- The Uber-Waymo trial started on Monday morning.

- The case will determine whether Uber is guilty of stealing intellectual property from Waymo, a self-driving car company that spun out of Google.

- Waymo’s lawyers painted Uber as a ruthless competitor, prepared to win at any cost.

- Uber countered by arguing Waymo is motivated by fear of losing talent, and disputes that the “trade secrets” are in fact trade secrets.

- Waymo is seeking damages from Uber, as well as a permanent injunction blocking it from using the tech.

SAN FRANCISCO – Uber and Waymo are finally squaring off in court.

On Monday morning, the long-anticipated trial between two of Silicon Valley’s most powerful tech companies got underway – one year after Waymo, the self-driving car business owned by Google’s parent company, accused Uber of stealing key trade secrets behind its technology.

On the first day, the two sides initially worked in broad strokes to paint favourable – and contradictory – narratives.

Waymo depicted Uber as a ruthless competitor, prepared to “cheat” to win at any cost.

Uber's attorney, meanwhile, tried to focus the case more narrowly on the alleged trade secrets themselves, and to distance the firm from the star engineer at the heart of the case - Anthony Levandowski, who worked at Google's self-driving car spinoff, Waymo, before joining Uber following the purchase of his self-driving truck startup in 2016. Waymo alleges that Levandowski took key information with him when he left, and passed it to Uber.

In the opening statement that began the trial, Waymo presented it as "case "about two competitors. One of these competitors decided they needed to win at all costs, losing is not an option, that they'd do anything they need to do to win, no matter what … no matter if it meant doing the wrong thing."

Uber's lawyers fired straight back: "That was quite a story we just heard, a tale of conspiracy between [Anthony] Levandowski on one hand and Uber on the other. I'm gonna tell you right upfront: it didn't happen. There's no conspiracy, there's no cheating, period, end of story."

The trial has been months in the making and underscores the high-stakes battle being waged by Silicon Valley companies as they race to dominate the market for self-driving vehicles. Depending on the outcome, it could have lasting implications for the flow of talent between tech companies - and is acting as a kind of referendum in the public eye on the "most fast and break things" Silicon Valley attitude perhaps best espoused by Uber.

Waymo is seeking damages from Uber, as well as a permanent injunction blocking it from using the technology in dispute.

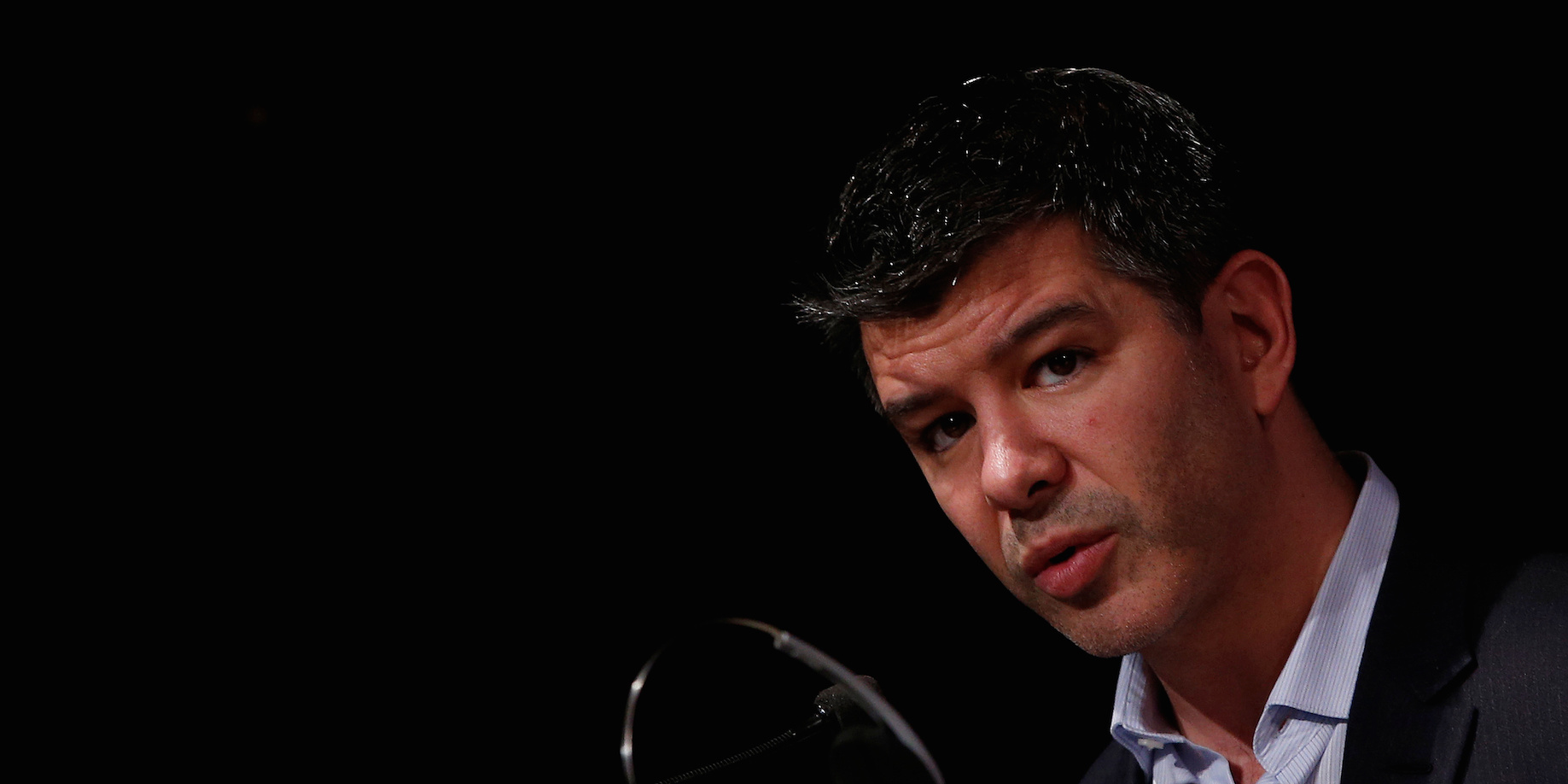

Waymo's lawyers used former Uber CEO Travis Kalanick's bold predictions on the importance of self-driving technology against the company as evidence of how determined his firm was to gain the upper hand, whatever the legal consequences.

In the latter part of their opening statement, Waymo rattled off a litany of documents, quoting private correspondence between Kalanick, Levandowski, and others, purporting to illustrate how they scheme to illicitly obtain Waymo's intellectual property.

"This is all about winning," Kalanick said in one text quoted. "Losing is not an option."

The case hinges in part on exactly how a "trade secret" is defined. Broadly speaking, it is information with economic value that isn't known to the public, or to others who might obtain value from knowing it. But this doesn't extend to professional skills and abilities, making for a fine line between a trade secret and a trick of the trade.

And much of the case will be heard in closed session, so the eight alleged trade secrets in the case can be discussed freely, meaning the press and the public will only get a limited view of proceedings.

Uber argues that the eight alleged trade secrets aren't trade secrets at all. The ride-sharing company's lawyers allege that Waymo brought the case due to concerns over losing talent to Uber and fierce competition in the industry, rather than being motivated by genuine fears over the theft of intellectual property.

After the opening statement, Waymo called its CEO John Krafcik to the stand as its first witness. When cross-examining, Uber's lawyer rattled off a list of high-profile employees the self-driving car unit lost early in his tenure, painting a picture of a company bleeding talent.

Anthony Levandowski was earlier fired from Uber after he refused to cooperate with its legal team, and on Monday the company's lawyers attempted to distance itself from him. "Uber was prepared to take the risk with Anthony Levandowski ... he was the hottest commodity in the whole autonomous vehicle business," they said.

"Just like Google [previously hired Levandowski], the fact Uber brought on board some rockstar engineer doesn't make them guilty of wrongdoing," said Uber's engineers. Later, they said: "At the end of this case you're gonna realize what matters is the tech, not Anthony Levandowski ... You're gonna realize the tech tells the truth."

For Uber, whatever the outcome, the real cost of the case may be the massive reputational damage. The buildup over the past year has produced explosive headlines about the accusations against Uber, and has damaged the company's reputation to the point that William Alsup - the federal judge in San Francisco overseeing the case - has had to clarify that the trial is a dispute over intellectual property and not "whether Uber is an evil corporation."

And while many lurid details have steadily emerged over the past several months, the trial is still likely to be an explosive one. Waymo's first seven witnesses include Waymo CEO John Krafcik, Waymo's VP of engineering Dmitri Dolgov (who briefly took the stand at the end of proceedings on Monday), and former Uber CEO Travis Kalanick.

When Krafcik took the stand, his testimony also provided insight into the alleged differences in approach between Levandowski and Waymo's leadership. Levandowski, he said, was much less atuned to safety issues then he was, arguing Waymo didn't need additional back-up (or "redundant") steering systems in its Chrysler minivan.

Krafcik brought up the "move fast and break things" maxim when describing Levandowski: "Aspects of 'move fast' are really great. 'Break things' is challenging when you're dealing with a car."