- The Milky Way galaxy has billions of planets that could potentially host life. Yet despite scientists’ efforts to monitor for and occasionally signal to extraterrestrials, we have not found any evidence that aliens exist.

- This conundrum is known as the Fermi Paradox, and it has inspired debate among researchers for decades.

- A co-winner of this year’s Nobel prize in physics said he “can’t believe we are the only living entity in the universe,” and that he’s “absolutely convinced” we will detect alien life within 100 years.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Didier Queloz, a physicist from the University of Cambridge, was named a co-winner of the Nobel prize in physics on Tuesday for his discovery of the first planet outside our solar system orbiting a sun-like star.

Queloz, who calls himself a “planet hunter,” said following the award ceremony that his work has led him to become “absolutely convinced” that humans will detect alien life in the next 100 years.

“I can’t believe we are the only living entity in the whole universe. There’s just way too many planets, way too may stars … the chemistry that led to life has to happen elsewhere,” Queloz in a talk at the Science Media Center in London on Tuesday.

His statement is, in a way, a response to a question that physicist Enrico Fermi first posed to his colleagues over lunch in 1950: “Where is everybody?”

Arguably, Fermi said, in the 4.4 billion years it took for intelligent life to evolve on our planet, the rest of our galaxy should have been overrun with similarly smart, technologically advanced aliens. But scientists have been monitoring radio waves for signs of alien life in the universe for decades, and they haven't found anything or anyone.

This conundrum has come to be known as the Fermi Paradox.

Scientists have offered myriad potential answers to Fermi's question, including that aliens are hibernating or deliberating hiding from us. Some researchers have also suggested that highly advanced technological civilizations destroy themselves before they have the opportunity to get in contact with other intelligent life in the universe.

In his recent book "End Times," science writer Bryan Walsh discusses 13 theories as to why we've yet to make contact with aliens and why we might never do so. Here's how each one addresses the Fermi Paradox.

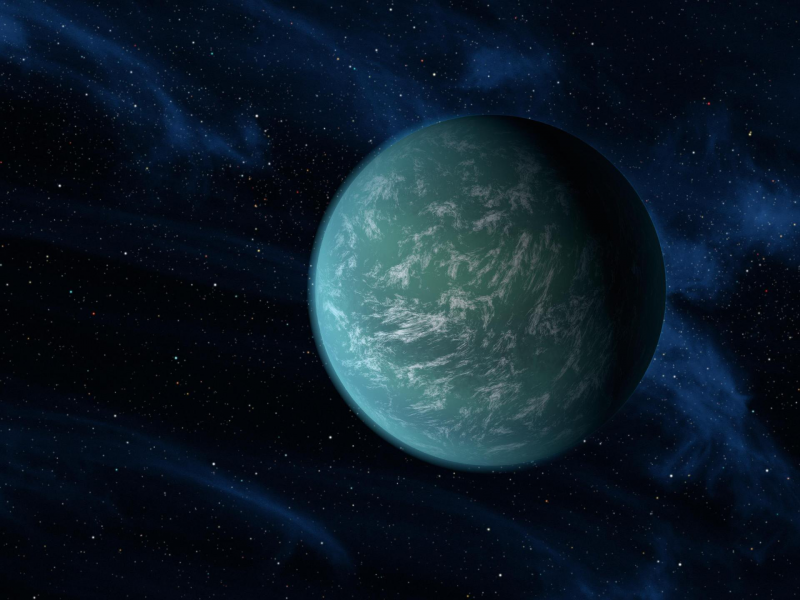

Since Fermi first asked his famous question, space telescopes have searched the stars for Earth-like planets capable of hosting life.

Queloz and his co-winner of the Nobel prize, Michel Mayor, detected the first ever exoplanet (a planet outside our solar system) in 1995. Named 51 Pegasi b, this Jupiter-like planet is located about 50 light-years away in the Pegasus constellation.

Since that discovery, our technology for detecting Earth-like planets has improved significantly.

That's in part why Queloz is convinced that we will inevitably find proof of aliens in the next century, if not sooner. (He suggested that in as little as 20 years we may have the equipment needed to detect extraterrestrial lifeforms.)

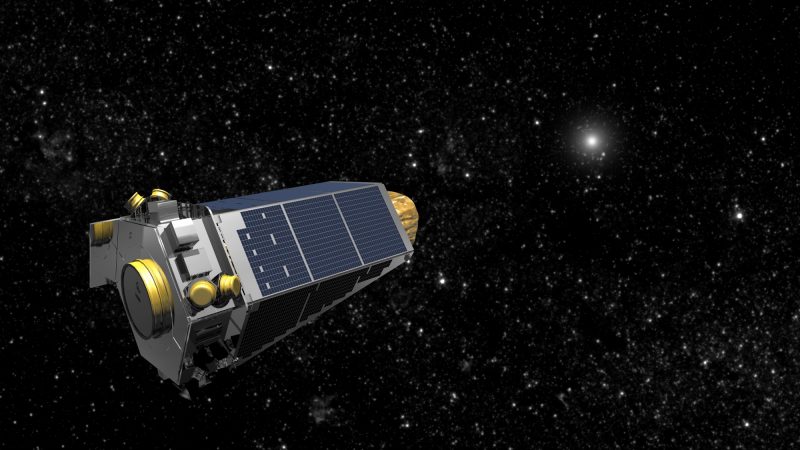

NASA's planet-hunting Kepler Space telescope, which launched in 2009, discovered more than 2,000 exoplanets by the time it was retired in 2018.

Another 2,400 exoplanet candidates are waiting for NASA confirmation.

More than 50 of those exoplanets were deemed potentially habitable, meaning they fall within the "Goldilocks zone" of their respective star - where conditions might enable liquid water to pool on the surface. (Earth and Mars fall within our sun's "just right" zone.)

In 2013 astronomers reported that, based on Kepler data, there could be as up to 40 billion planets comparable in size to Earth that existed within these favorable "Goldilocks zones."

Even if just .01% of those Earth-like planets hosted life, that would still mean 40 million planets out there have life on them.

Another orbiting telescope, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is now scouting the sky for alien worlds. TESS recently found a planet circling a nearby star in the Hydra constellation; the world could support liquid water if it turns out to have a thick atmosphere and be made of rock.

But the chances that our telescopes could be coincidentally pointed at the exact right part of space at the right time to detect signs of extraterrestrial civilization are infinitesimal.

So scientists from the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute point radio telescopes at portions of the sky to collect data. The researchers analyze that information for unusual patterns that might indicate an intentional or accidental transmission from an intelligent civilization.

SETI's monitoring system is predicated on the idea that aliens are trying to message us — we just need to hear it.

But those monitoring efforts have thus far been unsuccessful.

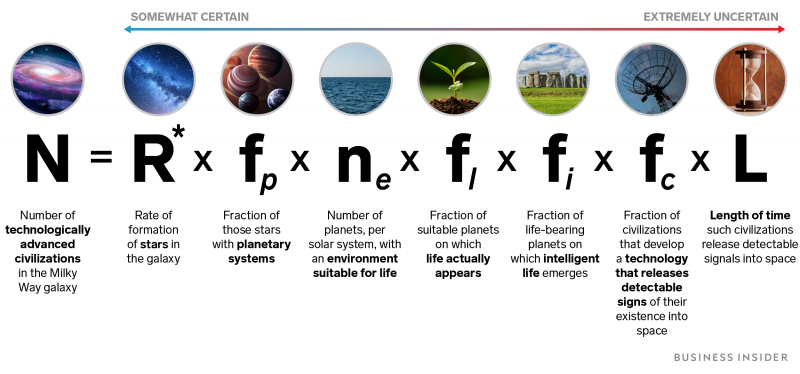

Astrophysicist Frank Drake created an equation in 1961, now known as the Drake Equation, that offers a way to calculate an estimate of number of technologically advanced civilizations in the Milky Way.

The equation is made up of seven variables that, when multiplied together, yield a calculation of the possibility that humanity might someday hear from an intelligent alien civilization (one that has achieved the ability to transmit radio signals that we can detect on Earth).

The problem is that we don't know the value of many of the Drake equation variables with any degree of certainty. Scientists have a good handle on the first three: the rate of star formation, the number of those stars with planets, and the number of those planets within the stars' Goldilocks zone. But the rest are still a mystery.

The first and perhaps simplest answer to the Fermi Paradox is that Earth holds the only intelligent life in the universe.

Astrophysicist Michael Hart explored this question formally in a 1975 paper; he argued that there had been plenty of time for intelligent life to colonize the Milky Way in the 13.8 billion years since the galaxy formed. Since nobody on Earth had heard anything, Hart concluded, there must be no other advanced civilizations in our galaxy.

More recently, a 2018 Oxford University study suggested that there's a roughly two-in-five chance that we're alone in our galaxy and a one-in-three chance that we're alone in the entire cosmos.

But the more astronomers learn about conditions that make a planet suitable for life, the more it seems our galaxy could be much more hospitable to life than previously thought.

Another possibility is that aliens want to talk to us but can't.

SETI assumes that any extraterrestrials we might come into contact with would be more technologically advanced than we are, given the relatively short time humans have existed.

So it's possible that aliens don't use radio waves as a means to communicate. They could be reaching out using a technology that we don't know about yet. Walsh compared the situation to one in which modern-humans would try to chat with a caveman on a cell phone (we're the cavemen in this analogy).

If other intelligent life in the universe has outpaced us technologically, it's possible those beings think Earth isn't worth contacting at all.

Walsh refers to our absence of extraterrestrial contact as "The Great Silence."

One answer to the Fermi Paradox, he says, could be called "The Great Indifference" - perhaps aliens just don't care what a sub-intelligent race has to say.

Or maybe our radio messages just haven't reached anyone yet.

Frank Drake sent out the first deliberate interstellar radio message on November 16, 1974 - 168 seconds of a two-tone sound were beamed toward the star system Messier 13 (or M13) in the Hercules constellation.

Encoded in the message were the atomic numbers of basic Earth elements, the numbers 1 to 10, and a graphic of our solar system to indicate where the message originated from. But M13 is roughly 21,000 light-years away, according to SETI, so Drake's message will take about the same number of years to get there. Then it would take any similar return signal the same amount of time to get back to us.

But not all scientists thought sending messages into space was a good idea. Astrophysicist Stephen Hawking cautioned against attempting to make contact in 2010.

Hawking told the Times of London: "I imagine they might exist in massive ships, having used up all the resources from their home planet. Such advanced aliens would perhaps become nomads, looking to conquer and colonize whatever planets they can reach."

Aliens could also be deliberately hiding from us.

Some researchers have suggested that intelligent life in the galaxy may have the same concerns that Hawking did about making contact, so therefore elect to remain silent.

In "End Times," Walsh puts forward a hypothesis in this vein: Perhaps Earth is being treated like a zoo and humans are a remote group of indigenous galactic dwellers that are being intentionally left undisturbed.

Aliens could simply be content to leave us alone until we become too greedy and pose a threat to the greater universe.

The 1951 Hollywood blockbuster "The Day The Earth Stood Still" explores such a theory. In the film, an alien spaceship lands in Washington, DC to deliver a message: live peacefully or be destroyed as a danger to other planets.

Or perhaps extraterrestrials are just hibernating, Walsh wrote.

The intelligent civilizations we're trying to contact could be in a state of dormancy that may last for billions of years, he said.

Another hypothesis is that we're living in the "galactic sticks," on the outskirts of where intelligent life is located in the Milky Way.

Walsh explores the idea that it may just be hard to reach us way out here, especially if other intelligent civilizations have, like us, not yet figured out an efficient way to travel between star systems.

But that answer to the Fermi Paradox has a problem: The Milky Way is old. Walsh argues that, given enough time, an intelligent civilization should have been able to find us by now, even if they were traveling slowly.

If aliens were traveling at one-tenth the speed of light, it would take them 10 million years to cross the entire Milky Way. That's less than 0.1% of the age of the galaxy.

But perhaps a technologically advanced civilization just can't last long enough to be able to travel through the galaxy for millions of years.

According to this potential answer to the Fermi Paradox, intelligent civilizations could exist in other parts of the Milky Way, but they die out or destroy themselves before they're able to find us or we're able to contact them.

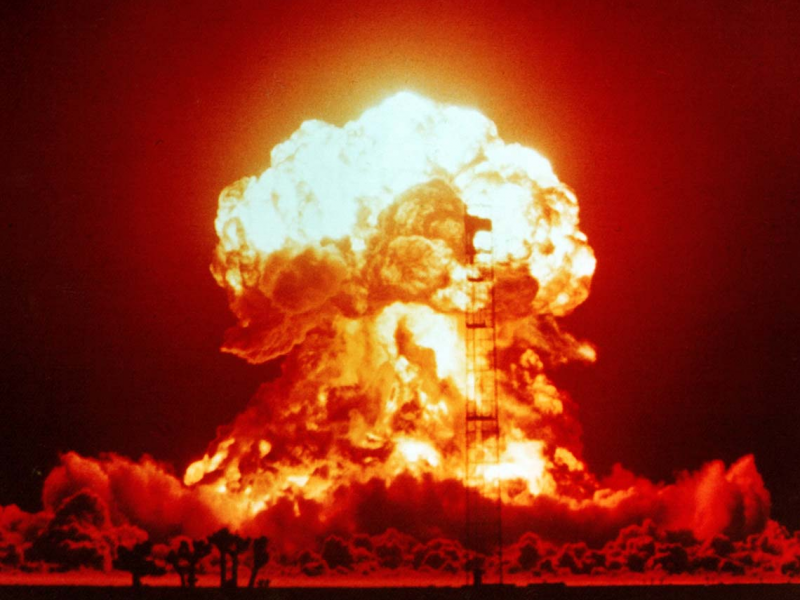

Some scientists have argued that intelligent civilizations similar to ours could have gone extinct because of the same dangers that threaten humanity on Earth.

As philosopher Nick Bostrom has explained, this concept suggests that life on an Earth-like planet has to achieve several "evolutionary transitions or steps" before it can communicate with civilizations in other star systems.

But an obstacle or barrier - a "Great Filter," as it's called in this line of thinking - makes it impossible for an intelligent species to progress through all of those steps before collapsing.

A study published last year points to climate change as the most likely "filter" that prevents a civilization from reaching other star systems.

The study puts forth four scenarios that a civilization could follow as it develops. One of those pathways leads to sustainable existence. But in the other three, civilizations overuse resources and collapse or die off as a result.

So a possible answer to the Fermi Paradox, the study authors posited, is that environmental transformation (whether that involves using up necessary resources or irreversibly changing a climate) inevitably prevents civilizations from surviving long enough to travel to distant stars.

Walsh suggests that we may never find anything in our search for aliens except their remains — evidence of extinct civilizations, in other words.

Walsh calls these clues "necrosignatures." Nuclear holocausts, biological weapons, even disappearing planets leave detectable signs in space, he writes, and humanity should be ready to find and identify them.

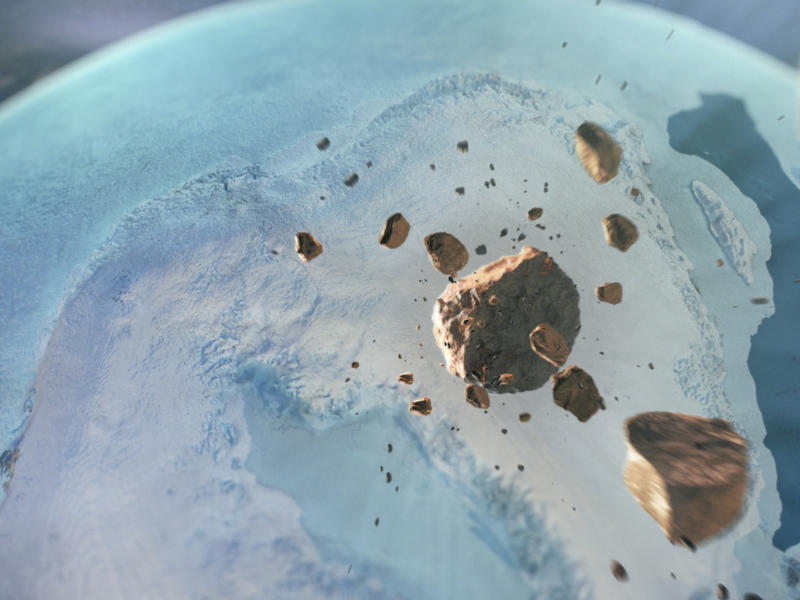

Planetary scientist Alan Stern, meanwhile, thinks it's possible that — unlike humans on Earth — aliens live in the interior of their respective planets, which is why we've yet to find signs of life.

Stern posited that some habitable worlds' liquid water is located under the surface, in the planets' interior. That appears to be the case for Saturn's moon Enceladus.

"If technological civilizations can actually develop in these interior ocean worlds, they would naturally be cut off from us because of the shell of rock and ice above their ocean," he previously told Business Insider. "We wouldn't see their city lights. We wouldn't be able to hear their communication. They wouldn't maybe even know that there was a universe out there to communicate with."

One of the most recent responses to the Fermi Paradox, published last month, suggests that aliens have already visited Earth — just not recently enough for us to have noticed.

The study, published in The Astronomical Journal, posits that intelligent aliens could be taking their time to explore the galaxy, harnessing star systems' movements and orbital shifts to make star-hopping easier.

The study authors suggested that aliens might wait for stars to move closer to one another before spreading across the galaxy, and that other civilizations could have already been here and left no evidence of their visit.

Despite myriad theories as to why we may never make contact, Queloz remains hopeful.

In an interview with the Nobel prize press office, he said that his and Mayor's detection of the first exoplanet almost 25 years ago was merely "the trigger" for humanity's renewed search for other life in the cosmos.

"We are convinced there must be life on other planets, otherwise we wouldn't search for it," he said of his fellow astronomers.