Phil Walter/Getty Images

- The full Buck Moon may appear blood red in skies across the US this weekend, due to wildfire smoke.

- Western wildfires driven by climate change have spread smoke to the East Coast, tinting skies orange.

- Wildfire smoke is a huge health risk, and widespread-smoke events will likely become more common.

- See more stories on Insider's business page.

A full Buck Moon is rising this weekend, and it may appear orange or blood red in skies across North America.

Normally, the moon turns orange or red during an eclipse, when Earth blocks sunlight and our atmosphere reflects red light onto the lunar surface instead. But this time is unusual. Instead of being eclipsed by Earth's shadow, the moon may be eclipsed in many places by layers of smoke.

Wildfires have exploded across the Pacific Northwest over the last month, fueled by dry vegetation and a series of heat waves made possible by the warming climate. The largest, Oregon's Bootleg Fire, has grown to nearly twice the size of New York City and started generating its own weather.

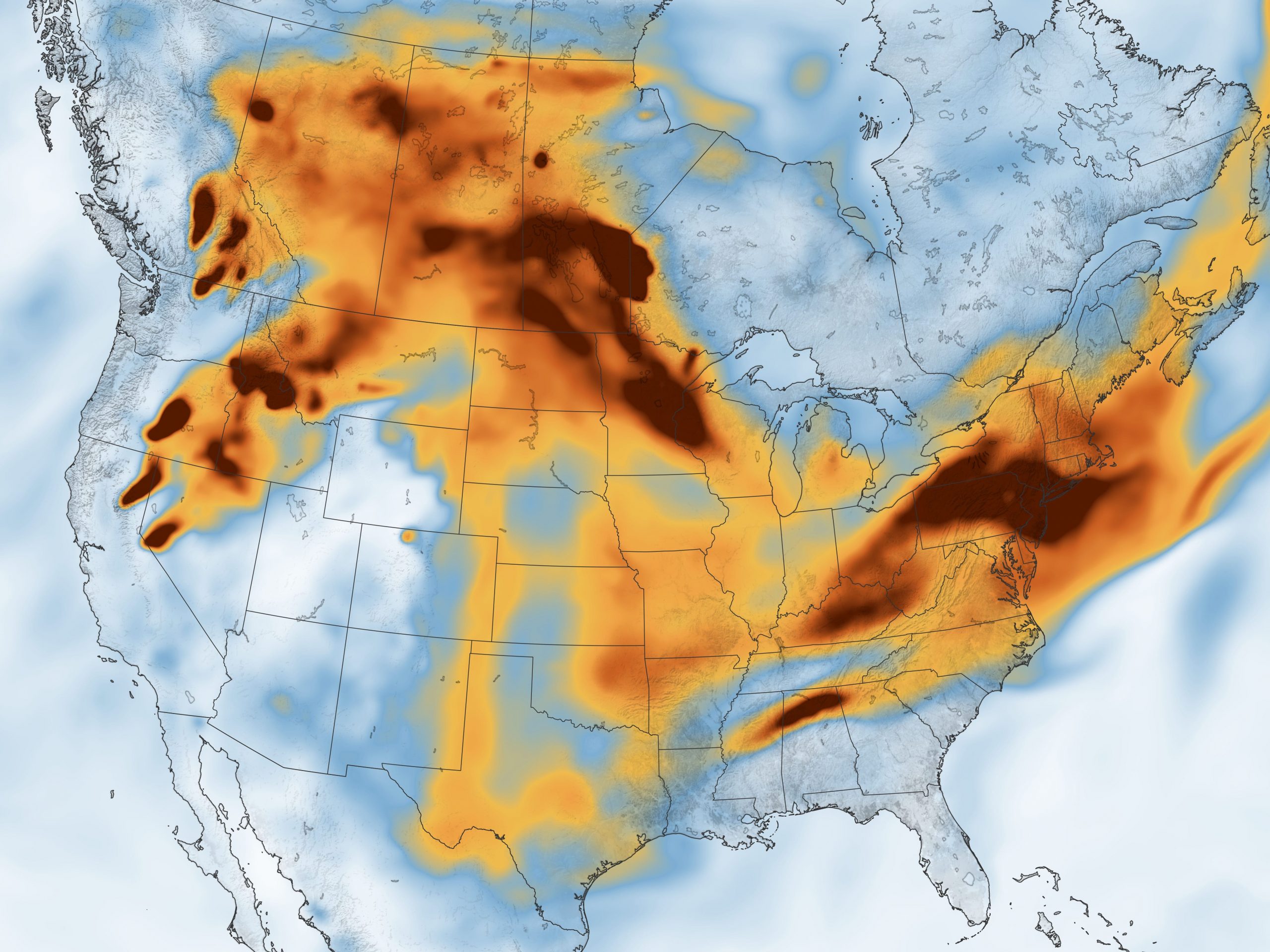

The blazes are sending smoke roiling across the continent, prompting air-quality alerts from Minnesota to North Carolina and tinting skies orange as far east as New York and Washington, DC.

NASA Earth Observatory/Joshua Stevens/GEOS-5/NASA GSFC

That's because the particles in wildfire smoke block shorter wavelengths of sunlight – the blues and greens – and allow the longer, redder wavelengths to pass through. The moon will be no exception to this paintbrush of sweeping smoke.

"When you do have wildfire smoke, especially high up in the atmosphere, you typically do see your moon kind of turn reddish or orange," Jesse Berman, an assistant professor in environmental health at the University of Minnesota, where he studies extreme weather and air pollution, told Insider.

If the smoke is low and thick enough, it could block out the moon entirely. But, Berman said, "it's very likely that any area experiencing a wildfire-smoke exposure can see this red or orange moon."

Andrew Kelly/Reuters

The moon will appear full Thursday night through Sunday morning, peaking on Friday night, according to NASA.

In the month of July, the full moon is often called the Buck Moon. According to the Old Farmer's Almanac, this name comes from the Algonquin peoples, who share a family of languages and originate from the area that today ranges from New England as far west as Lake Superior. The name refers to buck deer's antlers emerging in summer.

Widespread wildfire smoke could become common

David Ryder/Reuters

Wildfires that produce continent-sweeping smoke clouds could become annual events, if not occurring "multiple times every single year," Berman said.

"We do expect these events to become not only more frequent, but possibly more severe in the future as our climate tends to shift towards drier conditions, to hotter conditions, to areas where you have less frequent rainfall," he added. "Every one of these wildfire events is an opportunity for that smoke to travel long distances and affect not only the people nearby, but also those very far away."

Bootleg Fire Incident Command via AP

If smoke stays high in the atmosphere, it probably won't affect air quality for people on the ground. However, it sometimes falls back down and fills the air we breathe with hazardous particles - hundreds or even thousands of miles from the fire that created it.

The microscopic particles in wildfire smoke can penetrate deep into the lungs and even the bloodstream. Research has connected wildfire-particle pollution to an increased risk of heart attack, stroke, and premature death.

In healthy people short-term, it can irritate the eyes and lungs and cause wheezing, coughs, or difficulty breathing. Young children, the elderly, and people with preexisting conditions like asthma or COPD are particularly vulnerable to more serious effects.

As smoke wafts over his Minnesota home, Berman has had his two young children play inside instead of going to the park. The US Environmental Protection Agency recommends keeping doors and windows closed when wildfire smoke is impacting air quality, and designating a "clean room" with a portable air cleaner and no cooking, smoking, or candle-burning.

"Right now, nothing has shown that the conditions are going to become markedly better in the future," Berman said. "Instead, we're really predicting that conditions are going to continue to get worse."

"It doesn't matter where you're living," he continued. "You can be affected by these events the same as anyone else."