- Today, Iowa Democrats will be the first in the country to express their choice for the Democratic presidential nominee.

- While Sen. Bernie Sanders holds a narrow lead over the rest of the field in Iowa, most recent polls of the state show the leading four candidates bunched closely together.

- Since 1972, Iowa has historically played an important role in narrowing the size of the field and determining which candidates are viable going forward.

- But with an unusually large Democratic presidential field, Iowa may be less relevant this year than ever. Candidates are spending more time in other states, and have even criticized Iowa for being unrepresentative of the party.

- Here’s what you need to know about the difference between primaries and caucuses, how the Iowa caucus works, and why it may be less relevant this year than ever before.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Today, February 3, Iowa Democrats will gather across the state to express their choice for the Democratic presidential nominee and allocate delegates to the Democratic National Convention in July.

For Democratic voters and activists, the Iowa caucuses represent the moment they begin possibly removing President Donald Trump from office, something they’ve been waiting to do since the day after his election in 2016.

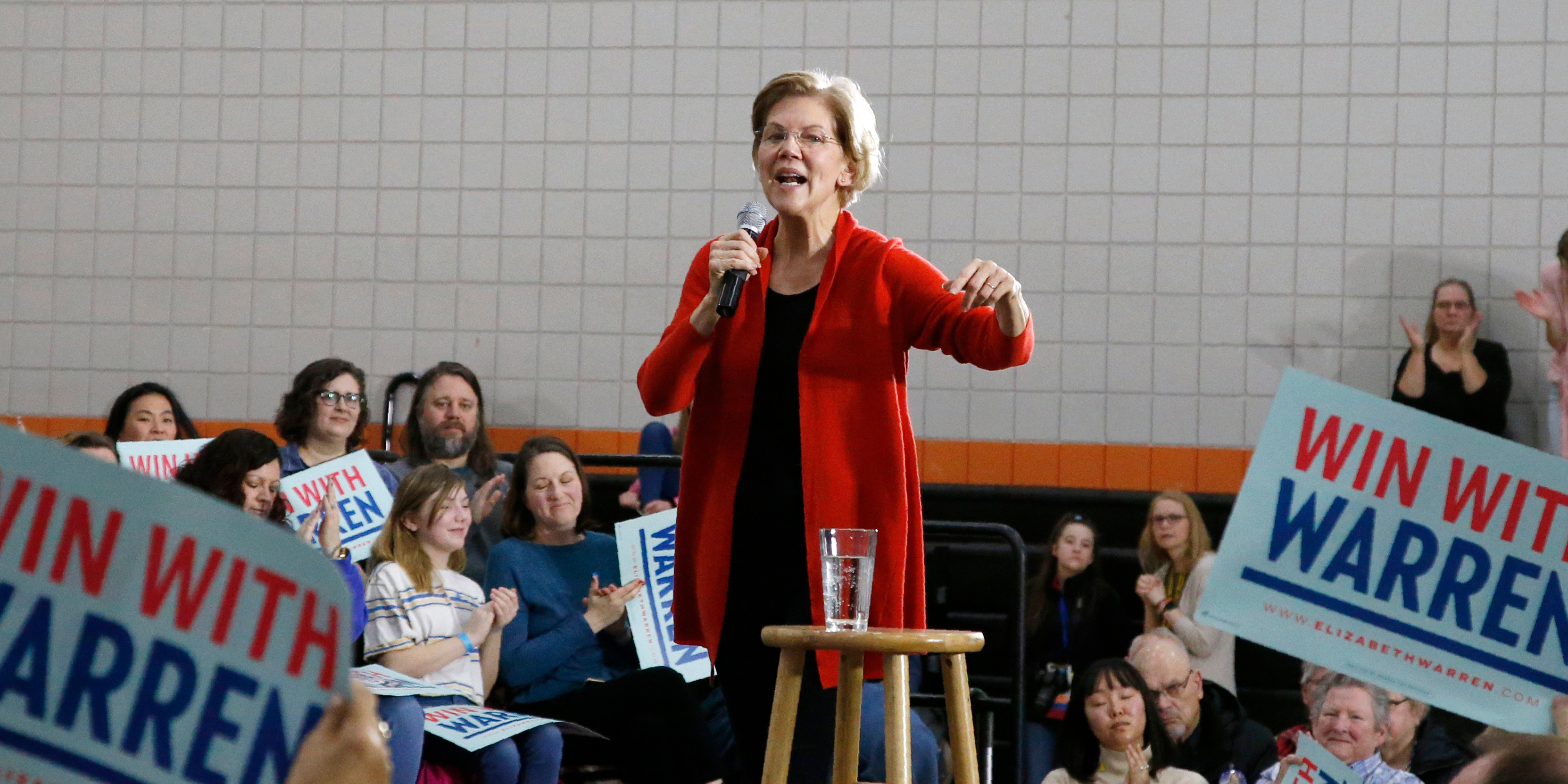

While Sen. Bernie Sanders holds a narrow lead over the rest of the field in Iowa, most recent polls of the state show the leading four candidates – Joe Biden, Sanders, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, and former Mayor Pete Buttigieg -bunched closely together in the double-digit range, meaning the caucuses are still largely up for grabs.

The number of candidates polling in double-digits means that on caucus day, it’s very likely that no one candidate will immediately hold a clear lead in delegates – and the proceedings could go late into the night.

Why are the Iowa caucuses so important?

Since 1972, Iowa has been a huge deal simply by virtue of being first in the Democratic nomination process and setting the tone for the rest of the process.

As the Des Moines Register notes, Iowans pride themselves on being exceedingly well-informed and engaged, and take their role in shaping the race very seriously.

While the state may not be a make-or-break contest, it has historically played an important role in narrowing the size of the field and determining which candidates are viable going forward. An old saying posits that there are only three ways out of Iowa: coming in first, second, or third place.

For some candidates, like President Barack Obama in 2008, either outright winning or being perceived as the Iowa winner transformed them from a longshot contender to a frontrunner.

Obama was certainly a formidable contender going into Iowa, proving that he could build a grassroots operation capable of beating former Senator Hillary Clinton and her significant establishment backing.

In 1976 when Jimmy Carter was running for president, a plurality of caucusgoers was technically "uncommitted." But since he was the highest-placing candidate and vastly outperformed expectations, the media narrative framed him as the winner and he went on to secure the nomination.

How are caucuses different from primaries?

Of the first four nominating contests, Iowa and Nevada hold caucuses run by their respective state Democratic parties, while New Hampshire and South Carolina hold primaries run by the state government agencies.

In traditional primaries, voters go into a voting booth and cast a ballot expressing their choice for the Democratic nominee. Delegates are then allocated proportionally based on the results of that vote.

Caucuses, however, are much more communal and collaborative. Every caucus-goer is assigned to a caucus location, like a high school gym, for example, in their voting precinct where they gather in groups, deliberate, and use preference cards to publicly express their choice for the Democratic nominee instead of casting a secret ballot.

The caucus model has been criticized, however, for being inaccessible to people with disabilities, elderly Iowans, people who don't work a typical nine-to-five schedule, and parents of young children. As Iowa-based writer Lyz Lenz recently reported, women, in particular, are more likely to be the primary caregiver in their household and are often excluded from caucusing altogether.

In an effort to make caucuses more inclusive for those who can't feasibly be in the same place caucusing for hours on end, the DNC has helped both Iowa and Nevada adopt reforms to make it easier to participate.

Iowa will hold multiple satellite caucuses to accommodate people who cannot physically attend caucuses or who are living abroad, and Nevada will hold four days of early voting, in addition to establishing caucus sites at the Las Vegas strip for casino workers who work night shifts.

How do the Iowa caucuses work?

There are some unique features of the Iowa caucus that are important to understand to make sense of the process.

Unlike a regular winner-take-all election in which the person who breaks 50% of the vote wins the whole thing, candidates earn delegates proportionally based on their vote share.

And while 27 out of 41 of Iowa's pledged delegates are allocated proportionally at the congressional district level, there is a minimum threshold in Iowa and most other states contenders must attain to earn delegates.

In Iowa and most other early primary states, a candidate must break 15% of the vote in a given congressional district to win any delegates from that district at all.

Candidates must also clear 15% of the vote at the state level to earn any of Iowa's five Party Leader and Elected Official, or PLEO, delegates and its nine at-large delegates, all of which are allocated based on the state popular vote. This means its possible for candidates to win district-level but not PLEO or at-large delegates. (Iowa also gets eight automatic delegates or "superdelegates" who are not immediately allocated to a candidate).

But there's a catch: Every Iowa precinct with a caucus holds not one but two rounds of preference expression, or alignments, meaning that caucusgoers' second choices are more important, and there will be lots of strategizing behind who they choose to back.

If a caucusgoer's first-choice candidate doesn't break the delegate threshold on the first alignment, they can either switch their preference to a candidate who is viable after the first round in their precinct, try to combine forces with other caucusgoers to make their original first-choice candidate viable on the second alignment, or categorize themselves as an uncommitted caucusgoer.

A caucusgoer whose first-choice is viable after the first alignment cannot, however, is locked into their preference and cannot change their vote, meaning candidates can only gain and not lose votes in the second alignment.

On caucus night, the Iowa Democratic Party will report three separate sets of results that may show different winners:

- The raw vote counts from the first alignment, or preference expression.

- The vote count from the second alignment, which determines what candidates pass the viability threshold to receive delegates in each precinct and congressional district.

- Each candidate's vote share from the second alignment are converted into what are called "state delegate equivalents," or the estimated number of delegates each candidate is allocated from the congressional district and statewide results of the caucuses.

Because the Democratic nomination is ultimately decided by who wins the most delegates and not the most votes, major election forecasters including the Associated Press and Decision Desk HQ (who Insider is partnering with for caucus night) will call the results based on the leader in state delegate equivalents.

This means that the candidate who receives the most votes may not necessarily win the most delegates, making the actual "winner" up to some level of inference.

As Jonathan Bernstein recently noted in Bloomberg opinion: "'Winning' in Iowa, and in the New Hampshire primary a week afterward, has always been a combination of raw results, candidate spin and media interpretation."

Foto: Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) arrives on stage at a campaign event for Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) at the Ames City Auditorium on January 25, 2020 in Ames, IowasourceWin McNamee/Getty Images

Foto: Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) arrives on stage at a campaign event for Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) at the Ames City Auditorium on January 25, 2020 in Ames, IowasourceWin McNamee/Getty Images

Why might Iowa be less relevant this year than in previous cycles?

With an unusually large Democratic presidential field, Iowa may be less important this year than ever.

A recent Politico Magazine analysis found that 2020 Democrats are spending much less time in the state ahead of the caucus than Democratic candidates in previous cycles, choosing instead to shore up support in states with far more delegates and high-dollar donors.

In another notable twist, Democratic candidates in this cycle have criticized the DNC outright for putting Iowa and New Hampshire -- states that are overwhelmingly white -- first in the Democratic nomination process, which they argue puts candidates of color at a disadvantage.

Given the fact that seven candidates are jostling for a win in Iowa and have qualified for the February 7 debate in New Hampshire ahead of the state's February 11 primary, they may not necessarily take a loss in Iowa as a sign they should suspend their campaigns altogether.

While Iowa gets a disproportionate amount of attention from both candidates and the media by virtue of going first in the country, it also only holds just 1% of the total pledged delegates allocated throughout the nomination process from every US state and territory.

Because Iowa just accounts for 1% of delegates, it's entirely possible for a candidate to not come in first or win many delegates in Iowa at all, and go on to win the nomination, just as Trump did in 2016 after Sen. Ted Cruz won Iowa.

This is especially true for candidates like Biden and Sanders, who already hold significant support in delegate-rich parts of the country that vote later in the primary process, like the South and Midwest.

The results of the Iowa caucuses will likely be more important for candidates like Warren, Buttigieg, and Sen. Amy Klobuchar who are going all-in on Iowa and are relying on a strong performance in the state to fuel their campaigns forward.

If Buttigieg or Klobuchar earn very few or no delegates in Iowa - the state in which they've invested the most resources - it'll be a bad sign for their campaigns and could hinder their abilities to compete in future contests.

Read more:

Iowa's biggest newspaper endorsed Elizabeth Warren ahead of the state's February 3 caucuses

Here's how Democrats will elect their presidential nominee over the next several months