- Scientists are racing to learn more about the coronavirus that emerged in Wuhan, China in December.

- Preliminary research suggests that Wuhan alone could have 19 times more cases than reported, possibly even 26 times more.

- Other studies – some of which have not been peer reviewed – suggest that patients could experience nausea or diarrhea before they get fever or a cough.

- Many people infected with the new coronavirus have mild symptoms or none at all, making it difficult to know the size or severity of the outbreak.

- For the latest case total, death toll, and travel information, see Business Insider’s live updates.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Scientists are racing to learn more about a new coronavirus that has swept through China and spread across the globe. In the last few weeks, scientists worldwide have published a wealth of early studies.

The virus, which may have jumped from animals to people at a market in the city of Wuhan, has killed more than 2,000 people and infected more than 75,000.

The World Health Organization (WHO) considers the outbreak a global public-health emergency – a declaration that has only been used five times since it was created in 2005.

Research about the coronavirus so far has appeared both in peer-reviewed journals and on pre-print servers without peer review, since that process can take months, and the outbreak has grown quickly.

Although it's preliminary, here's what published research has shown so far.

The largest analysis yet of coronavirus patients so far found that about 80% of cases in China are mild.

The new report from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention looked at 72,314 cases.

Patients with mild symptoms might experience a fever or dry cough, but they aren't likely to have difficulty breathing or develop a severe lung infection within 24 to 48 hours.

Many people on a quarantined cruise ship who tested positive for the new virus, called COVID-19, never showed symptoms at all.

The Diamond Princess cruise ship has been host to the largest number of diagnosed COVID-19 cases outside China: at least 621.

In a quarantine that many experts have called ineffective and unethical, officials kept passengers and crew on the ship while they tested them. The virus seems to have spread on the ship during that time.

Of the 621 cases on board, 322 showed no symptoms, according to Japan's Ministry of Health.

Those people could still develop symptoms later, but they might also offer evidence that many coronavirus carriers throughout China are going undetected, since they might not go to the hospital if they don't feel sick.

The period of time during which people carrying the coronavirus show no symptoms, called the incubation period, seems to last two to 14 days.

That's the assumption that the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has adopted, based on the incubation period of MERS.

It's also the reason the White House decided to temporarily bar foreigners from entering the US if they have been to China within the past 14 days. US citizens who have been to the Hubei province of China - where Wuhan is located - within the prior 14 days could be quarantined for up to two weeks upon their return.

These policies, which went into effect on February 2, are meant to prevent people from spreading the virus before they know they've been infected.

But an analysis of over 1,099 patients found that some had incubation periods as long as 24 days.

That study has not been peer-reviewed, though.

It's unclear whether people who are infected can spread the new coronavirus before they show symptoms.

A letter in The New England Journal of Medicine described a case in which a 33-year-old German man caught the coronavirus from a business partner from China. Three days later, he felt better and went back to work (before realizing he'd had the coronavirus), then infected at least two of his colleagues.

But a follow-up letter from Germany's public health agency claimed that the researchers hadn't spoken with the business partner from China. The agency said she had told investigators she had symptoms while in Germany, according to the journal Science.

There is no evidence that SARS or MERS can spread from people who don't have symptoms. But preliminary research shows that less serious coronaviruses might.

A study published without peer review looked at common coronaviruses, which cause nothing more than a cold, and found them inside nasal passages of people who reported no symptoms.

"It's going to leak out as they're speaking and breathing and coughing and sneezing and wiping their nose," Jeffrey Shaman, the lead author of that study, told NPR. "Whether it's ... a sufficient quantity to make somebody else infectious, we can't discern that from what we've done."

Men represent the majority of new coronavirus cases so far, and they seem to die more often from it.

The study from China's CDC found that men are more likely to die of the virus, with a fatality rate of 2.8% compared to 1.7% for women. Men also represented a slight majority of cases: around 51%.

Other recent studies have yielded similar results. A study of nearly 140 coronavirus patients at a Wuhan University hospital found that the virus was most likely to affect older men with preexisting health problems. More than 54% of the patients in the study were men, and the median age of patients was 56.

A study of 99 coronavirus patients at Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital showed that the average patient was 55.5 years old, and men represented around 68% of the total cases. A third study of nearly 1,100 coronavirus patients (which is still awaiting peer review) identified a median age of 47, with men representing around 58% of the cases.

Some experts think that's because Chinese men smoke more than Chinese women, increasing their risk of respiratory problems.

On Friday, the executive director of the World Heath Organization's Health Emergencies Program, Michael Ryan, said smoking was "an excellent hypothesis" for why the virus has affected more men. A 2010 national survey of smoking in China found that 62% of Chinese men had been smokers at some point, while only 3% of Chinese women had ever smoked.

"Since COVID-19 is a respiratory disease and often causes pneumonia, having a history of smoking could increase the risk of more severe respiratory distress or pneumonia," Saskia Popescu, an epidemiologist at the Honor Health medical group in Arizona, told Business Insider.

More data is needed to confirm the theory, though.

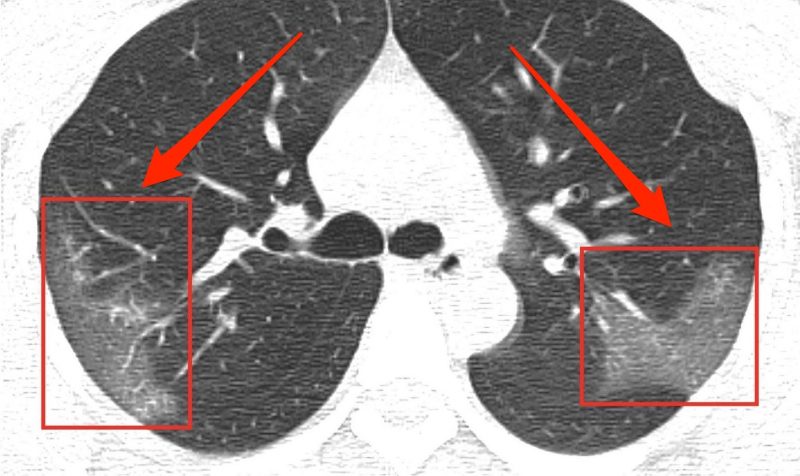

Patients with severe cases of the virus develop pneumonia-like symptoms. Many have a build-up of fluid in their lungs.

A study released in the journal Radiology included scans of the chest of a 33-year-old woman from a hospital in Lanzhou, China. The scans show white patches in the lower corner of her lungs, which indicate what radiologists call "ground glass opacity."

"If you zoom in on the image, it kind of looks like faint glass that has been ground up," Paras Lakhani, a radiologist at Thomas Jefferson University who was not involved in the study but examined the images, told Business Insider. "What it represents is fluid in the lung spaces."

Though the coronavirus is a respiratory disease, some research suggests it might also affect the digestive system.

In a study shared in the pre-publication repository biorXiv without peer review, researchers in Shanghai detected an enzyme signature of the virus in cells from the small intestine and colon.

Researchers detected the coronavirus' RNA in a US patient's poop.

Dr. Susan Kline, spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America, told MedPage Today that other coronaviruses appear in poop as well. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) traveled through a Hong Kong apartment's sewage system and infected other residents after one sick person had diarrhea.

Kline said some health authorities may be overlooking gastrointestinal symptoms, like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

The first US patient to be diagnosed had diarrhea and reported abdominal discomfort the day after he arrived at the hospital. Patients in China and Vietnam have also had diarrhea, vomited, or reported nausea.

Kline said that although healthcare workers should not expect all patients to have gastrointestinal problems, including those symptoms in official guidelines could help catch more coronavirus cases early on.

"That would be helpful for clinicians to have, so they could at least consider that a patient with novel coronavirus might have vomiting or diarrhea," Kline said.

Ignoring those rarer symptoms could have deadly consequences, since they are sometimes the first indicators that a person is infected.

One study said a patient was placed in a surgical ward because they only showed abdominal symptoms, so doctors didn't suspect the new coronavirus. That patient transmitted the virus to at least 10 healthcare workers and four other patients in the ward.

The outbreak poses a grave risk to Chinese healthcare workers. Officials have reported 1,716 healthcare workers infected nationwide.

China's National Health Commission announced Friday that 1,716 health workers had contracted the new virus. At least seven have died.

Of the total number of reported sick healthcare staff, 87.5% are in the Hubei province, where the outbreak began.

Research published earlier this month in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) found that, of 138 patients studied at one hospital, 29% were healthcare workers.

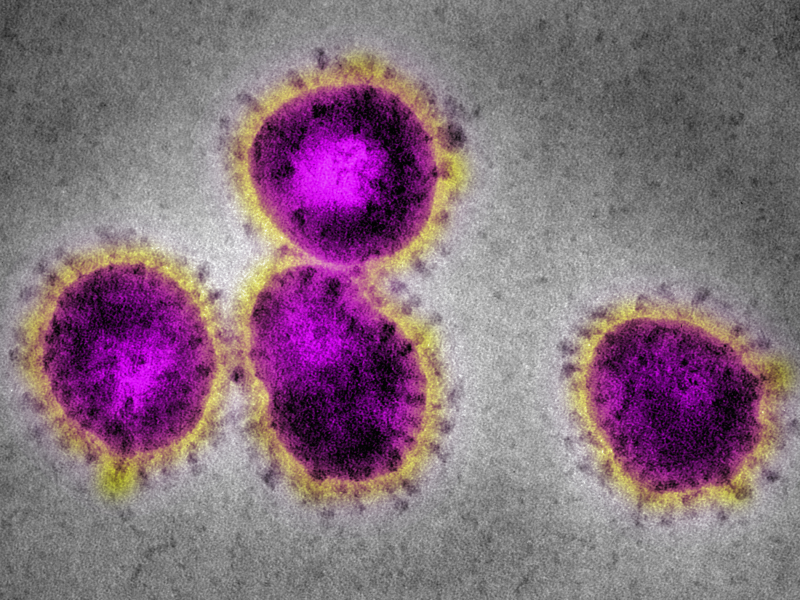

COVID-19 is the seventh known member of the coronavirus family, which also includes the viruses that cause the common cold and pneumonia.

Other coronaviruses include SARS and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS).

Though it has spread quickly, the new coronavirus so far seems less deadly than MERS and SARS.

So far, the mortality rate for the Wuhan coronavirus is around 2%, but experts think that rate will evolve.

The new coronavirus appears to be more infectious than SARS. Studies looking at the number of people an average patient infects suggest it could range from one to five.

Knowing how many people the average patient infects - a number called the R0 (pronounced R-naught) - is crucial to understanding how a virus spreads.

So far, studies vary widely on the R0 of the Wuhan coronavirus. Most estimates, including the WHO's, land in a range similar to that of SARS, about two or three. But some studies have placed the R0 much higher, closer to five or six.

One peer-reviewed study estimated that 75,815 people in Wuhan had likely been infected by January 25 — nearly eight times the number of reported cases worldwide at the time.

The study, published in medical journal The Lancet, estimated that infected people would pass the virus to two to three others, on average, meaning the infected population would double every 6.4 days.

The researchers even accounted for the quarantine China imposed on Wuhan and surrounding cities.

"Other major Chinese cities are probably sustaining localized outbreaks," the study authors wrote. "Large cities overseas with close transport links to China could also become outbreak epicenters, unless substantial public-health interventions at both the population and personal levels are implemented immediately."

A more recent analysis estimated that only one in 19 infected people in Wuhan have been tested and diagnosed.

The analysis, from researchers at Imperial College London, is based on estimates of the rate of infection in cases outside of mainland China.

The researchers looked at roughly 750 passengers who traveled from Wuhan back to their home countries on government-arranged flights. Upon their return, the travelers were all kept in isolation and tested for the coronavirus immediately. Many tested positive, though some didn't present any symptoms.

The researchers applied the rate of infection calculated in those situations to the population of Wuhan. They assumed that the virus would show up on a test for an average of 14 days.

The same study found that if the virus is only detectable for seven days, the number of cases in Wuhan could be even higher: 26 times the reported number.

In that scenario, the researchers calculated Wuhan would have 300 new cases per every 100,000 residents on January 31. In total, that would be 33,000 new cases in the city that day.

When the analysis was published, the Chinese government had reported just 19,558 cases total.

Since that study came out, the number of reported cases spiked significantly as health officials revised the way they counted cases.

In its update on February 13, the Hubei Health Commission added 14,800 people to its list of cases and reported 242 additional deaths.

The commission said the jump was due to a change in the way cases were counted: The newer number included clinical diagnoses made via CT scans of patients' lungs in addition to lab-test results.

The virus likely spread far beyond quarantined cities before China cut off transportation, according to some studies.

On January 23, local officials quarantined Wuhan by shutting down all public transportation - including buses, metros, and ferries. Trains and airplanes coming into and out of the city were also shut down, and roadblocks were installed to keep taxis and private cars from exiting.

With restrictions and quarantines in other cities, more than half of China's population is under some sort of travel restriction, according to a CNN analysis.

But a paper published in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases found a 99% chance that at least one person carried the virus to the major cities of Beijing, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Shanghai before Wuhan's quarantine started.

The study also found that there was a 50% chance that people carrying the virus had traveled to at least 128 cities in China before the quarantine began.

"Given that 98% of all trips during this period are taken by train or car, our analysis of air, rail, and road travel data yields more granular risk estimates than possible with air passenger data alone," Lauren Ancel Meyers, a co-author of the paper, said in a press release.

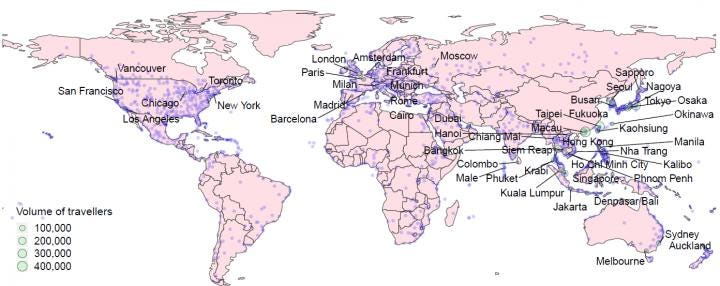

Bangkok, Thailand is more at risk than any other city outside China as the virus spreads, according to an analysis by population-mapping experts.

That's because the researchers estimated that Bangkok would receive over 1 million air travelers from China's most affected cities over a three-month period, starting 15 days before the Lunar New Year.

Thailand has so far reported at least 35 cases of the virus.

After Bangkok, that analysis identified Hong Kong, Taipei, Sydney, New York, and London as other high-risk cities.

The most at-risk countries were Thailand and Japan. The US placed sixth in the researchers' ranking.

"It's vital that we understand patterns of population movement, both within China and globally, in order to assess how this new virus might spread domestically and internationally," Andrew Tatem, a professor at the University of Southampton and a study co-author, said in a press release.

While researchers on the frontlines learn more about infected patients, others are tracing the new coronavirus back to its source, which seems to be bats.

A genetic analysis of coronavirus samples from nine patients revealed it to be closely related to two SARS-like coronaviruses that came from bats.

Bats were the original hosts of SARS; the animals have been known to pass diseases to other species via their poop or saliva, and the unwitting intermediaries can transmit the virus to humans.

Another genetic assessment found that the new coronavirus is more genetically similar to SARS-like viruses in bats than to human SARS or MERS.

The analysis compared three genomes from the new coronavirus to many human SARS genomes, MERS genomes, and genomes from SARS-like coronaviruses in bats. The new coronavirus was most similar to the bat samples.

One study suggested that the virus jumped from bats to snakes to humans, but other researchers said that's unlikely.

In a peer-reviewed study published January 22 in the Journal of Medical Virology, a group of researchers in China suggested that snakes were the most likely animals to have passed the virus to humans.

Many scientists voiced their disagreement, however.

"They have no evidence snakes can be infected by this new coronavirus and serve as a host for it," Paulo Eduardo Brandão, a virologist at the University of São Paulo who is investigating whether coronaviruses can infect snakes, told Nature. "There's no consistent evidence of coronaviruses in hosts other than mammals and Aves (birds)."

Virologist Cui Jie, who was on a team that identified SARS-related viruses in bats in 2017, said this strain from Wuhan is clearly a "mammalian virus."

"Nothing supports snakes being involved," David Robertson, a virologist at the University of Glasgow, told Nature.

One group of researchers suggested that bats may have passed the virus to pangolins, which then passed it to humans.

Researchers from South China Agricultural University in Guangdong suggested that the coronavirus' intermediate host might have been the pangolin, an endangered mammal.

According to China's Xinhua news agency, the researchers found that samples of coronaviruses taken from wild pangolins and from infected patients are 99% identical.

But this research has yet to be published or confirmed by other experts.

Other possible intermediaries include pigs and civets.

Another genetic study of the coronavirus found that it shares 80% of its genome with SARS — enough that research to develop SARS treatments and vaccines could be applicable here.

"In essence, it's a version of SARS that spreads more easily but causes less damage," Ian Jones, a virologist at the University of Reading in the UK who was not affiliated with the study, said in a press release.

He added: "This indicates that treatments and vaccines developed for SARS should work for the Wuhan virus."

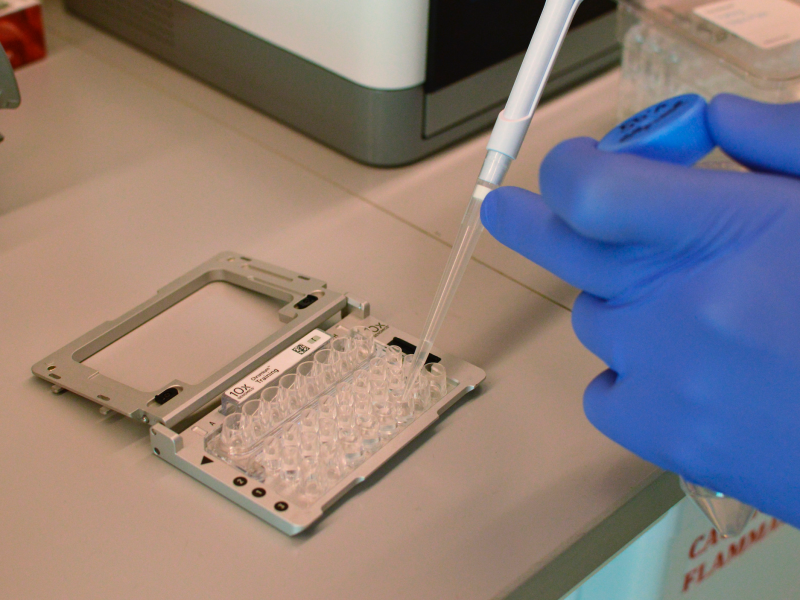

Growing the virus in a lab could help identify the antibodies humans produce before they show symptoms, and possibly help develop a vaccine.

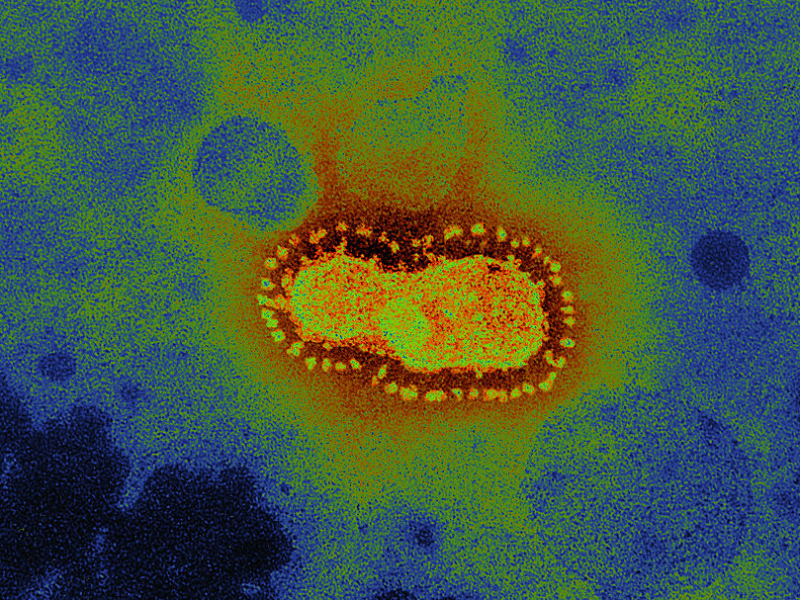

This video, courtesy of Dr. Julian Druce at the Victorian Infectious Diseases Reference Laboratory, shows the Wuhan coronavirus that Australian scientists grew from a patient sample at the Doherty Institute. It's the first time a lab outside China has grown the virus.

The lab-grown sample could help identify people who aren't yet showing symptoms but are still infected and capable of spreading the virus.

"An antibody test will enable us to retrospectively test suspected patients so we can gather a more accurate picture of how widespread the virus is, and consequently, among other things, the true mortality rate," Dr. Mike Catton, deputy director of the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, said in a statement. "It will also assist in the assessment of effectiveness of trial vaccines."

While some researchers are looking for a vaccine, others are developing treatments. Clinical trials are testing HIV medications against the new virus.

Johnson & Johnson, AbbVie, and Gilead Sciences have all donated antiviral drugs to Chinese health authorities to run tests against the virus.

There are 31 clinical trials testing various drugs, mainly antiviral therapies, against the coronavirus, BioCentury reported.

If effective, these drugs could be a short-term solution while companies race to develop vaccines. Those efforts will likely take longer because vaccines typically require multiple rounds of clinical testing that can span several years.

The first US patient received an experimental drug called remdesivir.

The treatment appeared effective, though the researchers who reported the case said more robust testing is needed. Remdesivir was initially developed to fight Ebola.

Gilead, the biotech company that developed remdesivir, has donated enough of the drug for 500 patients to Chinese health officials. The company is working with local hospitals to run tests, Merdad Parsey, Gilead's chief medical officer, told Bloomberg.

The study from China's CDC suggested that the outbreak may have peaked in early February.

The study authors examined cases of the virus from December 8 to February 11. Their results showed that the largest number of coronavirus patients started exhibiting symptoms on February 1.

Since then, there haven't been as many new illnesses, the authors found. That could be a sign that the outbreak is tapering off.

But the authors also warned that China should prepare for a "possible rebound of the epidemic."

What's more, a study published without peer review found that the new coronavirus thrives in temperatures of 13 to 24 degrees Celsius (55 to 75 Fahrenheit). That means that the virus could spread more easily to cities in northern China as spring arrives.

"From a global perspective, cities with a mean temperature below 24 degree Celsius are all high-risk cities for [COVID-19] transmission before June," the authors wrote.

"Beyond all, this global health threat teaches, once again, that it is far better to invest in preparedness to prevent, rapidly identify, and contain outbreaks at their source," Georgetown University researchers wrote.

In their analysis of government responses to the virus, published January 30 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, they added: "Reacting after a novel infection has spread widely (perhaps overreacting with travel bans and quarantines) costs lives, economic resources, and the well-being of millions of people currently cordoned off in a zone of contagion."

Correction: A previous version of this post used a chart with inaccurate data about the 2009 H1N1 outbreak. It has been removed.

- Read more:

- Thermometer guns used to screen for coronavirus are 'notoriously' unreliable experts say, warning about improper use and false temperatures

- The US has confirmed 15 coronavirus cases across 7 states. Here's what we know about all the US patients.

- The outbreaks of both the Wuhan coronavirus and SARS likely started in Chinese wet markets. Photos show what the markets look like.

- The novel coronavirus seems to have a low fatality rate, and patients are making full recoveries. Experts reveal why it's causing panic anyway.

- 'Wholly inappropriate' quarantine practices may have helped spread coronavirus on the Diamond Princess cruise ship, experts say