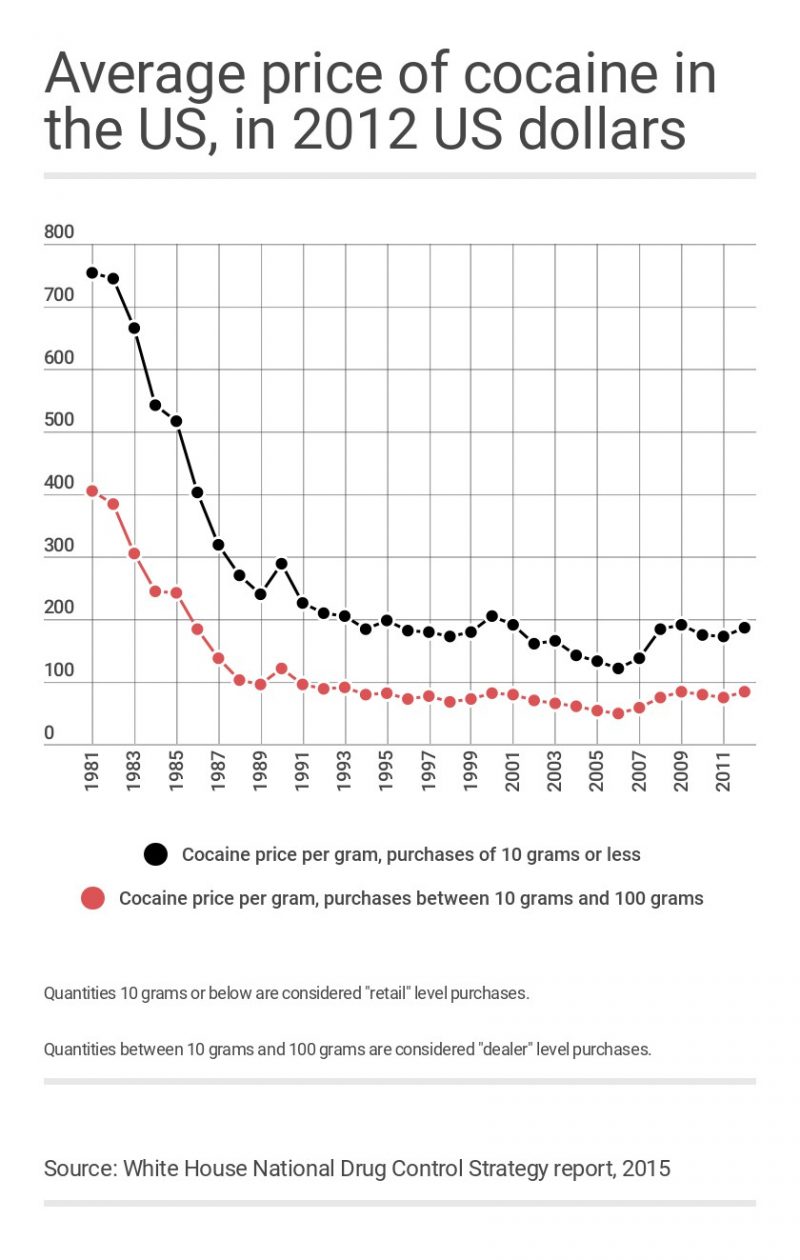

Cocaine has been a high-profile feature of the American drug world since it arrived in the US in the early 1980s.

But since those first few years on the scene, cocaine prices have remained relatively stable, with variations in year-to-year prices in the US likely being driven by foreign affairs as much as by domestic demand.

Precise figures for the movement and sales of illegal drugs are obviously hard to come by.

The cocaine trade, like the drug trade in general, is opaque and run by individuals and groups that are hostile to oversight and inquiry.

Accordingly, analysis of drug prices and how they've change over time involves quite a bit of speculation, but the charts below, documenting the shifts in cocaine prices in the US, grant some insight to how the market has evolved over the last 30 years.

While cocaine prices in the US have varied some year to year, they have held relatively stable since declining from highs in the 1980s.

"What happened is there was fluctuation in terms of cocaine ... in the '80s it was predominantly Peru that was the biggest producer of coca," cocaine's base ingredient, said Mike Vigil, a former chief of international operations for the US Drug Enforcement Administration.

Peru has remained a large producer of cocaine, but Colombia has recently taken the mantle as the largest producer.

"And those fluctuations there, between Peru and Colombia, the negotiations" between Colombia and the FARC rebel group that aimed to bring the rebels out of the drug trade, "all of that causes fluctuations in the market," Vigil, author of "Metal Coffins: The Blood Alliance Cartel," told Business Insider.

"But ... cocaine in the United States has not seen a spike. It's remained relatively stable during the course of the last several years."

Cocaine prices in the US underwent a precipitous decline between the early 1980s and the early 1990s.

The drop in US cocaine prices in the 1980s coincided with the entry of Pablo Escobar and other Colombian traffickers to the trade, bringing newfound organization and brutal efficiency.

"The plummeting of the price of cocaine in the US in the 1980s reflects the industrialisation of the cocaine business by Pablo Escobar and others," Tom Wainwright, the Britain editor for The Economist and author of "Narconomics," told Business Insider, adding:

"Previously cocaine had trickled into the US in relatively small consignments. Smugglers like Escobar transformed it into a professional business, exporting cocaine by the plane-load."

"Economies of scale reduced their costs. And the sheer amount of product flowing into the United States meant that prices fell, as supply outpaced demand (which itself grew pretty rapidly between the 1970s and 80s)."

Escobar and the Medellin cartel - particularly Carlos Lehder and George Jung, smugglers who met in a Connecticut prison cell - helped accelerate the flow of cocaine to the US, shunting it north by plane.

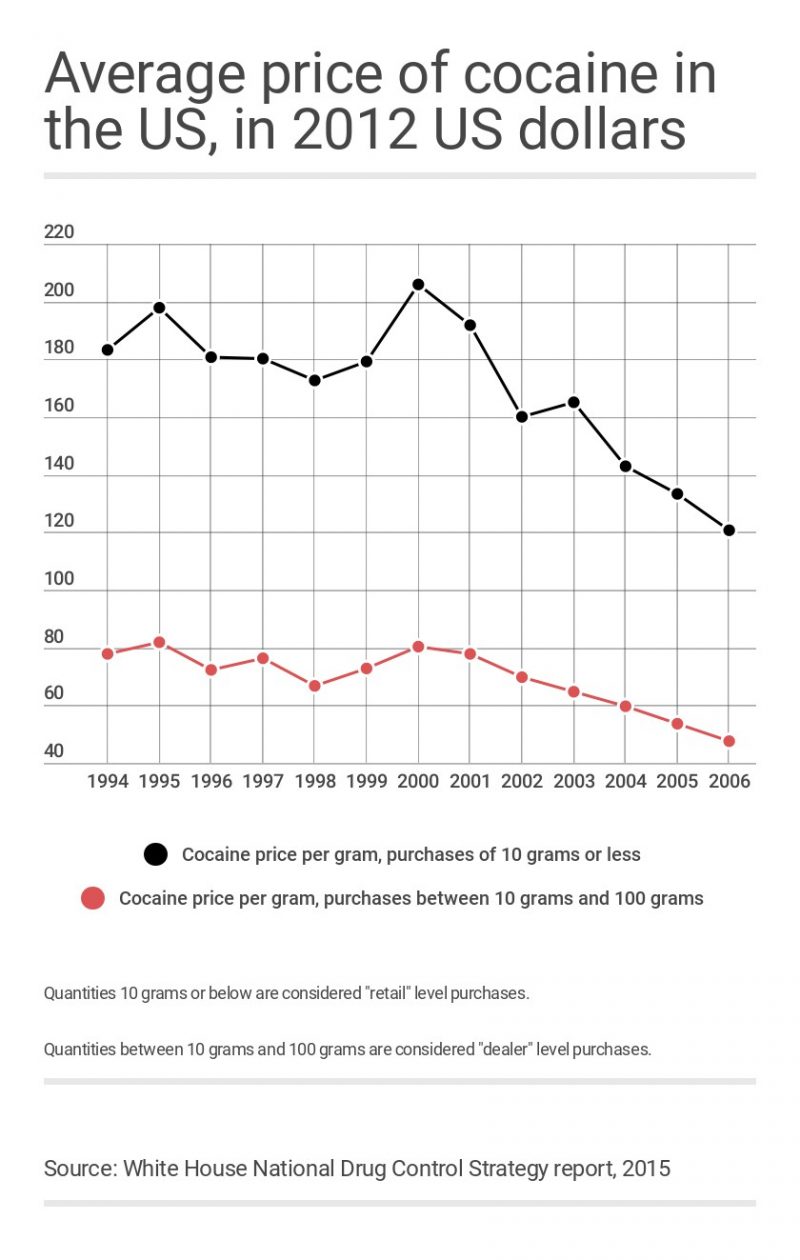

Prices in the US continued to decline in the late 2000s and early 2000s, likely the result of a confluence of factors.

"It looks more like a continuation of a downward trend that had been established much earlier. This downward trend was partly caused by an increased professionalisation of the cocaine business," Wainwright said. "Manufacturers in South America improved the process they used to extract cocaine from coca leaves, allowing them to increase production without having to grow any more crops."

Turmoil in the narco underworld may have also contributed to the decline in prices.

After Escobar's high-profile killing in 1993 and the subsequent break up of the rival Cali cartel, control of the cocaine trade in Colombia fell to smaller organized-crime groups, paramilitary groups, and rebels like the FARC.

Many of those groups were connected to each other and to Colombian elites, but the expansion of actors involved in the cocaine trade could have put downward pressure on retail prices.

Uncertainty may have also been injected into the drug market by instability in Mexico, where some cartels, led by Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán's Sinaloa cartel, fought for control of lucrative smuggling routes during the 1990s and 2000s.

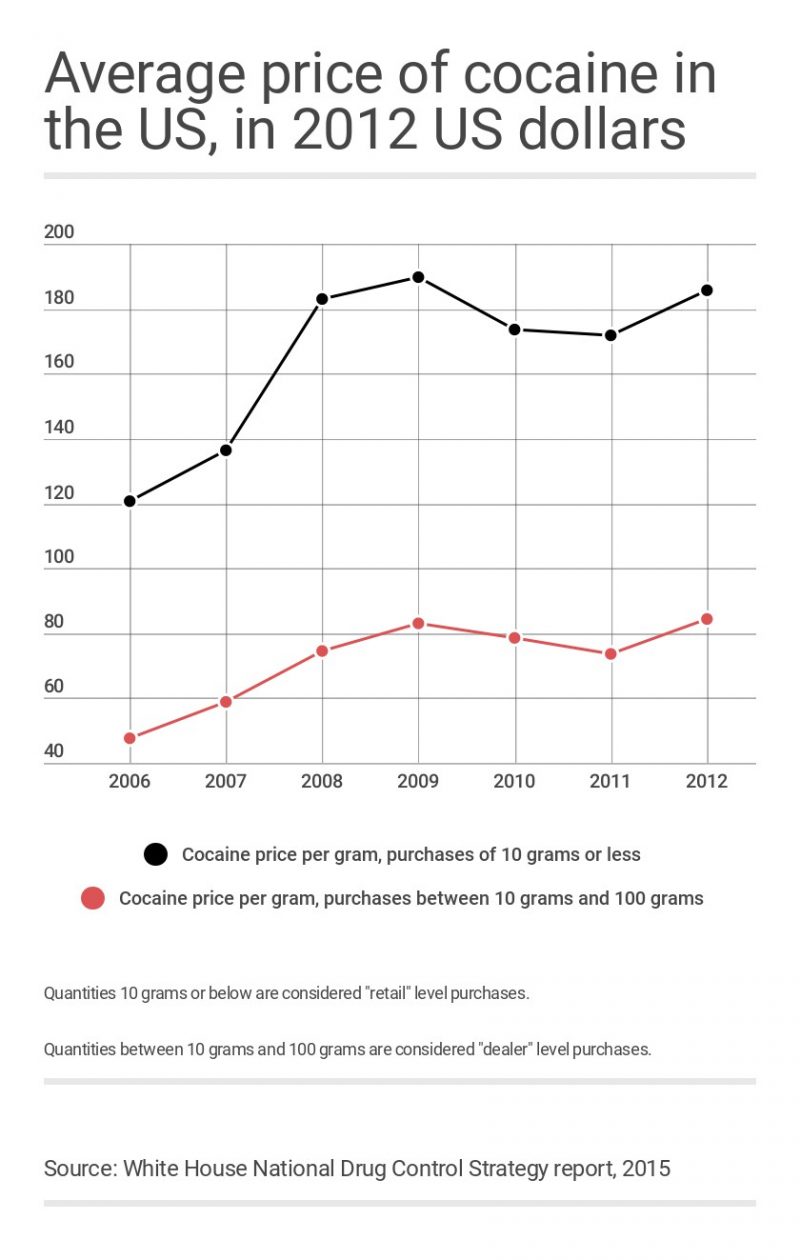

In the late 2000s and early 2010s, US cocaine prices began to creep up from lows seen in the mid-2000s, probably for a combination of reasons.

"This was exactly the point at which Calderón's war against the cartels got going, and the level of violence in Mexico shot up," Wainwright told Business Insider, referring to then-President Felipe Calderón's crackdown on the drug trade. "This fighting certainly would have increased cartels' costs. And it may have interrupted the supply of cocaine to the US, causing prices to rise."

Drug-related violence in Mexico jumped during the 2009-2010 period, especially in the Ciudad Juarez area, just across the border from El Paso, Texas. Ciudad Juarez was and is a highly lucrative drug-trafficking corridor, making it still worth fighting over today.

Law enforcement has also increased its interdiction efforts during this period. In 2014, US officials said the previous three to five years had seen a marked shift by drug traffickers toward Caribbean routes. That shift may not have significantly diminished the amount of drugs flowing north, but interrupting trafficking patterns is one of many things that can cause a rise in prices.

"One other factor to consider: during the early 2000s, demand for cocaine in Europe increased pretty steeply," Wainwright added. "Cocaine is a worldwide business, so extra demand in Europe would, other things being equal, raise prices in the US."

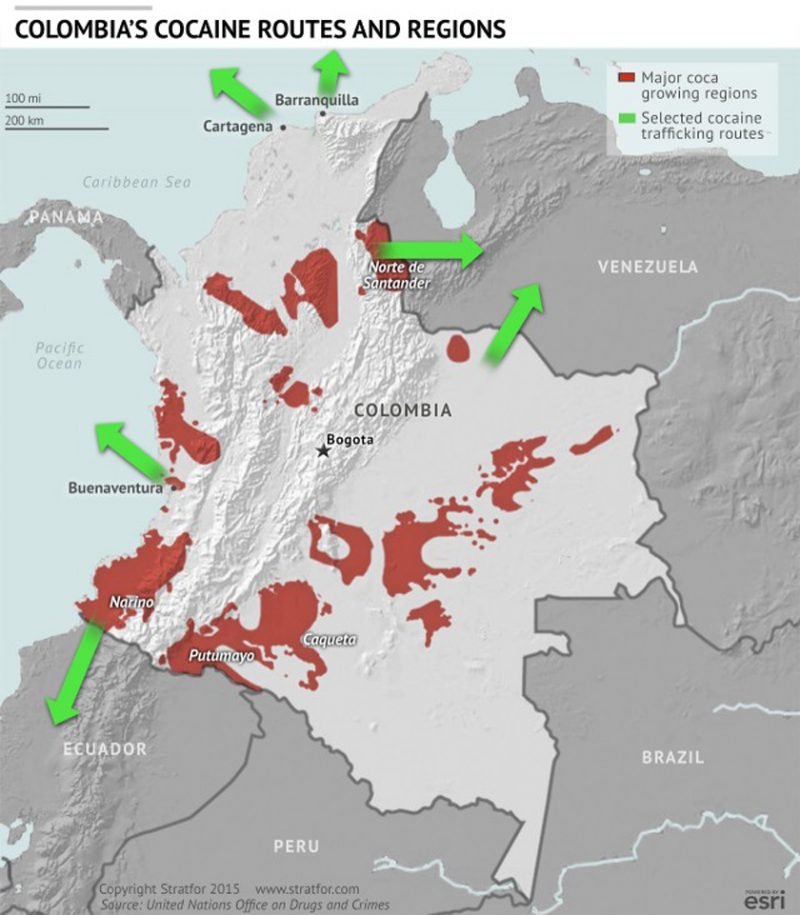

In recent years, Colombia has again taken the title of top producer of coca leaf. Its production of the plant has grown considerably over the last few years, but it's not yet clear what effect this has had on US prices.

A July report from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime showed coca production in Colombia increased 40% between 2014 and 2015, growing from about 170,500 acres to about 237,200. In 2015, the total acreage under cultivation was double the amount found in 2013. (The US government estimated a 42% increase in 2015, to 393,000 acres.)

"Once again, it's taken over as number-one producer, and that happened here within a year or two because the FARC, while they were in heavy negotiations in Havana with the Colombian government, they started to force the farmers to grow more coca," Vigil said.

The FARC is suspected of pumping up coca production in order to take advantage of aid that would have been offered as a part of eradication programs had the rebel group signed a peace deal with the Colombian government. (Colombian farmers who are not members of the FARC also have a vested interest in taking advantage of the lucrative coca trade.)

The FARC-Colombia peace accord is in limbo after Colombians narrowly rejected it in a plebiscite held in early October. But had that peace deal been signed, or if it is signed in the future, it's unlikely that the FARC presence would disappear from the cocaine trade.

"I would say that [the deal] will eventually go through, but ... when the FARC and the Colombian government sign that peace accord, a lot of members of the FARC will ... just go into the drug trade completely," Vigil told Business Insider, adding:

"And that's going to have a significant impact, and then, coupled with the Maduro government allowing the FARC and a lot of major Colombian drug cartels to operate freely on Venezuelan soil, it's going to create a very volatile situation for the United States and a lot of European consumer countries."

"They've tasted the money, they've tasted the power, the wealth that comes from drug trafficking, and a lot of these guys are going to go full bore into the cocaine trade."

Whoever's producing it, and where ever it's being produced, there's little doubt that cocaine will still flow around the world, and that much of it will end up in the US.

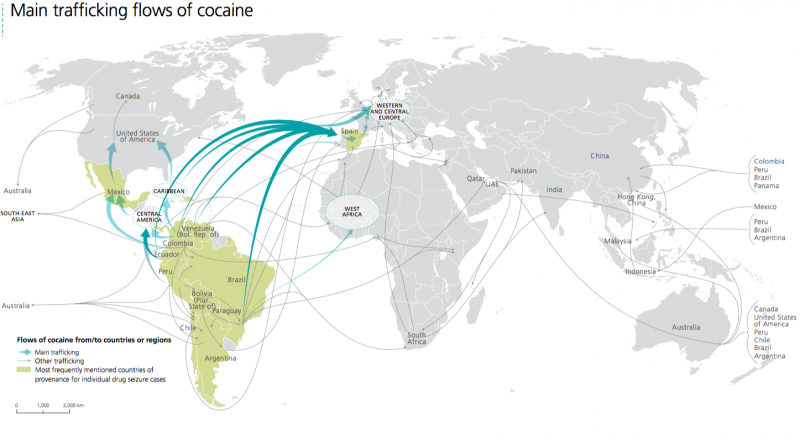

"In general, US cocaine comes from Colombia and European cocaine comes from Peru and Bolivia. But it's not hard to [change] routes and suppliers," Wainwright told Business Insider.

"In the same way, if Colombia gets better at suppressing cocaine production, Americans may end up consuming more Peruvian and Bolivian cocaine. It's the same stuff. To the source countries, of course, it makes a big difference," he added.

"If peace does break out in Colombia and if that does reduce cocaine production, I would want to keep a close eye on Peru and Bolivia." Wainwright went on. "The trade isn't going away."