- The Trump administration has laid out its plans for trade, including tackling NAFTA. American workers have been hurt by trade, but automation has also hurt jobs.

The Trump administration has laid out its plans for trade on the White House website.

The administration says it will tackle trade deals including the North American Free Trade Agreement and the Trans-Pacific Partnership and will push for trade policies that “will be implemented by and for the people and will put America first.”

“Blue-collar towns and cities have watched their factories close and good-paying jobs move overseas, while Americans face a mounting trade deficit and a devastated manufacturing base,” the plan says. “With tough and fair agreements, international trade can be used to grow our economy, return millions of jobs to America’s shores, and revitalize our nation’s suffering communities.

“This strategy starts by withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and making certain that any new trade deals are in the interests of American workers,” the statement continued. “President Trump is committed to renegotiating NAFTA. If our partners refuse a renegotiation that gives American workers a fair deal, then the president will give notice of the United States’ intent to withdraw from NAFTA.”

The administration added that it would "crack down on those nations that violate trade agreements and harm American workers in the process."

Wilbur Ross, the nominee for commerce secretary, said at his confirmation hearing on Wednesday that NAFTA would be an early priority for his department. He said he was "pro-trade," but only as long as it is "sensible trade."

Protectionism has become popular as American workers worry about losing jobs to other countries. And politicians across the political spectrum zeroed in on these anxieties during the 2016 campaign as they vied for the top job in the White House.

Trump made the debate over free trade one of the central topics of his campaign after criticizing China, Mexico, and Japan. He argued in favor of ripping up trade deals, said NAFTA was "the worst trade deal in the history of the country," and called the Trans-Pacific Partnership, or TPP, "a rape of our country."

About 89% of Americans said they thought that the loss of US jobs to China was a somewhat or very serious issue, according to Pew Research statistics cited by Bank of America Merrill Lynch's Ethan Harris and Lisa Berlin. Moreover, only 46% of Americans said they thought NAFTA was good for the economy.

There is some empirical evidence to back up those grievances. In January 2016, the labor economists David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson published a paper showing that increased trade with China did, in fact, cause some problems for US workers.

From the paper's meaty abstract (emphasis ours):

"China's emergence as a great economic power has induced an epochal shift in patterns of world trade. Simultaneously, it has challenged much of the received empirical wisdom about how labor markets adjust to trade shocks. Alongside the heralded consumer benefits of expanded trade are substantial adjustment costs and distributional consequences. ...

"Adjustment in local labor markets is remarkably slow, with wages and labor-force participation rates remaining depressed and unemployment rates remaining elevated for at least a full decade after the China trade shock commences. Exposed workers experience greater job churning and reduced lifetime income.

"At the national level, employment has fallen in US industries more exposed to import competition, as expected, but offsetting employment gains in other industries have yet to materialize."

However, trade is not the only factor that has affected American jobs in general and the manufacturing sector in particular. Automation has also been a contributor.

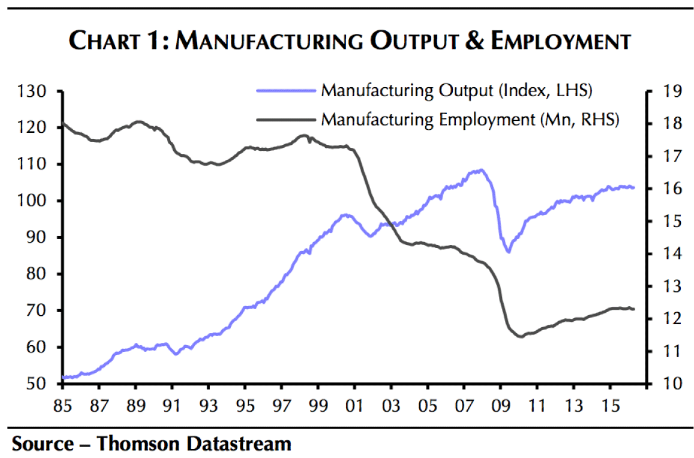

In a recent note to clients, Capital Economics' Andrew Hunter included a chart comparing manufacturing output with manufacturing employment.

Manufacturing employment has been trickling downward since the mid-1980s and started dropping at a faster rate around 2001 - which coincides with China entering the World Trade Organization. Meanwhile, manufacturing output has been increasing since the mid-1980s and is now near its pre-crisis high.

In other words, firms have overall been able to increase output with fewer workers over the years, which is likely at least partially because of automation.

"It's true that many of the manufacturing sectors that account for the bulk of the jobs lost over the past 15 years are also the ones subjected to the most competition from Chinese exports," Hunter wrote. "But US manufacturing has also experienced high productivity growth, with the computers and electronics industry, which has lost the most jobs, seeing the fastest productivity growth of all."

And here's what that could mean going forward, again from Hunter (emphasis ours):

"The upshot is that reversing the five million manufacturing jobs lost since 2001 will be difficult. For a start, if Trump were to pursue protectionist measures targeting China specifically, US firms would simply switch to other low-cost suppliers elsewhere. The only way to eliminate the goods trade deficit would probably involve an all-out global trade war.

"In any case, many of the manufacturing jobs have instead been lost because of faster productivity growth, which can't be reversed. Accordingly, even if Trump were to carry through with his threats of using protectionist policies to try and close the trade deficit, a return of manufacturing employment to 2001 levels is unlikely.

"Furthermore, the damage caused by the kind of blanket tariff on US firms offshoring production, which Trump recently proposed on Twitter, would probably far outweigh any boost to domestic manufacturing employment."

Alexander Kazan, a strategist at Eurasia Group, said in a video for the Eurasia Group Foundation: "From a political perspective, I don't think the focus on trade is misplaced. It's effective because it has an 'other.' It has a competitor or an enemy. People can picture this.

"When you talk about technology, it's much more amorphous. It's this sense that we all lose. So I think politically it's less effective."