Just before Thanksgiving this year, a coalition of meteorologists, climatologists, biologists, ecologists, and other researchers took up a new ritual of thankfulness: tweeting the small and large ways NASA data has helped them understand planet Earth, and attaching the hashtag #ThanksNASA.

For the most part, the scientists avoided mentioning politics or political figures. But context is everything. Bob Walker, a senior adviser to President-elect Donald Trump, had just told The Guardian that the incoming administration planned to strip NASA’s earth science programs of funding.

“We see NASA in an exploration role, in deep space research,” Walker told The Guardian’s Oliver Milman. “Earth-centric science is better placed at other agencies where it is their prime mission.”

In the past, the Guardian story notes, Walker has described earth science as “politically correct environmental monitoring.”

In reality, earth science goes far beyond direct climate change research - and includes everything from the health of oceans to the threat of devastating solar storms in the upper atmosphere.

Dozens of scientists, including the 13 researchers who spoke to Business Insider for this story and many more who reached out on Twitter and by email, said they were rattled and dismayed by the news.

Several said that cutting earth science would represent a radical change from the mission NASA has carried out for nearly six decades.

"If you go to the Space Act that founded NASA in 1958 and then was amended under President Reagan in 1985, the very first responsibility ascribed to NASA is to understand the Earth and the atmosphere," said Waleed Abdalati, who directs the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado and served as chief scientist at NASA from 2011-12.

"It shows up before putting people in space."

Indeed, it does. The beginning of Section 102(c) of the National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958 begins to lay out the role of NASA:

"(c) The aeronautical and space activities of the United States shall be conducted so as to contribute materially to one or more of the following objectives:

"(1) The expansion of human knowledge of phenomena in the atmosphere and space;

"(2) The improvement of the usefulness, performance, speed, safety, and efficiency of aeronautical and space vehicles;

"(3) The development and operation of vehicles capable of carrying instruments, equipment, supplies and living organisms through space."

So far, NASA has carried out that mission with gusto under six Republican administrations and five Democratic ones. The agency's trove of satellite data and analysis is the largest in the world and, critically, available freely on the internet for any scientist or interested person to access.

Some researchers said they didn't recognize how much NASA data they used until it was threatened they could lose it all.

"I started going back and trying to think about what I use in my day-to-day work," said Peter Gleick, a hydrologist who looks at the movement of water all over the world to understand and predict droughts and flooding. "The truth is, I didn't fully comprehend the incredible diversity of products that I use that originated with a NASA satellite or an observing platform or a data archive."

The notion of losing that, researchers told Business Insider, had seemed impossible - that is, until they read the news.

Just days before the Guardian piece with Walker's statement was published, NASA climate scientist Gavin Schmidt, who declined to be interviewed again for this story, told Business Insider that he thought NASA climate research was safe from political tampering because it was too intimately connected to the agency's other critical earth science missions.

It doesn't seem to have occurred to most people that earth science itself might be in jeopardy.

The end of an era?

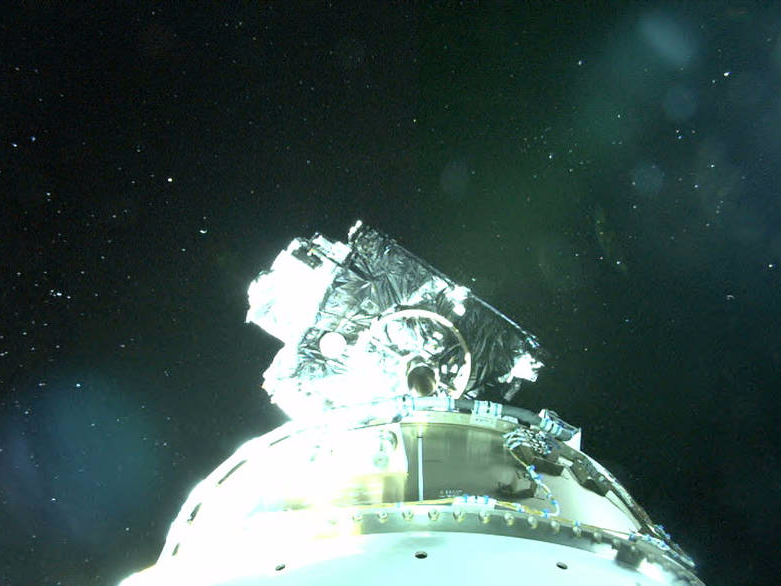

Walker's proposal would ax or redirect more than 34% of NASA's $5.2 billion 2017 science budget request, and almost 10% of its $18 billion overall budget request. This would spell an end to the period that researchers across the world and across a wide range of disciplines refer to simply as "the satellite era" - not the time since Sputnik launched, but the decades of high-quality, consistent, and regular data on the global environment from space.

Marshall Shepherd, who directs the University of Georgia's Department of Atmospheric Sciences and has worked on satellites for NASA in the past, said that the moment a satellite's sensor goes dark without another of the same type to replace it, crucial scientific information will be lost.

An unbroken record is necessary to understand how the past and present fit together, and to make firm judgments about the future.

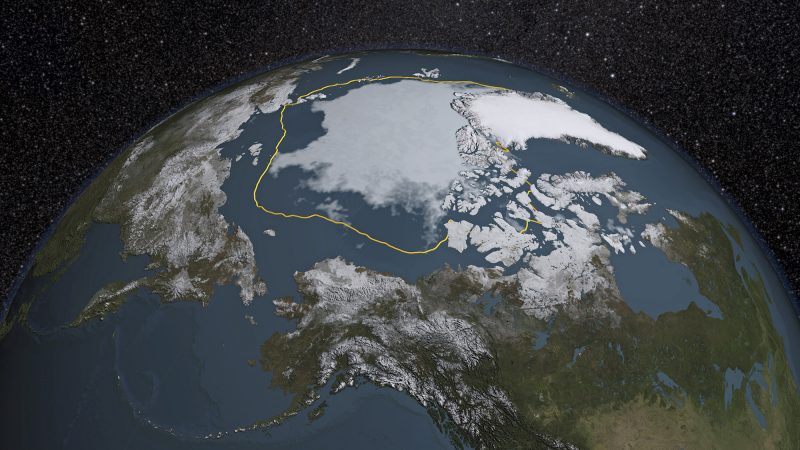

"If you're trying to detect change in something, you need long and continuous uninterrupted records of things like the sea ice or sea level rise or Greenland's ice sheet," Shepherd said. "By shutting those off, you are literally shutting off your long-term record of the diagnostics of the planet."

Julienne Stroeve, a researcher with the National Snow and Ice Data Center, said those gaps would undermine our ability to make even basic judgments about the health of the planet.

"You need the [satellites] to consistently be processed with the same type of sensors over and over again to have a long-term data record, otherwise you have these data gaps and these long-term uncertainties, and you have no idea what the long-term changes really are," she said.

Looking for alternatives

It's all well and good that NASA has the most complete sources of earth science data in the world. But what's really important, researchers said, is how easy it is to access.

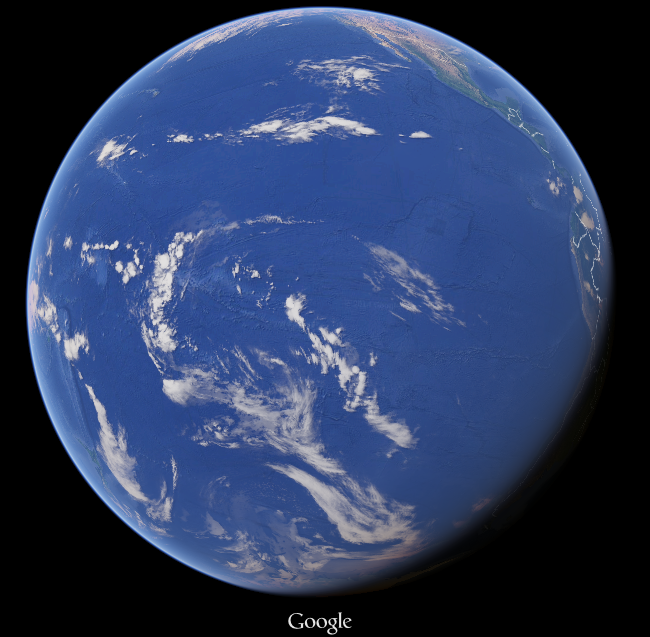

"This is not politically correct to say in Europe, but the US is much better than Europe about sharing data with the whole world," said Jon Saenz, a professor of applied physics at the University of the Basque Country in Spain.

Other agencies tend to tie up their data behind red tape and bureaucracy, Saenz said. He said that if he had to rely on the European Space Agency's limited, difficult-to-access data for his work checking climate model predictions against reality, he'd be "more or less blind" - particularly in the vast, uninhabited stretches of the globe like the Pacific, which are vital for understanding the world climate.

Some scientists said that if the satellite era in their field ended, they would still be able to continue their work. Instead of satellites, they said, they would use a combination of often lower-quality, more difficult-to-access data from satellites operated by other countries and increased data collection at the ground level.

But that can be difficult and even dangerous work, often with much weaker and more uncertain results.

Ulyana Nadia Horodyskyj is a glaciologist who operates a scientific outreach program in Nepal and analyzes lakes that form on melting glaciers high in the Himalayas. If those lakes grow too large or their natural dams become too weak, the dams can burst and flow down-mountain, threatening tens of thousands of lives.

Horodyskyj brings together images and measurements from NASA's Landsat satellites with observations taken on long hikes around the edges of glacial lakes to advise the Nepalese government on how to address the threat.

Without Landsat, "we would be flying blind," she told Business Insider. "We need those eyes in the sky to complement our ground efforts."

Juanita van Zyl is the geographic information system manager at a company called Manstrat in South Africa. She provides information to the South African government and other companies about droughts, wildfires, and grazing conditions in the country. She said she uses data from NASA to help her clients understand where to move resources.

"South Africa isn't a big country," she said. "But when we are in a drought situation like we are in now, the government can only give out so much money out to help subsistence farmers and commercial farmers. Remote sensing is tremendously important in telling them where to send money."

She said the state of the US presidential election in the spring led her to look for ways to build redundancy into her data sources.

"It's scary to think that something might happen and you won't have access to the data anymore," she said.

But - unique among scientists interviewed for this story - the data sets she studies happen to be replicated by a European data set called Copernicus. After some preparation efforts over the course of the last year, she said she's confident that if NASA earth science were to go dark tomorrow, she would be able to keep up a similar level of quality in her work.

No other scientist interviewed for this story said the same.

'Like poking out your eyes while driving your car at high speed'

Some scientists said that without NASA earth science, it would likely be impossible for them to work. Huge swaths of the planet go entirely unmeasured on the ground. Only satellites have the bird's-eye view to place weather events in their full context.

Researchers said that entire fields of study would be left hobbled or unable to function without NASA earth science research and data. Here's a sampling:

Global rainfall

Steve Nesbitt, a researcher at the University of Illinois who works on a NASA mission to measure rainfall all over the world, said that without NASA data, he'd have nothing to study.

He could try to use ground measurements, he said, but it would be nowhere near as sufficient for the scope of his research.

"If you were to try to measure global precipitation on the ground - I mean currently I can fit all of the rain gauges on the globe in the area of about a basketball court," he said.

Farmers rely on Nesbitt and his colleagues' work to measure and model global rainfall to decide how to plant and water their crops. Businesses rely on it to make decisions about production. ("Things like 'How many snow shovels are we going to sell in Buffalo?'" he said.) The US and global transportation systems rely on a deep understanding of atmospheric conditions and long-term weather patterns.

Arctic sea ice

Stroeve, the NSIDC researcher, said that NASA satellites have been necessary to show how dramatically the Arctic has warmed and melted since the 1990s.

"You have one record-low sea-ice year after another," she said. "It doesn't fit long-term trends."

The work Stroeve and her colleagues have done over the span of decades is critical to understanding the radical transformation underway at the top of the world. And there are major economic and diplomatic consequences of those results, as countries and corporations vie for new shipping routes and exposed resources.

She said her work is to observe and report hard numbers on what's happening in the world, and that she finds it baffling that politicians would declare that task political.

The health of oceans

Ajit Subramaniam is a Columbia University professor who tracks microscopic plant life in the ocean.

Those tiny floating life-forms produce up to 40% of the world's oxygen and form the basis of the aquatic food web. Understand them, and you can make judgments about the health of a whole fishery. Satellites can track those microscopic plants by watching how the colors of the sea surface change. And Subramaniam said a satellite can examine in two minutes an area that a ship moving 10 mph would take 11 years to cover.

Without Subramaniam's research, fishers, governments, and conservation groups would lose necessary information about sea life. And deadly algae blooms, an increasingly serious threat to human life along coastlines, would become harder to spot and predict.

Sea level rise

Peter Neff, a glaciologist at the University of Rochester who travels regularly to the Antarctic, said ground observations would never tell you the full story of what's going on with ice sheets in that part of the world.

Unlike Arctic ice, which floats on water, Antarctic ice sits on land. If those ice sheets were to collapse, global sea levels could change dramatically.

On the surface, Antarctica's ice still looks pretty still and stable. But ice-penetrating NASA satellites and airplane-mounted sensors show that far below the surface, some are melting at a rate of hundreds of meters a year and risking collapse.

"We never thought these kinds of changes happen year to year," Neff said. "It's dumbfounding how much data NASA produces and how quickly they release it. They fly over an area and the next day the data is available."

Neff's research helps us understand the health of massive glaciers with behavior we still don't fully understand but that lock up enough water to drive up global sea levels on the order of meters, not inches.

And none of them would be able to do their work without NASA satellite data.

Other agencies can't pick up the slack

Walker, Trump's adviser who wants to shutter NASA earth science, told The Guardian that other US agencies would be able to pick up where NASA leaves off.

"My guess is that it would be difficult to stop all ongoing NASA programs," he said. "But future programs should definitely be placed with other agencies. I believe that climate research is necessary, but it has been heavily politicized, which has undermined a lot of the work that researchers have been doing. Mr. Trump's decisions will be based upon solid science, not politicized science."

However, researchers familiar with US science initiatives said such a move wouldn't be feasible without massive expenses or losses in capability.

"You can't just send money over to another agency and expect them to be able to launch satellites," said Abdalati, the former NASA chief scientist. "There's an expertise that exists within NASA that isn't particularly portable. But if it were deemed necessary that the capability to go to some other agency, they'd have to move a lot more than the money."

Shepherd said that the problem has to do with the way institutions like NASA work.

"By shutting off NASA's earth sciences program, you are shutting off expertise, institutional knowledge of the Earth's system that cannot just be spun back up," he said. "It's not like training someone to cook burgers in a fast-food joint. You're talking about years and decades of expertise and technical knowledge. Brainware will be lost, and that is critical."

Another problem is that NASA earth science is more than people - it's buildings, systems, and machines that are now woven into the framework of the space agency and could not cheaply or efficiently be extracted.

"They'd have to move the people, they'd have to move the systems, the infrastructure, the facilities. And, you know, it currently exists in the framework that supports all the space activities, so to carve out the Earth piece would be inefficient because you would have to build capability twice," said Abdalati.

Another problem is that there isn't another agency within the federal government built for NASA's task.

The closest is probably the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which is responsible for the day-to-day tasks of government weather forecasting.

"Certainly NOAA is an organization that provides lifesaving forecasts," Nesbitt said. "I don't want to take anything from NOAA. But they have a different mission and rely on NASA to launch satellites."

The problem, he said, is that NOAA isn't structured for the high-risk, boundary-pushing work NASA does every day.

"It's kind of like if you have a car. Want to fix it? Go to a mechanic (like NOAA). If you want to take it in an auto race, go to someone who is more experimental, and that is NASA. They can develop something that is amazing. It may not work every single day, but then they can scramble and fix things," Nesbitt said. "There's just that cultural divide, and I'm worried that if they take these experimental missions and plug them into NOAA, there's going to be harsh degradation."

A threat to national security?

NASA's earth science program, several researchers said, is critical to national security.

There are the obvious ways: building and constantly improving the infrastructure necessary to predict hurricanes and other extreme weather, collecting images of disasters to guide emergency response workers, and tracking sea level changes around the world that affect coastlines and the Navy.

But plenty are less obvious - but no less important - ways NASA helps keep the country safe.

In September, Business Insider published a story about the severe and underreported danger that space weather poses to modern society. There's a very real threat that a major solar storm could strike Earth and knock out the electric grid, satellites, navigation systems on airplanes, and any other electrical system not hardened to withstand the blast.

These sorts of events aren't all that rare - the last one happened in 1859.

"We'll almost certainly see a major event in our lifetimes," said Morris Cohen, a researcher who studies electrical events in the upper atmosphere. "It's kind of a game of Russian roulette we're playing. Keep playing forever, and eventually you're going to get hit."

If scientists are on alert, humanity should have a few days to prepare between the start of a solar storm and the moment it reaches Earth, Cohen said. But that prediction will rely on NASA earth science mission data.

"Obviously what's driving the political question of 'Yes to earth science or no to earth science?' is climate change," Cohen said. "That's the motivation behind cutting all this stuff. But what a lot of people don't realize is that earth science data and earth science in general goes way beyond climate change. The same satellite that's capturing data from clouds is also capturing data about what's going on in space and what's coming from the sun."

Cohen said he's working on a project to strengthen the US military that would be impossible without geoscience research of the sort that's threatened at NASA.

Right now, the military relies on satellite GPS systems for navigation, just like civilians. But GPS is remarkably easy to jam. Cohen has worked on an alternative system that would use live data on lightning strikes and the radio waves they emit to build a more resilient navigation system for the military that would be much more difficult to disrupt.

Without geoscience research, he said, the system would never get off the ground.

Researchers resist the idea that their work is political

Jacquelyn Gill researches paleoecology and plant ecology - in other words, she studies the history of the global climate over millions of years - at the University of Maine.

She and her students spend their time trying to understand how the atmosphere worked in the ancient world - sometimes finding themselves knee-deep in bogs collecting buried pollen or ash from ancient fires.

"Despite our best efforts, all we see of the Earth's climate is a really narrow snapshot in time," she said. "And to get a more complete and full picture of how Earth operates, we need long-term data."

That long-term data shows that modern climate change is faster and more acute than anything else in Earth's history. But there are also concrete implications for modern-day lobster fishers - and for futuristic endeavors like terraforming Mars.

And none of it would be possible, she said, without NASA data creating a baseline for how the climate works.

"A lot of the work we do in the past is motivated by the world we have in the present," Gill said. "If we don't have that information then [the past data] becomes a kind of novelty. It loses its grounding."

Without NASA's earth science programs, many researchers say they expect to see the American scientific enterprise to become less singular and less great, and to fall into decline.

"It's unfortunate that the politics of climate change have evolved to the point in this country where really serious games of chicken are being played with major agencies in our federal government," Nesbitt said. "These are agencies that have absolutely no political agenda, just collections of scientists that are doing work to better society. And it's really sad that these political forces are trying to exploit this issue."

"Is there a line you can draw between understanding how the Earth works and the so-called politically incorrect environmental monitoring?" Subramaniam said. "If you think of the Earth as a being, knowing how well it's doing is a good thing is how I see it. Why would we not want to do it?

"It's a head-scratcher for me. I simply don't understand what the issue would be."

Giving up on part of what makes us human

Chanda Hsu Prescod-Weinstein is an early-universe cosmologist. That means she works on understanding what happened in the moments after the Big Bang, when the whole universe was hot and physics was bent to the point of breaking.

Her work relies on data from NASA's spaceward missions, and a shift from earth science toward even more space data might offer new opportunities for her research. But she said the idea of a NASA that no longer examines the Earth scares her.

"You know, I am not a parent, but I have a niece who just turned 8, and many of my close friends have children right now. And I want those children to have a beautiful life," she said. "I think that trumps any interest in early-universe cosmology. The work that I do on dark matter, I'm not sure it will have a lot of meaning if those kids don't have an opportunity to learn about it because society has been devastated by global warming. So that's, for me, the priority."

Abdalati said that losing half of NASA's mission would mean giving up on part of what makes us human.

"As human beings, throughout time, we have explored our surroundings, and we have worked to understand our environment, and we looked as far beyond as we could," he said.

And NASA fulfills both drives - to understand and to explore.

"I think both are critical. Both are essential. I wouldn't want to see human space zeroed out to support a whole bunch of earth science" either, he added. "I may differ from some of my colleagues in that, but I think we need it all."

Lori Janjigian contributed to this story.

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that Walker's proposal would ax or redirect 40% of NASA's budget and operations. This was based on past numbers, and referred only to NASA's science budget, not the agency's total budget. In fact, Walker's proposal would ax or redirect more than 34% of NASA's $5.2 billion 2017 science budget request, and almost 10% of its $18 billion overall budget request. Thanks to Loren Grush of The Verge for spotting the error.