How do you convince someone to pay $1,000 for a drug when they can buy an identical alternative for $100?

Valeant Pharmaceuticals has one answer: Pay fat rebates to the people who decide whether your insurer covers the drug.

The drug in question here is Solodyn, an acne-treating antibiotic. Its sales had tumbled by 40% since it went off patent in 2011. Then Valeant struck a deal with a specialty pharmacy called Philidor and started to turn things around.

In early 2015, after Philidor was on board, Solodyn sales jumped 56%, according to internal documents obtained by Business Insider.

Philidor is by now a well-known name to Valeant’s investors. Although Valeant had close ties to the company and was counting on it to grow the volume of sales of some of its key drugs, its existence was known only to Valeant until last October. When it was exposed, Philidor’s tactics and Valeant’s growth-at-all-costs business model came under fire, federal agencies began to investigate, and Valeant’s once high-flying shares collapsed.

Rebates aren't uncommon in the drug industry, and Valeant's new leadership is more open than its predecessors about the role they play in driving sales, but as the company tries to put itself back together again, the question of how much profit it's sacrificing to maintain market share and move a high volume of drugs is in the spotlight.

The company on Tuesday reported earnings that were well short of expectations, prompting one analyst to say "It appears Valeant's core business continues to deteriorate."

Sales of Solodyn reported by Valeant have tumbled to $26 million in the third quarter from $66 million a year ago, when Philidor was still in the picture. This is despite data from IMS Health and Bloomberg indicating a rise in total prescriptions.

How is this possible?

The documents obtained by Business Insider show that, with Philidor at least, Valeant was giving away millions of dollars worth of Solodyn to drive sales volume.

The documents, which refer to its business in the first quarter of 2015, describe an approach called the "Philidor strategy." Its aim was to move a high volume of drugs by paying high rebates to the insurers and pharmacy benefit managers that decide whether to cover a drug that has been prescribed to a patient.

Pharmacy benefit managers are middlemen that take a large cut of sales, and they're used across the pharmaceutical industry. Ostensibly meant to keep drug costs down and help businesses and insurers wade through the many alternatives available to a patient, the PBMs wield a lot of power in terms of ensuring a drug company's access to covered customers.

Paying huge rebates to PBMs and insurance companies was a way to ensure Solodyn would be covered even when cheaper generic alternatives were available.

According to the documents, rebates to payers for Solodyn were as high as 80.7% when the drug was sold through Philidor, but they also varied widely - typically depending on a payer's size and market share.

By late 2015, those rebates combined with Philidor's aggressive sales tactics turned Solodyn into Valeant's seventh-best-selling drug. Once Philidor was out of the picture - Valeant quickly broke off the relationship after the scandal over the pharmacy erupted - Solodyn dropped to 22nd among Valeant's top 30 products.

Elif McDonald, Valeant's director of investor relations, would not comment on the documents when reached Monday, pointing Business Insider to the company's external spokespeople at Sard Verbinnen. They have not responded to requests for comment on the documents.

How to be useful

Valeant's goal at Philidor was to sell as much product as possible, even at a loss. Losses often occurred when the pharmacy sent medications when their payments hadn't been approved yet. That was marked as gross revenue. If the insurer ultimately rejected Philidor's claim, Valeant would just eat that cost, bringing down the company's net revenue.

In the presentation, the company refers to these losses as "alternative fill" subsidies. They were the problem Valeant was trying to solve in the presentation Business Insider looked at, titled "Solodyn and Jublia Economic Analysis and Factbase." It's dated August 9, 2015 - two months before Valeant started to crash.

"Lower margins were primarily due to AF (Alternative Fill) subsides - 'free goods' that are fully reimbursed by VRX - which accounted for 32% of Solodyn and 14% of Jublia gross sales in Q1 2015," the presentation says.

Profit margins aside, Philidor was a huge success in terms of driving volume, and that is most apparent in its effect on Solodyn sales. Before it started selling Solodyn, sales of the drug were on a steady decline.

In 2011, the drug had $789 million in sales, according to Symphony Health Solutions. By 2014, right before the Philidor acquisition, that number dropped to $480 million because of pricing pressure from generic competition.

In 2015, Valeant sold $506 million worth of Solodyn, and the company had Philidor to thank for that.

In Q1 2015, "gross sales" of Solodyn shot up 56% from the same time a year before, the documents say. The bulk of those sales came from Philidor. But remove all the payments that Valeant had to make to generate those sales, and the figure falls from $172.5 million to $41.7 million, the documents show.

That's before factoring in other costs such as the manufacturing of the drug or expenses related to running the business.

Fattening the margins

Valeant was trying to figure out how to get insurers to pay for more prescriptions to fatten Philidor's margins. The payers are referred to as MHCs in the presentation.

"There is room within the current MHC contracting to increase profitability/'pull through' the full value of current contracts," it said.

Pull-throughs are incentives to get more people to use a certain drug versus a cheaper version - say, a generic.

The company realized it made the most money from drugs that were covered by insurers that didn't have strong prior authorization restrictions. PAs require doctors to get a payer's permission before prescribing a drug.

So the idea was to make sure Solodyn and Jublia, a toenail fungus treatment, had the easiest status with as many payers as possible. To entice payers, Valeant simply hiked up the rebates "to incent payers to adopt less stringent PAs," the presentation said.

It also recommended investing "in failed PAs to obtain covered [total prescriptions] in return, based on share of these failed PAs that get approved."

Valeant also wanted to make better use of plans that implemented step therapy for Solodyn. Step therapy is when your healthcare plan requires you to try a cheaper form of a drug you were prescribed to see if that works before you buy the more expensive prescription.

The average market share for Solodyn on plans that required step therapy or prior authorization was 6%. In contrast, Valeant had 14% of the market share in plans in which Solodyn was on the formulary - the list of drugs a payer has agreed to cover - and 17% of the market share among plans in which Solodyn was preferred.

Valeant's strategy on the step therapy side was to work on removing it from plans with low market share, and to try to reduce rebates and change its status with "outliers" - payers that got high rebates from the company but in which Solodyn had a lower market share.

Said plainly, Valeant was trying to figure out how much it had to pay in rebates to get MHCs to overlook how uneconomical and impractical Solodyn might be.

What your pharmacy benefit manager won't tell you

The terms of PBM contracts are variable and secret. The more lives a PBM covers, the more leverage it tends to have in negotiating steeper rebates, which is why some PBMs may walk away with rebates twice as big as those of their competitors.

The lack of transparency has its pros and cons. On the one hand, having these contracts under wraps keeps a drug manufacturer from knowing what its competitor is getting as a rebate. If it knew, the company could argue it shouldn't have to pay a bigger rebate than the other.

In 2004, the Federal Trade Commission argued against PBM contract transparency, saying that would make it harder for there to be competition that would drive down prices.

On the other hand, without a clear picture of the rebates, the public's understanding of why the prices of prescription drugs continue to climb is limited to just the price we see at the pharmacy counter, or data based on the list price (which no one actually pays). Without it, we don't know how big a cut each part of the supply chain gets.

The Valeant documents Business Insider saw break down the rebates on Solodyn in Q2 2015:

- Caremark Performance took a 70% rebate for Solodyn and a 36% rebate on Jublia. Express Scripts National Preferred took a 39.4% rebate for Solodyn and a 29.4% rebate for Jublia. UnitedHealthcare Advantage took an 80.7% rebate for Solodyn and no rebate for Jublia. Anthem Blue Cross in California took a 39.4% rebate for Solodyn and a 29.4% rebate for Jublia. OptumRx 3 Tier Traditional took a 62.5% rebate for Solodyn and no rebate for Jublia. Humana Rx4 Traditional took a 66.4% rebate for Solodyn and no rebate for Jublia. Aetna Premier Commercial took a 45% rebate for Solodyn and no rebate for Jublia. Tricare Uniform Formulary 39.4% rebate for Solodyn and 29.4% rebate for Jublia. Federal Employee Program Standard 70% rebate for Solodyn and 36% for Jublia

It's clear that Valeant felt as though it had to work a little bit harder to entice payers to pay for Solodyn than for Jublia, and it's not hard to understand why.

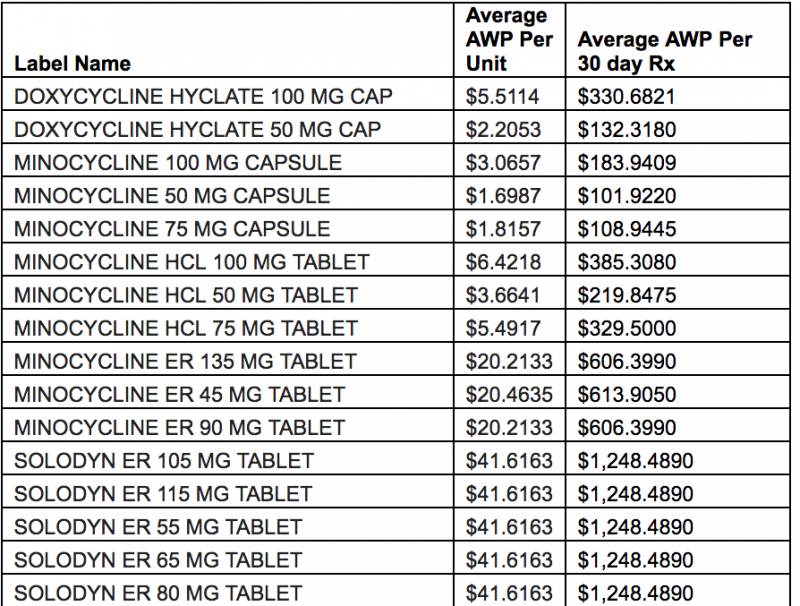

Tons of cheaper Solodyn competitors are on the market. When Business Insider asked Andrew Miller, the vice president of operations at Detroit-based PBM MeridianRx, why he doesn't have Solodyn on his formulary, he sent the data below.

"Solodyn is a once-daily, extended release form of minocycline. The therapeutic alternative would be the generic minocycline immediate-release twice-daily. Solodyn contains the same therapeutic ingredient in a different dosage form, offering no superior therapy. Below is the average [average wholesale price] pricing."

Never duplicated

After Philidor closed, Valeant acted quickly to try to create another channel for many of its products, including Jublia and Solodyn, through a deal with Walgreens. In an interview with CNBC in December, former CEO Michael Pearson said the agreement, which would include a co-pay program and steep discounts for branded drugs, was primarily meant to drive sales volume.

Pearson also said that the Walgreens deal would remove some middlemen in the business. It's not clear what he meant by that. The documents Business Insider reviewed show that Philidor spent very little on wholesalers or any other middlemen compared with what it paid in rebates to the gatekeepers between their drugs and the plans that paid for them.

What is clear is that paying off the gatekeepers is still important to the success of the Walgreens deal. Valeant said so in its 2015 annual report, and it reiterated that sentiment in its third-quarter call on Tuesday, saying it would give MHCs higher rebates. Chief Financial Officer Paul Herendeen cited higher rebates as a reason net prices were down in the company's gastrointestinal, dermatology, and diversified products businesses.

This isn't illegal, but it means there are incentives in the system that help companies maintain a $1,000 price tag on a drug with cheaper alternatives. We don't usually get such a close look at how those work.

If you know more about PBM contracts with drug companies like Valeant, please contact us at [email protected] or [email protected].