Tony Duffy/Getty Images

- Men's gymnastics doesn't reward the kind of beauty and artistry that has been viewed as the domain of women's gymnastics.

- In recent decades, gymnasts have been expected to perform their genders via skill selection and movement vocabulary.

- What feats of artistry might the men be capable of if dancing and leaps were rewarded?

- See more stories on Insider's business page.

A few weeks ago, Australian elite gymnast Heath Thorpe posted a video of himself performing a switch leap with a half turn.

Gymnasts frequently upload to social media snippets of routines they're working on in training. What made this unusual was that the skill is seen in women's floor routines – never in men's gymnastics.

i like this. pic.twitter.com/dvyLUv6TLd

— Heath Thorpe (@thorpeheath) July 14, 2021

Thorpe executed it beautifully. Swinging his extended right leg to the front, he initiated the half turn and extended into a full split, perhaps even a bit beyond. He landed in a kneeling posture on the mat, chin up, with his left arm extended in front of him.

Underneath the video, the replies were effusive. Giulia Steingruber, a Swiss elite gymnast and Olympic medalist, asked Thorpe if he would mind loaning her some of his flexibility for the next few weeks as she competes in Tokyo. Others suggested that he submit the skill for valuation so he can get rewarded for it in a future competition. One person even suggested that his leap was so good, it was on par with those of the rhythmic gymnasts, whose leaps are exceptional and completely overspit.

As to why he posted the video to Twitter, Thorpe wrote: "I was proud of it. It is as simple as that."

And it should be just that simple. But as some of the more wistful responses indicated, men's gymnastics doesn't reward the kind of beauty and artistry that Thorpe had demonstrated in that brief clip.

Previously when Thorpe posted videos like this one, the response, while mostly positive, came largely from fans of women's artistic gymnastics (WAG). What struck him this time was the cohort responding. "I had international MAG [men's artistic gymnastics] athletes, FIG [International Gymnastics Federation] judges from Australia and other countries; even non-gym fans showed support," he said.

The problem is that the leaps that Thorpe wants to perform aren't even listed in the Code of Points for men's gymnastics on floor exercise. In a points-based sport like gymnastics, where athletes try to rack up as many of those as possible, this means that a male gymnast who performs leaps will receive no credit for doing so.

Perhaps there aren't a lot of male gymnasts who wish to do leaps and turns in their routines; I haven't surveyed everyone so I have no way of knowing. But Thorpe certainly wants to do them and I doubt that he's the only one. But the fact that an entire category of floor movement is simply absent from the rulebook is not a simple oversight. It speaks to the fraught relationships that men's gymnastics has with being associated with women's gymnastics and femininity.

This is why, until about a year ago, Thorpe was reluctant to share these kinds of skills. "I used to always hesitate to post certain things, including leaps. But as I have grown into my identity, I have lost that concern of what people think," Thorpe, who is openly gay, said in an interview.

An eternal 'catch-up'

From almost the very beginning, men's and women's gymnastics have effectively been different sports.The modern version of men's gymnastics emerged in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and its initial purpose was to prepare men for soldiering. In Degrees of Difficulty: How Women's Gymnastics Rose to Prominence and Fell from Grace, Dr. Georgia Cervin writes that Johann Gutsmuth, the "grandfather of gymnastics," wanted the sport to "counteract "effeminate education."

"From the outset it aimed to promote masculinity," she wrote.

Women's gymnastics was created later and with a very different agenda - to teach elegance, flexibility, and good posture, and thus prepare women for their roles as wives and mothers. This is one of the reasons why it was allowed into the Olympic pantheon in 1928 with little resistance from sporting officials. The IOC vastly preferred this "feminine appropriate" sport to the women's track and field events they also added in 1928. The IAAF [International Association of Athletic Federations] and the IOC allowed a select few track and field events for women into the Games due to the success of Alice Milliat's Women's World Games, which was attended by 20,000 people, featured track and field events for women, threatened the IOC's monopoly over global sport. The IOC and other international federations didn't want to encourage women to display qualities that they had marked as "masculine," such as speed, strength, and aggression. The early version of women's gymnastics didn't highlight any of those qualities.

"Institutions like the FIG and the IOC were crucial to normalizing hierarchies of social difference between men and women, preventing them from competing together and demanding that women use shorter distances, reduced time, and modified equipment," Cervin writes.

Though in the early years, the apparatuses were in a bit of flux for the women - they dabbled in parallel bars and the flying rings for a spell - when the sport settled into its current form in 1952, the women were left with four events for them to the men's six. And two of the women's apparatuses were quite dancey - the floor exercise and the balance beam. In early versions of the women's Code of Points, phrases such as "harmonious flexibility and feminine grace" appeared, Cervin observes. "Creating these differences in expectations between genders ensured both that women gymnasts posed no threat to masculinity in the sport and that gender ideals remained firmly separated."

Looking back across gymnastics history, it's not possible to consider male and female gymnasts side by side since there is only minimal overlap in terms of equipment and movement styles. This is the reason why I sometimes vacillate between calling Simone Biles the "greatest female gymnast of all-time" and dropping the gender qualifier altogether. I don't know how Biles would be at rings or pommel horse because she doesn't train or compete on those events, and I don't know how good Kohei Uchimura, the greatest male gymnast of all-time, would be on the balance beam. (That said, there is this old clip of Biles messing around on a mushroom, which is a training aid for men's pommel horse, and she isn't too shabby.)

Tim Clayton/Corbis via Getty Images

This arrangement ensured that gymnasts like Biles can't prove themselves against the men in terms of ability and athleticism.

Interestingly, while men and women gymnasts never competed against one another, that did happen in the early years of competitive figure skating, until patriarchal interference split the sport in two. In fact, in 1902, Madge Syers took second at the world figure skating championships, behind groundbreaking Swedish skater, Ulrich Salchow. Shortly thereafter, the International Skating Union closed the loophole that allowed Syers to enter the competition. In 1905, they created a new category, just for women. "Gendered sports categories are not natural or inevitable," Mary Louise Adams writes in Artistic Impressions: Figure Skating, Masculinity, and the Limits of Sport.

This interference is even more obvious in gymnastics given that the men's and women's sports have different events with different physical requirements. Women compete in vault, uneven bars, balance beam and floor exercise, while men have the floor exercise, pommel horse, still rings, vault, parallel bars and horizontal bar.

Tom Pennington/Getty Images

Even on an apparatus like floor exercise, where there is overlap, there are different distinct demands for men and women, which also hinders cross-comparison. Biles has proven herself the equal to men when it comes to tumbling, but must also add dance and leaps on top of the acrobatic requirements. And what about the female gymnasts who aren't Biles? "On floor maybe women could do much harder if they didn't have to dance around all the time," Cervin said in an interview.

The reverse is also true: what feats of artistry might the men be capable of if dancing and leaps were rewarded? "Maybe men would be awesome [at] beam, but we don't know, because they're never been asked to demonstrate flexibility," she added. (Some men might do a split on floor exercise, but that's the extent of it when it comes to flexibility.)

As women's gymnastics evolved from being seen as a "feminine appropriate" sport, the Code of Points adopted more and more acrobatic elements from the men (though they get a new name when they're performed for the first time by a woman). There are notable exceptions, such as the Yurchenko, the ubiquitous roundoff-back handspring entry vault that both men and women do, which was first done in competition by Soviet gymnast Natalia Yurchenko in 1982. (The vault only really took off on the men's side after 2000 when the new vaulting table was introduced. Previously, the men competed on the long horse, which was narrow, and made a backward entry vault quite perilous.)

And so, for the most part, men's gymnastics doesn't look to the women for guidance or ideas, while women's gymnastics has elements of artistry that some men might excel at, if given the opportunity.

A 'macho' imperative

When I interviewed male gymnasts for a story about the slow decline of men's college gymnastics, they spoke of being mercilessly mocked by their non-gymnast peers when they were younger for doing a sport that many associated with women and girls.

Thorpe remembers this well. "Growing up as a gymnast, I was often met with people who were not involved in the sport calling it 'gay' or 'for girls,'" he recalled. "However, the reality is men's gymnastics is actually very hyper-masculine."

The fact that the sport is sometimes dismissed as "gay" complicate things for queer athletes. "When I realized I was gay, I told myself that I would never come out while I was still in the sport," Thorpe said. "That had nothing to do with a fear of not being accepted by my family or friends, but instead was driven by the fear of perpetuating a stereotype of gymnasts being gay."

2016 Olympic silver medalist Danell Leyva said that the stereotypes made it more difficult to come out as bi/pansexual, and he only did so after his career was over." [The stereotypes were] such a big factor in it...Just not giving the people the satisfaction of being right because it doesn't come from a good place," he told the Olympic Channel.

"I had a ton of teammates come out after they graduated or much later into their careers because they didn't feel like they could come out before," Jason Shen, a former Stanford gymnast, told me.

Ivan Romano/Getty Images

Men's figure skating, which has a similar public perception, also struggled to acknowledge its queer athletes. In 2009, in an effort to macho up the sport's image, Canadian figure skating created - and then quickly abandoned - an ad campaign that many decried as homophobic. The campaign "aimed to rebrand the sport by getting skaters to emphasize the difficulty and danger of their stunts - and, in one case, to pose for photos on Harley-Davidsons," Blair Braverman wrote in 2014.

"Coaches and athletes would often use being fem or gay as an insult to myself and other athletes, and when coming to terms with your identity as a kid, that really damages you," Thorpe said. He acknowledged that while there's been progress on the inclusivity front, there's still more work to be done.

The fear of being associated with the "feminine" has even filtered into things like skill selection. "Even up until the last year or so, I had steered clear of skills that were more common in WAG [women's artistic gymnastics] out of fear," Thorpe said. "That was really hard for me, because I really look up to so many female gymnasts as role models for myself. I love bringing that admiration and putting it into my own gymnastics." The skills that appealed to Thorpe were ones that required greater flexibility and range of motion, which he clearly has in spades if his gorgeous leap is any indication. "Whenever I would suggest such skills, I was met with being told something similar to 'go join women's gymnastics if you want to do that.'"

The implication, for gymnasts like Thorpe, was that influence in sports should be unidirectional - from men to women, and not the other way around. The women are supposed to be eternally playing catch-up to the men, not inspiring them.

An unexpected outgrowth of this way of thinking is that elite gymnastics doesn't have the same anxiety about men masquerading as women in order to "infiltrate" women's gymnastics. This greatly differs how the matter was treated at other international sports federations where it was something of an obsession, such as for track and field. "There was no question what gender or what sex someone was because the gender performance is so built into the sport," Cervin said. ""Oh, you look like a woman. You're dancing like a woman.'"

The remarks that Thorpe heard growing up that some of his skills belonged in women's gymnastics was a response to the fact that male and female gymnasts weren't simply performing skills; they were performing their genders via skill selection and movement vocabulary.

With that in mind, skill choice becomes far more fraught. While it is still mostly about doing the most difficult routine you can possibly do and building your start value (or difficulty score) as high as it can go so you maximize your chances of getting a high score, it is also subtly about proving your masculinity and showing how you're distinct from the women.

On the high bar, Thorpe performs a Markelov, which is a skill that originated on men's high bar, but is now far more common on women's uneven bars. (Russian gymnastics legend Svetlana Khorkina used the skill through her decade of near-dominance on that event.) On vault, he does a Shewfelt, which is a two-and-a-half twisting Yurchenko named for 2004 Olympic floor gold medalist Kyle Shewfelt. This skill is far more common in women's gymnastics, where it's called the Amanar for Romanian great Simona Amanar. (They both introduced it at the 2000 Olympics.) In terms of tumbling, Thorpe's floor is fairly straightforward when it comes to tumbling, he's been working on incorporating more artistry, like the leap he showed off in the video.

'Nothing but tumbling'

Leaps aside, some of what Thorpe is doing marks a return to an earlier era of men's gymnastics. If you look at footage of male gymnasts in the 70s, you'd see a very different style of floor performance. (And also, suspenders!) It was much more fluid, moving from tumbling to dance elements and then back to the acrobatics.

This is Toby Towson, a former American gymnast who would go onto become a dancer, coach, and choreographer after his athletic career was over. (He originated the role of Barkley the dog on Sesame Street.)

The movements between the tumbling elements were fluid and graceful; like Thorpe, Towson demonstrates flexibility, extension, and an exceptional toe point. Towson may have been singular in his movement quality but the routine itself was not that unusual for that era.

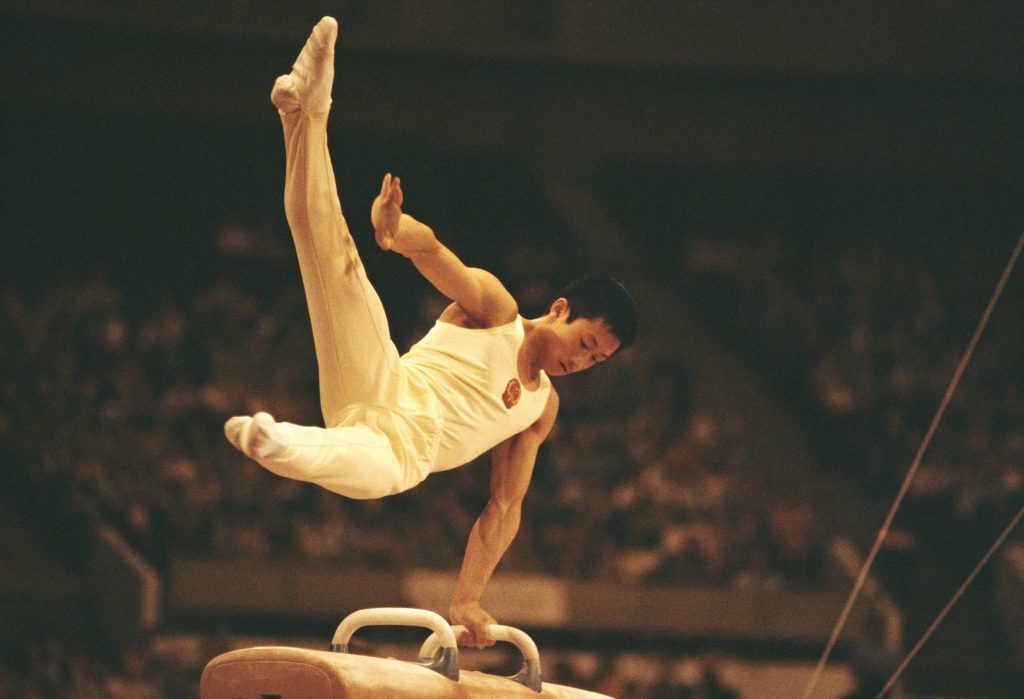

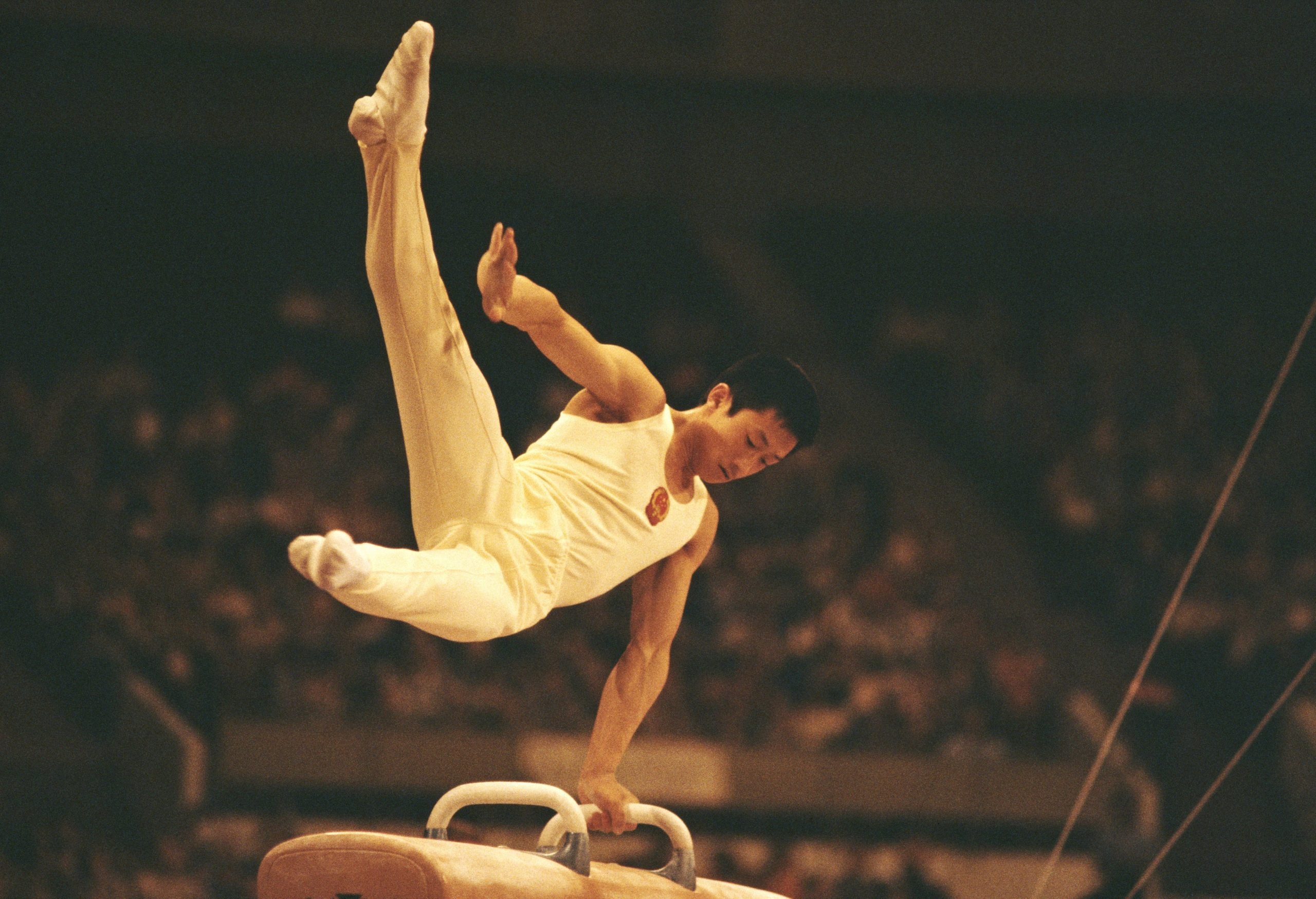

And here's Tong Fei performing in 1983. He originated the "butterfly" on men's floor, a non-acrobatic skill that remains in the Code.

There was a good amount of style in men's floor exercise, even into the early aughts when the difficulty in tumbling had already increased quite significantly. In 2004, Canadian Kyle Shewfelt won the Olympic gold medal with a routine that showed off his exceptional lines and toe point (in addition to his excellent tumbling).

Compare those exercises to the gold medal winning routine of Artem Dolgopyat earlier this week in Tokyo, whose routine was tumbling-only, with the exception of the one required non-acrobatic movement. His routine is not an anomaly.

Towson told me that it's difficult for him to watch men's floor exercise in the present. "I just get sad and depressed because the rules have changed," he said. "It's very, very different than [how] it used to be. It used to be a combination of balance, tumbling, grace, [and] flexibility...The new rules force these guys to just tumble."

The leaps that Thorpe wants to perform aren't even listed in the table of "non-acrobatic elements" on floor exercise, meaning a gymnast who performs them won't receive any scoring bonus for doing them. The skills that are listed tend to emphasize strength, like a planche, or balance or both. A gymnast is only required to do one of these elements in their routine. And since most aren't highly valued, so it's not really worthwhile to do more than the bare minimum there, especially when you have just 70 seconds to cram in as much hard tumbling as possible.

Right now, Thorpe is working on incorporating leaps simply out of a desire to do them and the pleasure it brings him (and others). "This year, I incorporated a sissone into my routine, which is only really performed in women's gymnastics. I got so much joy from doing it," he said. (A sissone is a split jump that takes off from two feet but lands on just one. They are ubiquitous in women's floor exercise and balance beam.) "Enjoying myself is more important than results and I have actually learnt that the reality is, the more I am loving what I do, the better I perform."

But the fix isn't just adding leaps and jumps back into the Code. It will require a major shift in perspective.

"We need to stop seeing queer gymnasts as a threat to our sport. We need to stop seeing women's gymnastics as 'easier' or 'less than,'" Thorpe said. Anyone who has tried to do the elements in the women's rulebook can attest to the fact that they are not easy, whether done on the floor or beam. A male gymnast performing any of these skills wouldn't be watering down his exercise; he'd be challenging himself in a new way.

"Leaps are for everyone," Thorpe said.

***

Dvora Meyers is a freelance journalist based in Brooklyn. She is the author of The End of the Perfect 10: The Making and Breaking of Gymnastics' Top Score from Nadia to Now and publishes a gymnastics newsletter at Unorthodox Gymnastics.