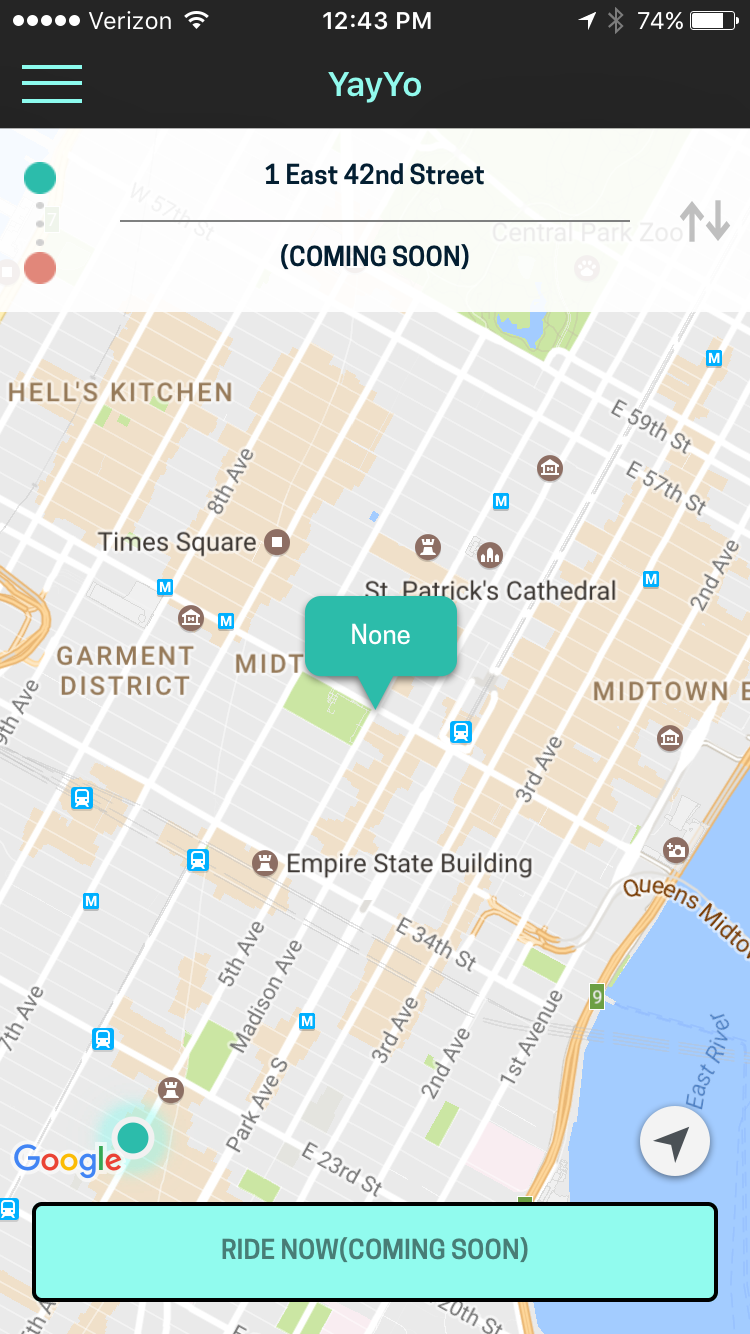

The company is a tiny startup with no working product, few staffers, but a big marketing budget. YayYo says it wants to be the Kayak of the ride-hailing industry, allowing you to compare prices and book rides on Uber, Lyft, and other such companies in a single app.

At the center of it all is Ramy El-Batrawi, whose life before starting YayYo involved working with an arms dealer, promoting "Men Are from Mars, Women Are From Venus," and ultimately to accusations of a stock-manipulation scheme that led to one of the biggest securities bailouts in history.

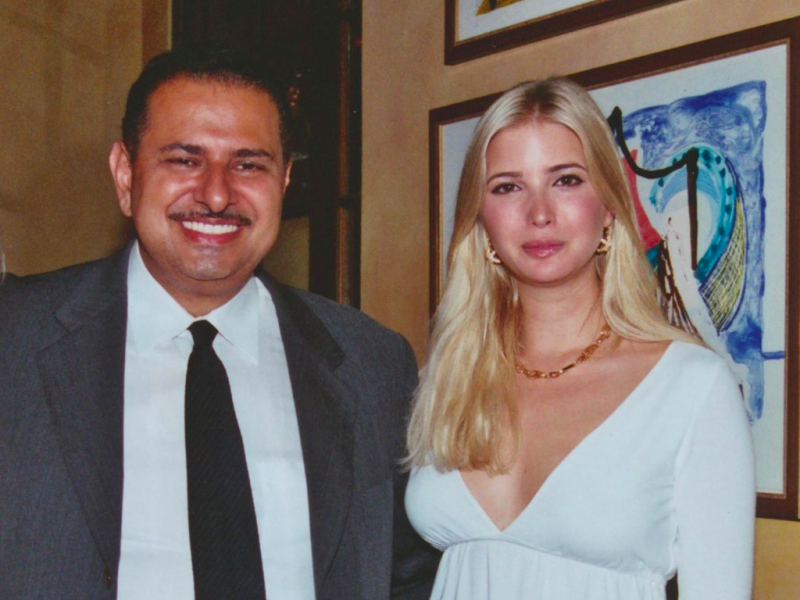

El-Batrawi never admitted wrongdoing but was barred from running a public company for five years, a steep comedown for a man who once proudly rubbed shoulders with the likes of Hugh Hefner, Ivanka Trump, and royalty as he sought to amass a fortune.

El-Batrawi is pitching investors on the YayYo IPO thanks to the 2012 Jumpstart our Business Startups, or JOBS Act. Meant to spur investment in smaller companies, it also allowed companies to pitch their IPOs on TV for the first time and created a new kind of mini-IPO whereby entrepreneurs can raise up to $50 million from just about anyone.

Hail YayYo

"If you would - write this in a positive way," El-Batrawi said in the third of a series of interviews with Business Insider, concerned about being portrayed negatively. He spoke with reporters over the phone and in person at his Beverly Hills office.

In those conversations, Batrawi said YayYo has big plans. In addition to its aggregator app, YayYo says it is gearing up to launch its own ride-hailing service with a fleet of luxury cars and salaried drivers behind the wheel.

"We are moving along in pretty good shape," he said.

But while YayYo aggressively solicits investors on TV, the company's products are far from ready, and some of his claims don't seem to stand up.

Launching the aggregator service is dependent on securing agreements with companies such as Uber and Lyft so that it can integrate those services' prices and available cars into the YayYo app.

El-Batrawi said in one conversation that those deals were on the way. YayYo is in "contact" with Uber and it has an "agreement" with Lyft, he said.

Uber and Lyft deny this.

"We sent YayYo a cease-and-desist letter several weeks ago and have suspended their access to Lyft," Adrian Durbin, a Lyft spokesman, told Business Insider. "I think it's fair to say that their CEO's characterization of our relationship is wildly inaccurate."

Uber has no deal of any kind with YayYo, according to Kaitlin Durkosh, a spokeswoman for Uber.

Later, El-Batrawi said the company never got Lyft's cease-and-desist order, and Bob Vanech, a YayYo board member, said it has some "clever strategies" to deal with the fact that Uber and Lyft are denying companies like YayYo access to their information. YayYo plans to partner with ride-hailing companies "three through 100," he said.

YayYo said it is planning a beta in the next couple of weeks.

"We work 18 hours a day," El-Batrawi said. "We know how close we are. It may feel like vaporware for some people. But the moment we start launching and generating revenue, which is not far along, our valuation is so much lower than what you would consider what Uber and Lyft is and everybody else."

The IPO, with a share price of $8, already values the company at $200 million.

Which brings us to those TV ads with John O'Hurley of "Seinfeld" fame.

'Scale faster'

"You might never have thought you'd be able to have a chance to invest in the new millennium movement of ridesharing," O'Hurley says infomercial-style to prospective investors in YayYo's ad announcing its IPO.

The YayYo spot boils down to this pitch: You probably missed out on investing in Uber and Lyft before they made investors millionaires. But because of the new SEC rule, YayYo is your chance for some ride-hailing riches.

"Because of YayYo's business model, YayYo can scale faster than any one of these ride-share companies can alone," the ad says. Experts say the implication that YayYo could become bigger than Uber is audacious enough to attract legal and regulatory scrutiny.

About 700 people have already invested, El-Batrawi says, with individual investments ranging from a single $8 share purchase to $100,000.

El-Batrawi says repeatedly that the ads target only professional, savvy investors who watch business-news channels like Fox Business and CNBC during the day.

But those networks also attract many hobby investors and retirees, and the ad's own script specifically speaks to small-time investors.

"With these new SEC rules, it makes it possible for the little guy like you or me to buy into an IPO previously unavailable," O'Hurley tells TV viewers.

Those new SEC rules are something called "Regulation A+," which was approved in March 2015 as part of the JOBS Act.

Grade A+

Regulation A+ made it easier for early-stage startups like YayYo to essentially crowdsource investment in a "mini-IPO." It's like Kickstarter, except investors become real shareholders.

The idea was to open startup investing to Main Street, as long as they don't put in more than 10% of their income or assets.

And as part of the rules, there are fewer requirements and regulations for companies like YayYo than if it were to do a full-fledged IPO.

There are actually two kinds of Regulation A+ offerings. In Tier 1, a company can raise up to $20 million from investors in a year. Importantly, Tier 1 is regulated more by individual states than the SEC. Tier 2 offerings, like YayYo, are larger - raising up to $50 million in a year - and though both require an SEC review, the latter offerings are not subject to review by the states.

To the public, that these offerings are submitted to the SEC might imply that it's a pretty good bet.

"That gives some comfort level to your average person," said Sam Guzik, a corporate-securities lawyer at Guzik & Associates. "That this is something that has been qualified by the SEC. Most people don't take the time to read the disclosure, and if they do, they are not going to understand or appreciate it."

For those who do wade through YayYo's SEC filings, which are comprehensive, just how risky this investment is becomes clear quickly.

The company's products are still in development, and much of its app is being developed by outside vendors under a licensing deal.

Without agreements in place with companies like Uber and Lyft, the filing says "the technical barrier to entry is steep."

YayYo has no history for investors to judge its prospects, and its executives have no history working together, or running similar companies. Its auditor says there's substantial doubt YayYo can continue as a going concern. At the end of October, YayYo had only about $160,000 cash on hand.

"This is a company on the edge," Peter Henning, a former SEC official and professor of law at Wayne State University, told Business Insider. "It's very risky, which they say it is. Should mom and pop be investing in this? You hope anyone investing in this is putting money in they're willing to throw away."

Some of those risk factors are typical of any early-stage "pre-revenue" company. Others that have done Regulation A+ IPOs include Elio Motors, which is working on an inexpensive three-wheeled car, and Knightscope, which designs robotic security systems. Either could fail, but both already have customers paying for their products or placing deposits.

At this point, YayYo is mostly marketing. El-Batrawi paid rapper Master P to write a promotional rap for the service, an ad that El-Batrawi showed Business Insider during a visit to the company's Beverly Hills offices.

But most of its marketing is targeting investors and those ads don't mention or allude to the risks. It's up to prospective investors to read through the dozens of pages of SEC filings to see what they're getting themselves into.

"Most people have fallen asleep by page two," Henning said. The SEC filing is "very intimidating."

And that's what worries experts and some regulators. Do investors really know what they're buying, and do they know who they're doing business with?

'My goal is to be that'

The life story of Ramy El-Batrawi, according to Ramy El-Batrawi, goes like this:

Born in Switzerland, he wound up in Montreal where, at age 12, after reading the Depression-era "Think and Grow Rich," he took to heart its message of not procrastinating wealth and left home. He hitchhiked his way to Tampa, Florida, because all the great rich guys were in America, El-Batrawi says.

He dropped out of high school, considering it another impediment to riches, and was homeless for the first five Florida years, partly living out of an old Cadillac, finding quarters on the street, recapping tires, and doing odd jobs, but he "tried not to work for anyone else."

Somehow, by 23, he says, he made his first million with a key-cutting business.

One day in the mid-'80s he was watching "Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous." The subject that day was Adnan Khashoggi, the high-flying arms dealer infamous for his profligate spending and role in the Iran-Contra scandal. At the time, Khashoggi was said to be the richest man in the world.

"My goal is to be that," El-Batrawi thought back then. "So when I saw him, I just decided that's the guy I need to work with."

As El-Batrawi tells it, he sold everything and spent a year searching for Khashoggi, tracking down his inner circle - including his psychic and chauffeur. El-Batrawi says he started paying some of Khashoggi's staff to tell him where he might find the man himself.

Finally, El-Batrawi said, after ingratiating himself, he landed his first assignment from the billionaire: buying a Miami-based aircraft-parts company called Jetborne.

Thus began what El-Batrawi nostalgically calls "the Khashoggi years," where he was the billionaire's No. 2 for nearly a decade, "negotiating transactions everywhere," meeting heads of states, sometimes holding multiple meetings in a single hotel lobby - "one in every corner" - he says.

The work he did with Khashoggi is also touted in his official bio in YayYo's SEC filing.

What was he selling then? "Different things. Russia needed airplanes," he says. There was a pipeline deal. "Whatever you can think of, we pretty much did."

El-Batrawi was living the good life. Even today, his social-media accounts are full of pictures from past decades: playing poker with Carl Icahn, standing next to former Los Angeles Clippers owner Donald Sterling. In the '90s, he met O'Hurley, who was dating a flight attendant on one of the private planes that El-Batrawi owned back then.

El-Batrawi said he was the one who introduced Donald Trump to Khashoggi at Olympic Towers when they were all in New York in the early '90s.

"It is interesting he became president," El-Batrawi said. "I would have never guessed that one."

Through all this, it's not completely clear how El-Batrawi made money. In court testimony from a case against Khashoggi, El-Batrawi says Khashoggi didn't pay him a salary but rather covered his travel expenses (at hotels, for instance) when they were doing deals.

Still, El-Batrawi had other ways to profit from his connection. When someone once paid $100,000 to introduce them to Khashoggi, who would, in turn, introduce that person to some princes, El-Batrawi took a $25,000 cut for making the connection, he testified in a separate court case in 2012.

'I wanted to be my own guy'

In the mid-'90s El-Batrawi set off on his own.

"I didn't want to always be Adnan's guy," he said. "I wanted to be my own guy."

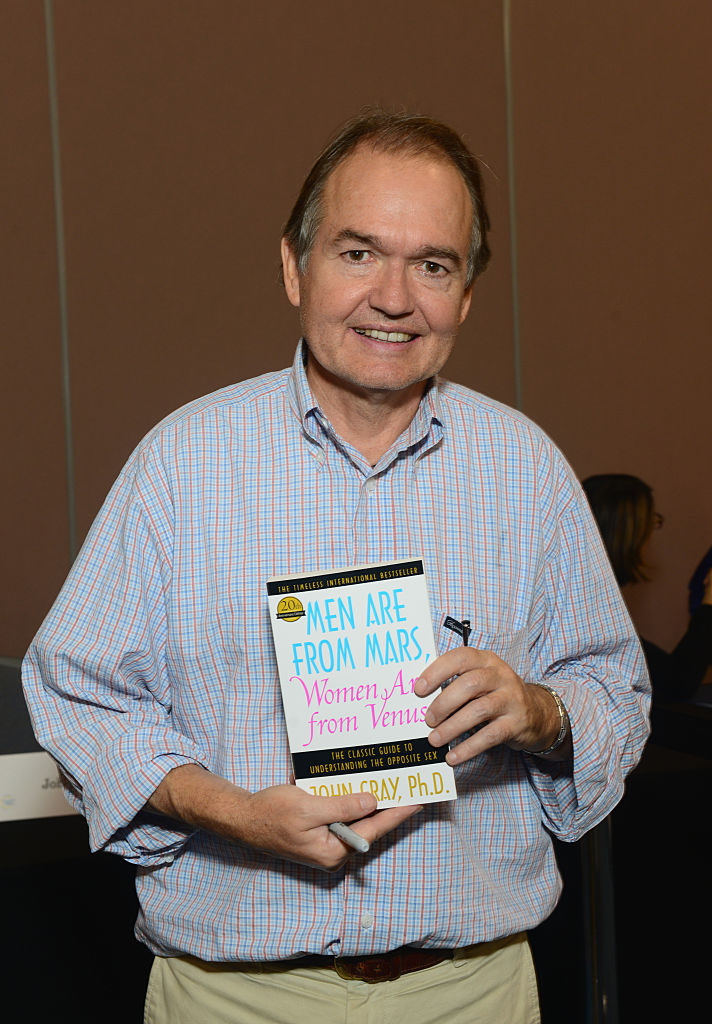

Around this time, El-Batrawi had some marital problems and read the book "Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus." It helped him, and he started going to seminars held by its author, John Gray.

He went up to Gray after one of the sessions and persuaded Gray to let him market the series, creating infomercials selling videos and other products tied to the hit self-help book.

"He was my first product," El-Batrawi said of Gray.

Gray calls El-Batrawi a master of infomercials.

Sales soared, and the two became friends. Gray even became a financial backer.

"Anything he does I would invest in," Gray said in an interview with Business Insider. "He's only brought me great success."

Gray invested in the company that sprang from the infomercials, GenesisIntermedia.

The company branched out into other products like ab workouts, and El-Batrawi says the company evolved into an "incubator" that acquired and built companies to market and spin off for a profit.

One was a network of "internet kiosks" for shopping malls called Centerlinq, and to market it, he turned, as he would time and again, to his friend John O'Hurley, most famous for his role as Elaine's eccentric boss on "Seinfeld."

It was the dot-com boom of the late '90s, and El-Batrawi was taking full part. In 1999, he took GenesisIntermedia public. El-Batrawi says Genesis was flying high.

A quick rise, and a quicker fall

"I'm hoping you write this one," El-Batrawi says as he rattles off stats about the company's post-IPO era. Revenues grew "exponentially." The stock was up "about 1,000 percent in two years."

That was true until it wasn't. Before long, the stock would be worthless, but Gray didn't lose faith in El-Batrawi.

"He's responsible. He's friendly, tremendous integrity," Gray says of El-Batrawi. Gray said he's also invested in YayYo.

The SEC had a different view.

In 2006, about four years after the company collapsed, the SEC charged El-Batrawi, along with Khashoggi and others, with manipulating GenesisIntermedia stock.

The SEC alleged that GenesisIntermedia lent its stock to brokers in exchange for cash and then engaged in a number of actions to prop up the stock's price. That included making thousands of trades "to create the false appearance of widespread investor interest," and hiring Courtney Smith, a bullish financial commentator who would appear on Bloomberg TV and CNBC.

Profits were funneled to Khashoggi through a Bermuda company called Ultimate Holdings, which then lent the shares to others, who were left holding the bag when the stock price tumbled from $25 a share to pennies.

In the government's charges, the actions resulted in $130 million in illegal profits and the largest bailout in the history of the Securities Investor Protection Corp., wiping out several middlemen brokerages, like MJK Clearing in Minnesota.

El-Batrawi said in a 2009 deposition that he was "trying to make [Khashoggi] money to prove that I was kind of - he was like my mentor - and I really looked up to him."

The case was settled in 2010. The SEC barred El-Batrawi and Khashoggi from running public companies for five years. Neither admitted nor denied wrongdoing.

Courtney Smith, the TV commentator, was acquitted of charges against him. He's now a consultant for YayYo.

El-Batrawi dismisses the charges he faced, and he has long blamed an FBI agent and stock manipulator for dooming his company.

"9/11 hit," El-Batrawi said. "Arabs were a good target for people at the time, the SEC and all of that. They filed the lawsuit after five years before the statute of limitations ran out because they couldn't find anything wrong. And after battling for seven years we just ended up with a consent decree ... It wasn't fraud then, it isn't fraud now … At the end, they found the people were who shorting the stocks were hired FBI agents."

More recently, in an unrelated 2014 case, investors sued El-Batrawi, alleging that he misled them about an investment in a multilevel-marketing company that El-Batrawi controlled called Xerveo, which sold diet products. The case was later settled, California court documents show.

'It'll keep going higher'

You won't find YayYo's name in the visitor's directory at 9665 Wilshire Blvd. in Beverly Hills, but if you head down a drab hallway on the eighth floor, you'll see a sign that says "YAY YO."

Walk right in (no one answers the door) and you'll find four people sitting around a long table.

At center is El-Batrawi, surrounded by a programmer, a back-end-operations guy, and a car-service coordinator.

In a room across the hall, women wearing headsets answer calls from prospective investors.

YayYo looks like a lot of startups do. Staffers wear T-shirts and jeans. Plans are scribbled across whiteboards.

An ad for the YayYo IPO has just aired on TV, and El-Batrawi pulls up the website's analytics. The number starts soaring: 177, 290, and then over 500 people on the site all at once.

"As soon as [O'Hurley] finishes talking, then it really accelerates," El-Batrawi says. "It'll keep going higher."

'For the little guy like you or me'

If you're wondering, El-Batrawi said he didn't know that "yayo" is sometimes slang for cocaine. He wanted a catchy name, "like Google," but also one that's easily pronounced in Chinese, where he wants to expand.

"We have 100 times more positive comments on it than negative comments. It's very memorable."

But it's what O'Hurley says in the ad that could get YayYo into trouble.

"There are really only two rules," Sara Hanks, a former SEC official, CEO and founder of CrowdCheck, told Business Insider. "Don't lie, and don't say anything that is misleading in any way."

But what's "misleading" is somewhat subjective.

"You know it when you see it," Hanks said.

Legal experts had varying views of where the line is, but identified specifics in YayYo's ad they would generally advise clients avoid:

- The company compares itself to specific successes like Uber and Kayak, implying YayYo will be similar. It talks specifically about "millions of dollars," providing a sense of possible profit. It includes a misleading sense of urgency, suggesting the shares will soon run out, without the context of why it's a limited offering. It's unbalanced. There's no mention of risk factors and that the company could fail.

Vanech, the board member, said the ad was approved by lawyers, and then filed with the SEC, which contacted YayYo's attorneys and requested changes to the visual background behind O'Hurley, which had imagery that looked too much like the New York Stock Exchange and the SEC logo. He said regulators did not object to the script. The SEC declined to comment.

It's all about that marketing budget

Most companies go public when they've already proved something, like sales or a promising drug in development.

"YayYo's advantage is that they have a substantial marketing budget," Darren Marble - CEO of CrowdfundX, which does marketing for companies doing Regulation A+ IPOs - told Business Insider. Based on the number of times the ad has played, YayYo's ad spending is likely hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The ad has run at least 33 times nationally since it debuted on April 19, which cost the company at least $111,000, according to analytics company iSpot, which tracks only national airings. The ad has likely run far more times on DirecTV, which reaches a sizable portion of the population.

Mini-IPOs like YayYo's are still novel. To some, they already have a stigma: Why can't the company raise traditional venture capital, they wonder. But proponents say a successful Regulation A+ can raise millions of dollars without founders having to give up control to outside investors.

But if these early years of Regulation A+ are marked by failures, it could cast a permanent pall over these kinds of offerings.

"Regular investors are the ones that can fall for a scam," Henning of Wayne State University said.

When lawmakers were debating the JOBS Act, some state regulators objected, saying it could put small investors at risk. Two states sued because the JOBS act reduces states' ability to police deals.

If YayYo had decided to do an offering pre-JOBS Act, it would have come under state regulators' control. A few states assess the "merit" of mini-IPOs, and some may have objected to YayYo's ads.

"Generally speaking, as a state regulator, when we have the authority to review, we will object to ads when a startup or smaller company compares itself to a larger, well-established company," said Faith Anderson, chief of registration and regulatory affairs for the securities division of the Washington State Department of Financial Institutions.

Some states, such as Massachusetts, may have denied the entire YayYo offering because the company has no track record, no independent directors, or because of El-Batrawi's history with the SEC.

But in larger filings, like YayYo's, it's only the SEC, not the states, in control.

El-Batrawi's past SEC action must be disclosed - it's in the filing - but it won't stop him from offering the IPO, because it occurred before the JOBS Act was passed.

All this is slowing Regulation A+'s rise into the mainstream.

"I don't believe that the regulation is inherently flawed; I think that it will take some time before we see quality companies using it," said Cass Sanford, a lawyer at Sichenzia Ross Ference Kesner LLP.

'It really is up to the public to decide'

Past performance is no indication of future results. El-Batrawi's colorful past doesn't mean YayYo isn't real. It's no doubt a highly risky investment, but its executives say they are true believers.

"That is our intention here: to build a great company," Vanech said.

Yet there are other questions. El-Batrawi says he's also a 10% investor in a mysterious biotech startup called NeurMedix that plans its own Regulation A+ IPO shortly, complete with O'Hurley on the offering page.

El-Batrawi also owns an aerospace-parts company called Advanced Tek Group, which is planning a mini-IPO soon. The details of that company are vague, but O'Hurley makes an appearance there too.

And while El-Batrawi may have cleaned up his act, domain-name records show he owns a number of websites promoting the three IPOs and featuring articles about himself as an "up-and-comer." El-Batrawi wouldn't comment. Records show he also owns fuckyouall.net.

"We are doing everything we can to comply with all laws, to follow the SEC guidelines, to use best practices, to give individual investors the chance to get in at the ground floor," Vanech said in the final interview. He said this level of "journalistic scrutiny at this stage of the business" is unwarranted.

And to Ramy El-Batrawi, his past and YayYo's prospects are all fully disclosed to investors.

"There are a lot of risks in this. But there is a lot of upside if we do execute. This is what people are betting on," he said. "It really is up to the public to decide if this is for them or not."

Additional reporting by Frank Chaparro, Rebecca Harrington, and Lydia Ramsey.