- Dugway Proving Ground tests and stores some of the deadliest chemical and biological agents on earth.

- The facility, which opened in 1942, covers about 800,000 acres – larger than the state of Rhode Island.

- Past experiments include weaponized mosquitoes and fleas, as well as tests with deadly diseases such as anthrax.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Following is a transcript of the video.

Narrator: In 1968, about 6,000 sheep died near this government facility. They were poisoned by a chemical weapon named VX.

The US hasn’t been known to actively use VX in combat. In fact, it’s begun destroying its stockpile of chemical munitions as part of a UN treaty. But it’s just one of many strange and secretive experiments that happened within these walls. Experiments on sheep, mosquitoes, and even civilians.

About 85 miles southwest of Salt Lake City is the US government’s top-secret bioweapons lab. It’s called the Dugway Proving Ground. The 77-year-old facility covers about 800,000 acres. That’s just a little larger than the entire state of Rhode Island. And it tests some of the deadliest chemical, biological, radiological, and explosive hazards on Earth.

Less famous than Area 51, Dugway dates all the way back to 1942. Right in the middle of World War II.

Clip: The decisive battle of war has begun.

Narrator: The government needed a large area to test powerful weapons, eventually settling on this stretch of land in the Utah desert. Back then, the site was used to test everything from chemical sprays and flamethrowers to various antidotes and protective equipment, and even fire-bombing.

After World War II, Dugway mostly shut down. Until the Korean War began in 1950. That's when the proving ground turned into what it is today: a permanent military base. In Dugway's first few decades, the base worked mostly on offensive weaponry: biological and chemical munitions designed to directly attack enemies.

Clip: Sampling devices, positioned throughout the test area, yield valuable information to chemical core researchers.

Narrator: The 1950s, for example, saw the launch of Operation Big Itch, an experiment that was testing weaponized fleas. The fleas weren't infected with any type of disease or agent, but experimenters were working with thousands of them. And the fleas were dropped in cluster bombs, to gauge if they would survive the fall from an airplane. And this was only part one. Dugway launched a second experiment, called Project Bellwether, in the 1960s. Only this time, mosquitoes were injected with inert diseases, inert bacteria, and inert viruses. But get this: Those mosquitoes were released upon several groups of human volunteers, who were bitten again and again during the trials.

And there are records dating back to the late 1950s, which describe experiments that used infected mosquitoes. And those are just two experiments known to the public. Exactly what goes on at Dugway is, well, pretty unclear. And that's not by accident.

The area is intensely guarded. Everything that comes in and out is carefully monitored, guards are on constant patrol and actively armed, and the perimeter is lined with tall, barbed-wire fencing. There are even signs that authorize "deadly force" when necessary.

Since the 1940s, officials say operations have shifted from offensive to defensive tactics. Case in point, most of the current known work prepares agents to defend against potential biological and chemical attacks. For example, a multitude of training programs are held on-site for the armed forces.

Here's one in which Army Reserve soldiers are tasked with checking the radiation levels of artillery rounds. And here's another where soldiers were tasked with identifying substances in a simulated chemical lab.

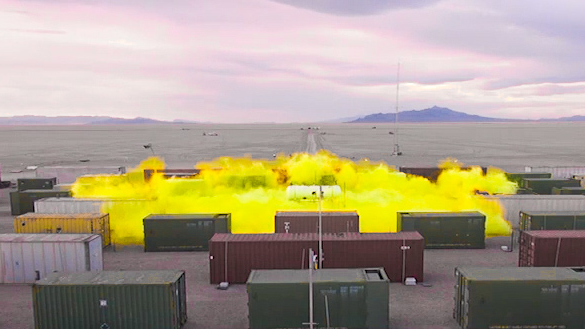

Dugway's main operations include the "BRAUCH" training facility, constructed from various shipping containers. It simulates underground environments for military training. There are also various buildings and rooms that serve specific purposes. Like the decontamination testing chamber, the wind-tunnel testing room, and the material test facility.

But perhaps the most interesting room of all is this: the Smartman Laboratory facility, which houses the Smartman dummy, a model that's used to simulate human contact with chemical agents, including the infamous VX nerve agent. Specifically, the Smartman helps the lab develop more effective individual protection respiratory equipment,- essentially, gas masks and the like.

A variety of chemists, chemical analysts, and technicians work on-site. And the use of airtight chambers and gas masks is not only common, but mandatory. Despite all of this dangerous experimentation, the work done at Dugway hasn't always been properly contained.

Remember that sheep incident? That marked the start of a worrisome track record. It happened when overhead planes spewed out the nerve agent into the wind, accidentally sending it into nearby farmland in Skull Valley. Within the next couple of days, farmers found thousands of sheep dead in their fields. The Army compensated the farmers and lent them bulldozers to bury the sheep. But the accident sparked a whole debate on the use of chemical weapons in warfare.

Adding on to these questionable practices, a 1994 Senate hearing on veterans' health focused specifically on Dugway veterans and civilians. A report found that people at Dugway were exposed to biological and chemical simulants believed to be safe at the time, but that the Army had later stopped using many of them because "they realized they were not as safe as previously believed."

One veteran, who was accidentally sprayed in the face with the chemical DMMP in 1984, found himself wheezing and coughing the next day - symptoms that ended up lasting several weeks. Despite this, he was given only cough medicine and antibiotics by the Dugway Army Hospital. The Dugway Safety Office assured him that the chemical was safe. But by 1988, officials at Dugway had reevaluated the simulant's danger and were concerned it could cause cancer and kidney damage.

In 2011, the facility slipped up again: It went on lockdown after workers lost a vial containing the VX nerve agent. Nobody was permitted to enter or exit the facility, not even the employees.

And in 2016, the CDC and the Department of Defense launched a major investigation when a review team found that Dugway had been operating dangerously for several years without the government's knowledge. USA Today reported "egregious failures" by the facility's leadership and staff. The reports singled out the head colonel in command at Dugway, Brig. Gen. William King.

The Army's accountability investigation recognized King as unqualified, lacking the education and training to effectively oversee biosafety procedures crucial to Dugway's operation. The report admonished him, saying he "repeatedly deflected blame" and "minimized the severity of incidents." It even says King "fails to recognize" how serious the incidents truly were. And how serious were the incidents, exactly? Well, under King's command, the facility mistakenly shipped live anthrax to other labs. And not just once, but multiple times. For over a decade.

That same report revealed that workers had been regularly and deliberately manipulating data in important records. Records meant to verify that pathogens being transported elsewhere were killed and safe for researchers to handle without protective gear. Still, the facility's shady past, secretive operations, and intense surveillance have captured the attention, and skepticism, of some closer observers, including several conspiracy-theorist groups.

There are suggestions that the facility is the "new Area 51." And the local community has raised their own questions about the facility's operations. Dugway was even featured in an episode of The History Channel's "UFO Hunters," in which local residents and UFO watchers were interviewed and footage from the area was examined. It's hard not to wonder, when you live in close proximity to such a restricted landscape.

Despite these theories, Dugway has expressed a desire to be "more transparent." And representatives have said the facility wants to be "more a part of the local community" by better informing citizens about what exactly goes on there. So far, they've delivered some on that. The facility has its own events page, which lists several events open to the general public and the local Utah community. This year, they're hosting a trail race on the facility grounds.

Certainly, today's Dugway is a far cry from the 1940s Dugway, which was entirely closed off to the public. But despite the shift in the level of secrecy, much of Dugway's testing remains classified, preserving the skepticism and mysteriousness surrounding the facility.