- Japan has one of the world’s toughest asylum policies. Despite having the third-largest economy, last year the nation accepted only 20 refugees.

- Strict policies, geography, and history have limited asylum-seekers’ access to Japan, while a general preference for its homogeneous society means citizens have little motivation to push for change.

- There is no official immigration policy in Japan, which forced much-needed low-skilled labor workers to gain legal residence via the refugee process. The system is overburdened as a result.

- Japan is facing a demographic time bomb. Its rapidly shrinking workforce could easily be boosted by thousands of migrant workers and refugees who are not just willing, but desperate, for work.

Ammunition is one of the best memories Zahir Amini has of his childhood.

“I enjoyed playing with bullets,” laughs Amini. “It was a popular toy when I was a kid.”

Born in Afghanistan, Amini grew up surrounded by shell casings and abandoned weapons that littered the streets after a decade-long Soviet Union occupation ended in 1989. A reprieve was supposed to follow, but instead civil war erupted.

The Taliban gained control and soon began persecuting ethnic minorities, including Amini and his family.

"It was dangerous at times, very dangerous. I saw lots of my friends die, stepping on mines and things like that," he told Business Insider.

Amini, who requested his name be changed to protect his safety and that of his family, was under 10 years old when his family fled across the border to seek refuge in Pakistan. But life was nothing like what the Amini family had imagined.

Once in Pakistan, the family's ethnic group, the Hazaras, were an even smaller minority, and they felt more targeted than ever. While some Pakistanis left to become Taliban fighters, many more - including police - dealt out abuse, discrimination, and death threats.

"They would write on the walls of the building and the houses, 'You people are infidels.' Which is a sign of threat, that we will kill you in time," Amini recalled.

His family spent a decade in Pakistan, moving frequently, while Amini's father was in Japan. After entering the country on business, the situation in Afghanistan changed and he applied for asylum. He spent the following years fighting to be recognized as a refugee.

Finally, in the late 2000s, he was granted a visa and the Amini family emigrated the following year.

The government provided little help and with no financial support, no language lessons, and just Amini's father working, the family struggled for years.

They were one of the lucky ones.

Refugees need not apply

Japan has the third-largest economy on the planet, but in the last five years, has granted refugee status to fewer than 100 people.

In 2013, just six applications were approved. Eleven people made the cut the following year, followed by 27 in 2015. Out of the 10,901 people who applied in 2016, just 28 were granted refugee status in Japan. The number of applications jumped to more than 19,000 the next year. Only 20 were accepted.

While headlines around the world have slammed these numbers, they are actually misleading Dirk Hebecker, head of the Tokyo branch of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), told Business Insider. Last year's 20 approvals didn't come from the 19,000-odd applications, but were people who had applied years earlier, a byproduct of the slow-moving vetting process.

"Excuse my blunt reaction on this, but it's very stupid to put these two figures together. It's well-known how long it takes in Japan and many other countries to actually have a result," Hebecker said, referring to the process of seeking asylum.

But despite a lack of correlation, the raw numbers tell a hard truth: Japan is one of the world's least-welcoming countries for refugees.

Estimates given to Business Insider indicate there should be dozens, if not hundreds - or even thousands - more refugees being granted protection by Japan every year. And the reasons this doesn't happen are complex and multiple.

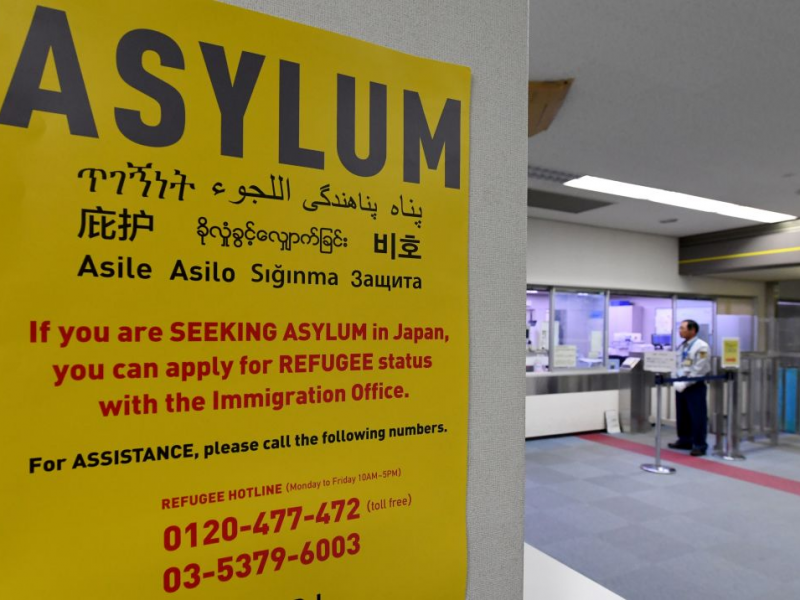

Japan, a geographically remote country, requires that refugee applications be submitted in person. But many modern-day refugees come from the Middle East and Africa, which pose large logistical and financial hurdles for asylum seekers.

For those who do make it to Japan, they must already have some sort of visa, otherwise they'll be detained and barred from seeking refugee status. But getting one of those visas is incredibly difficult.

Take Amini's previous residences, for example. Japan doesn't offer a tourist visa if you're traveling from Afghanistan. Applicants who aren't diplomats must be invited into the country by the UN or a select number of Japanese organizations. In Pakistan, potential tourists must supply bank statements, a letter from the bank manager, evidence that they are employed, passports, and identity cards.

But asylum-seekers rarely have these documents.

"When refugees have to leave their countries, a lot of them try to throw away all of their documents, especially when it comes to their identifications or being part of a political party, things that show who they are, what they did, what their family stands for, their ideologies, and their background," said Amini, whose family escaped with enough money for two or three weeks, some fruit, the clothes on their backs, and no documents.

"We had to burn everything. We had to burn our identity cards, even though our facial features tells everything of who we are, our ethnic group, but still we couldn't carry any document with us," he said.

Amini believes this is a reason why Japan approves so few applications. Hebecker, the head of the Tokyo UNHCR office, agrees that this is one of the system's biggest bottlenecks. So much so, the agency is currently working with the Ministry of Justice to address this by increasing the department's capacity to research claims in home countries and in other languages.

But key to Japan's policy is its focus instead on UNHCR donations - it is the fourth-largest government donor. The country also employs a unique definition of a refugee.

Despite signing onto the 1951 Refugee Convention, Japan only recognizes refugees who are individually targeted and persecuted, regardless of whether they belong to a persecuted minority, or are fleeing war or conflict.

Saburo Takizawa, who previously held Hebecker's role and is now the chairman of the nonprofit Japan for UNHCR, told Business Insider it's a definition that excludes most modern refugees, abiding "by the letter, if not spirit," of the convention.

"What the government is doing is very much abusive of the human-rights convention," Amini said.

And there's little popular push to change this. Though the experts who spoke with Business Insider were divided on how open citizens are to refugees - as are various polls - they all agreed that Japan is a homogeneous country and, generally, people would like for it to stay that way.

"When it comes to the government stance, I think they've been excessively obsessed with the preservation of this homogeneous society," Amini said.

This preference, according to Takizawa, could have historic roots in the Edo period. For more than 200 years, Japan thrived under isolationist policies that saw foreigners expelled and foreign contact forbidden until 1853.

More recently, fear and anxiety began to take hold in the 1980s when Japan agreed to take 10,000 Vietnamese "boat people" who were landing on the country's shores almost daily. And now those fears have risen again as the country turns its eye toward North Korea.

A "flood" of North Korean refugees

There's a persistent fear in Japan that adopting a more liberal refugee program could be the first step to one day being forced to accept a large-scale influx of refugees fleeing North Korea.

And the country's leaders and media haven't helped.

Editorials have warned that there could be a dangerous "flood" of North Korean refugees; that armed North Koreans might disguise themselves as refugees and target military bases or nuclear power plants; and that North Koreans have a penchant for bribery, stimulant drugs, and a lack of civil interactions that could "create turmoil" in society.

In September last year, Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aso even asked whether defense forces should shoot North Korean refugees if they landed on the country's shores.

"We'd better think about it seriously," he said.

Aso also cited a potential 100,000 North Korean refugees seeking residence in Japan, a calculation based on the likely descendants of 6,000 or so Japanese women who migrated with their North Korean husbands in the second half of the 20th century. But Takizawa puts the number closer to a few thousand.

Adding to the complex nature of this discussion is the enmity between the two countries. While North Korea abducted a number of Japanese citizens in the past, it also indoctrinates its people to hate Japan as much as the US and South Korea. Aside from that, the logistics don't work. There simply aren't enough ships to carry 100,000 refugees from North Korea and, in the case of war, fuel is likely to be in short supply.

The 620-mile (1,000 kilometer) high-sea journey is also incredibly treacherous. Fishing boats, known as ghost ships, semi-regularly wash ashore in Japan, with the remains of deceased North Koreans on board. Only three boats of North Korean refugees have ever successfully made it to Japan.

Takizawa called the deputy prime minister's estimate an "illusion."

"But it does have a political impact and I believe it is why the current government won last year's election - the fear of North Koreans coming to Japan in hundreds, thousands," he said.

Applications from conflict-free countries are skyrocketing

Japan's geography, history, and social climate may explain why it has one of the toughest refugee policies in the world, yet applications have been skyrocketing.

In 2010, Japan received 1,202 refugee applications. By 2017, that increased 1,600% to 19,628, nearly as many as were processed in the more than three decades leading up to 2014.

"The government has been taken by surprise, and we are all surprised. When I was at UNHCR the number of asylum-seekers was 800 or 900 and I thought this was a big increase," Takizawa said.

The other anomaly is the applicants' nationalities.

In 2017, Southeast Asia - namely the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Sri Lanka - topped the list, despite not typically being a refugee-producing region.

Filipinos accounted for a quarter of the applicants. Conflict zones in the Middle East and Africa - Syria, Afghanistan, Congo, Iraq, Yemen, and South Sudan are some of the usual countries UNHCR expects to see - accounted for only 1%.

Foto: source TOSHIFUMI KITAMURA/AFP/Getty Images

Foto: source TOSHIFUMI KITAMURA/AFP/Getty Images

The Ministry of Justice has previously said, and every expert Business Insider spoke to agreed, the vast majority of applicants in recent years are economic migrants using the refugee pathway to gain a work visa, and overburdening the system in the process.

Southeast Asian applicants soared after 2010 when, under pressure to provide more resources to asylum-seekers whose applications can take years to process, the government began offering work visas for any asylum-seeker who has been waiting at least six months.

In a country without any formal immigration policy and lacking a low-skilled migrant visa to fill hard-labor jobs, the refugee system provided the perfect route to a steady income, and some employers even encourage new arrivals to apply for asylum to get a lucrative work visa.

For southeast Asian applicants, getting to Japan to file paperwork is also easier. Conditions for Filipinos to be granted a visa have been relaxed, while visitors from Thailand don't require a visa at all.

"As long as you say, 'I'm a refugee,' all they need to do is just wait six months and then they can start working, and there are no restrictions, they can work anyplace, any period," Takizawa said.

One of the clearest indicators that the applications aren't legitimate is their confinement to Japan.

"If so many Indonesians seek asylum in Japan why are not similar numbers seeking asylum in Korea? And that's not the case. If you look at Korea's numbers, they're really different. So I think it's pretty obvious that there are many people who very consciously use the institution of asylum in Japan to pursue other aims," Hebecker said, adding that the pattern holds true in other industrialized nations.

There are also few Southeast Asian people in Japan's detention centers, meaning they nearly all arrived on valid visas, says Alex Easley, an American expatriate who volunteers with refugees and immigration centers.

"A lot come with work permits to work in construction or hotel jobs. But they're treated sometimes like slaves and the money is low so they figure the best thing to do is file for refugee status and then they can get a work permit and get a better-paying job," Easley told Business Insider.

And those conditions aren't an exaggeration.

The US State Department has identified Japan's Technical Intern Training Program (TITP) - which allows people from developing countries to learn skills in manufacturing, construction, agriculture, and health care for up to five years, and is the closest thing Japan has to a low-skilled visa - as facilitating numerous human-rights violations. In its most recent annual report the department said TITP has "effectively become a guest worker program."

While some interns aren't taught any skills, others experience forced labor conditions including having their passports confiscated, being given arbitrary salary deductions, being confined to particular accommodations, being prevented from communicating with anyone beyond their colleagues, with some paying up to $10,000 to participate in the program.

There are 230,000 people currently in the program and the government identified an increasing number of people, particularly from the Philippines and Vietnam, applying for refugee status when their trainee program was coming to an end.

To Takizawa, the trainee program is just a way to import cheap labor while maintaining that Japan doesn't have an immigration policy. And the refugee system suffers as a result.

"This asylum-seeker policy is a victim of Japan's migration policy. If you try to fix the asylum system by itself it wouldn't work, we must fix it and the global migration policy," Takizawa said. "The government says we don't accept migrants but we'll accept them as casual laborers, we'll accept them as students, we'll accept them as technical trainees, and the government allows them to work."

But there's nothing illegal about swapping from a trainee visa to that of an asylum-seeker's. And as an asylum-seeker, people have far more flexibility and freedom, able to earn two to three times more than they did as a trainee, and magnitudes more than they ever could back home.

"I know some people that have been waiting for 20 years and they haven't been put back inside so they're just waiting, so long as they can stay in Japan and work," said Easley, the American expatriate who at one point was hosting 16 asylum-seekers in his one-bedroom flat. "They know there's no possibility to get [refugee status] - 20,000 people applied last year there's no chance of getting it, they're not even thinking about that - they just want to be able to stay and work."

Foto: Refugees cross a wooden bridge at the Mae La refugee camp, located near the Thai-Myanmar border. source CHRISTOPHE ARCHAMBAULT/AFP/Getty Images

Foto: Refugees cross a wooden bridge at the Mae La refugee camp, located near the Thai-Myanmar border. source CHRISTOPHE ARCHAMBAULT/AFP/Getty Images

There could be dozens, hundreds, maybe thousands of refugees

So if Japan were to unburden its processing system, how many legitimate refugees should the country be approving?

There's little consensus on the matter, with each person Business Insider spoke to giving vastly different estimates.

Amini believes the number of people who escaped war and persecution could be as high as 2,000, but Takizawa zeroes in on the 200 to 300 applicants from the Middle East and Africa who apply each year. If the refugee definition were relaxed, he believes 50, maybe even 100, could be considered refugees.

But the Japan Association for Refugees (JAR), a leading nonprofit that provides legal and social services to asylum-seekers, says on its website that, lawyers estimate that "the number of applications that should be accepted is in hundreds."

JAR also points out that a not-insignificant number of applicants, who were rejected by the Ministry of Justice, end up getting approval, which "proves that the system is not working properly."

But many simply don't want to move to Japan

While economic migrants are desperate to live and work in Japan, experts told Business Insider it's not a desirable country for legitimate refugees, and some end up in Japan almost by accident.

"The number of refugees who wish to come to Japan is very small," Takizawa said. "Many of them want to go to Canada, or France, but there are no direct ways there, there are no refugees visas, so some of them come to Japan and then attempt to take another flight to, say, Canada. And then they are not allowed to enter so they ended up staying in Japan."

Other times, refugees have turned down opportunities to relocate.

In 2010, Japan launched a pilot refugee resettlement project with UNHCR to accept 30 Karen refugees a year from camps in Thailand, but the response was underwhelming.

"It was difficult to interest refugees to come to Japan. They were used to the resettlement call for the US and Canada, maybe Scandinavian countries are more well-known. But refugees are very careful when they decide. Because we don't just ship them around," Hebecker said.

Some of the barriers include the need to learn a new language, a six-to-nine-month mandatory orientation course, and a high cost of living that requires both parents to work. Past research by Australia's parliament has also found that asylum-seekers who have a choice weigh up social networks, historical ties between the new country and their home, simple travel, and a common language.

"And Japan lacks all of them," Takizawa said.

Amini has now been in Japan for a number of years, and despite being multilingual and passing the top level of language proficiency, he still feels like he has a "language problem" with Japanese.

He sees Japan as a "beautiful country, a peaceful country," one full of opportunity and convenience, where education and transport work with ease, but the government does little to help the hundreds of people it grants humanitarian visas, rather than refugee visas, every year.

"It's a homogeneous country. I felt my family and I were treated as different people. But that's fine. What was very much shocking to me was we had very little means of surviving in Japan," Amini recalled. "The Japanese government didn't provide us with some sort of assistance to survive."

Amini's siblings were sent to local Japanese schools where they couldn't understand their classes, while he, having just graduated high school, had no funds to pay to learn Japanese or go to university. The family struggled for years.

"Daily life was tough," Amini said. "It was, for me, too difficult. I was having a mental breakdown. Seeing my dad working from morning to evening, all day until late at night, but still he wouldn't be able to meet the expenses we had as a family. It was heartbreaking."

Eventually, Amini received a scholarship to attend the English program at a Japanese university, and he finally felt like he found his place in his adopted country.

Migration could address Japan's demographic time bomb

It makes little sense for Japan to reject immigrants who want to work.

Japan is facing a demographic time bomb as its society rapidly ages and the population shrinks. More than a quarter of Japanese people are aged 65 or older while 2017 saw the country's lowest number of births in nearly 120 years.

While Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has promoted getting more women into the labor force and encouraged the elderly to work longer, talk of labor migration to boost the working population has barely risen above a whisper.

And with a lack of pressure from constituents, the government has little incentive to change anything. The country maintains its stance of no official immigration policy, its trainee program fills low-skilled labor needs, and changing either element of the status quo could lead back to a labor shortage.

"If people get refugee status they usually get a visa and can find the kind of work they want to do and not do the dirty jobs. If you give too many people visas, who's going to do the dirty work?" Alex, the American expatriate, said. "I think the Japanese, I can't say for sure but my feeling is, they need those people to be doing those jobs."

According to Alex, many people who arrive in Japan without a visa won't be able to apply for refugee status, but the government doesn't go to great lengths to prevent them from working. He says people in detention just need to wait seven or eight months and, if they have a guarantor and pay a bond of $930 to $2,800 (100,000 to 300,000 yen), they can be released despite having no work permit.

"They usually come out and everybody works. They usually do jobs the Japanese don't want to do. Low pay and dangerous jobs. But actually, the money isn't that low. It's maybe $10 an hour, which is normal for part-time work in Japan. Most of the time, it's separating trash or recycling, and people are happy for the work," Alex said.

But other arms of the government have slowly begun cracking down on foreigners who don't have visas. More than 300 arrests were made as a result late last year.

"It's like a cat-and-mouse game," Alex said.

In the Land of the Rising Sun, change may be on the horizon

In January, Japan began prioritizing refugee applications by people who are most likely to be deemed legitimate, and work visas have been restricted to only those applicants.

Those whose claims don't meet Japan's strict definition, or who have re-submitted a claim, will not only be denied a work visa, but could also face detention and even deportation.

Within the first few weeks, applications had dropped by 50% from the same time last year, "indicating that the main motive of applications is the work permits," according to Takizawa.

This means companies could soon lose access to thousands of potential laborers.

"Fixing of the asylum system cannot be the only answer because its just a painkiller; it doesn't cure the symptoms," Hebecker, the head of the UNHCR's Tokyo office, said.

Takizawa, who was once the financial controller of UNHCR in Geneva, believes Japan's most important global contribution is actually its monetary donations. But he would also like to see Japan offer work visas for refugees in camps around the world, similar to the new Syrian student program, but that's likely a long way off.

In the meantime, Abe has instructed his ministries to design a system where Japan can accept foreign laborers, without their family members, for a fixed period of time. The sort of visa that could be very useful in preparing for the 2020 Tokyo Games. They are set to return with their plans mid-year.

The Karen-refugee pilot was eventually expanded and Japan now has a second resettlement program. Over five years, up to 150 Syrian refugees will be able to study in graduate-degree programs, and bring their families for resettlement, to Japan.

"This is a step in the right direction. The numbers are so small but the government is opening new channels of accepting refugees," Takizawa said, "and I'm seeing this as a small but important step forward."

For Amini, the future is uncertain.

"I left Afghanistan when I was very little. So going back to a country that I went through lots of traumatic things, traumatic experiences, it's a nightmare. I can't," he said, trailing off.

"I'm working my best to get a job in Japan to stay here. But I don't know what's going to happen next."