Republicans have made a big decision about the future of your online data – and many people aren’t happy about it.

On March 28, Congress voted along party lines to kill a set of rules adopted by the Federal Communications Commission in October that would’ve forced your internet service provider, or ISP, to ask you before it collected certain personal information. In both chambers, most Republicans voted to repeal the rules, while Democrats voted against.

The joint resolution that enacts those changes, S.J. Res. 34, was presented by Republican Sen. Jeff Flake of Arizona and cosponsored by 24 other Republicans.

President Donald Trump signed the resolution on Monday night, turning it into law.

So does this mean your ISP now has free rein over everything you do online? Yes and no. But the rollback could also lead to a more fundamental change in how the internet is run. Here’s a rundown of what’s happened and what it means for you.

Read on to learn how the repeal of the FCC's privacy rules will affect you - or jump ahead to see:

- How we got here. Arguments from both sides of the debate. If your ISP can see/sell everything about you. What ISPs are saying about how they'll approach privacy. How ISPs could approach your data like Google and Facebook. What you can do to keep your data private. How net neutrality could be affected. If other laws can be made around privacy.

How did all of this get started?

Let's take a step back. An internet service provider, or ISP, is a company that, well, provides internet service. ISPs include firms that sell internet access for your phone (Verizon, AT&T, T-Mobile, Sprint) or your home (Verizon, AT&T, Comcast, Charter, etc.).

In the early 2000s, the US government classified these companies as "information service providers." That meant they were subject to rules set under Title I of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which broadly decides how telecommunications companies are governed.

As the internet market progressed, though, many liberals and Democrats in Washington became increasingly concerned with what they saw as the potential anticompetitive behavior of those ISPs. This led a fierce argument over "net neutrality," or the idea that ISPs should be legally required to treat all traffic equally instead of playing favorites for financial gain.

Democrats tried on multiple occasions to enforce net-neutrality principles for ISPs, but each time, their attempts were shot down because ISPs were classified under Title I. The surest way to make net-neutrality laws legally enforceable, they said, was to reclassify ISPs as "telecommunication providers" using Title II of the Telecommunications Act.

So in 2015, after years of fiery debate, the Democrat-led FCC did just that. It then set in place the 2015 Open Internet Order, which forces ISPs not to block, throttle, or prioritize the speeds of websites as they see fit. It, in essence, treats the internet as a public utility - that is, something everyone in America needs, like electricity or running water.

The 2015 Open Internet Order also aggravated many Republican members of Congress and the FCC. They said (and continue to say) the internet was not broken to the point where such laws were necessary, and that Title II would slow down what should be a fast-moving, mostly free market.

Opponents also argued that reclassifying ISPs under Title II put those ISPs under far greater regulatory pressure and oversight than they had under Title I. In other words, the FCC gained significantly more power over what ISPs could and could not do.

Which brings us, finally, to the privacy debate that has transpired.

One of the things the FCC gained with its newfound power was, in effect, authority over ISPs' privacy policies.

Before the Title II reclassification, the Federal Trade Commission, or FTC, looked over those policies. But by law, the FTC cannot regulate "common carriers," which, put simply, is another term for companies that provide a utility service. And the internet is now considered a utility after the 2015 Open Internet Order. With that in place, ISPs are common carriers, so their internet-privacy policies are exempt from FTC oversight.

This created a gap of sorts in regulation. To fill it, the FCC set about creating a set of privacy rules specifically for ISPs.

Many of those rules took after the guidelines recommended by the FTC before the Title II reclassification. ISPs would've been free to use some "nonsensitive" personal data, like email addresses, for advertising purposes without having to ask customers beforehand, but they'd have had to give those customers the ability to opt out of that practice.

With other "sensitive" personal data - like Social Security numbers, children's info, financial info, health info, and location data - the FCC would've forced ISPs to give customers the chance of opting in before an ISP could collect the data.

Again, this is same recommendation - but not mandate - presented in the FTC's privacy guidelines.

However, the FCC's privacy rules notably excepted from the "sensitive" category data about web browsing and app usage. The rules would've forced ISPs, and only ISPs, to let customers choose whether to opt in before they could share that data with advertisers and other third parties. This is the main difference between the FCC's rules and the FTC's guidelines.

It also outraged the ISPs, some of which are interested in making a bigger play in the digital-advertising business. Verizon, in particular, spent billions on AOL and Yahoo to do just that.

But the non-ISP companies it competes with in that space, namely Google and Facebook, still have to follow only the FTC's privacy guidelines.

That means they can collect data that shows what sites their users browse and what apps they use without having to ask for permission first. In turn, they have less of a chance of their users opting out and, therefore, losing revenue.

So, in many ways, this whole thing was a question of default settings.

When ISPs say they want to be regulated under the same FTC guidelines as Google and Facebook, what they mean is they want their data targeting to be opt-out by default - and that they don't think data about web browsing and app usage is "sensitive" info. People are less likely to turn off a privacy setting if they have to go out of their way to do it.

The good news for ISPs is that they may now have even more freedom than Google and Facebook, but we'll get to that in a bit.

In any case, it's crucial to note that the FCC's "opt in" provision had not taken effect yet. It wasn't scheduled to until early December. So the rollback didn't take away any rights you had. It's more about ensuring the status quo - and letting ISPs move forward with their advertising ambitions - for the foreseeable future.

Many Republicans fell on the side of the ISPs.

Many in the GOP argued it was unfair to create different sets of privacy regulations for ISPs and "edge providers" - internet-based companies like Google and Facebook that provide services on the ISPs' networks.

They said the FTC's privacy framework had sufficiently protected user privacy over the years. They ultimately want all privacy regulations of ISPs to return to the FTC, but for now, they say any FCC privacy policies should follow the FTC's framework, which could create more competition in a digital-advertising market where Google and Facebook are by far the two most dominant players in the country.

Meanwhile, many Democrats said any imbalance was justified.

Democrats argued that an ISP had the potential to see and collect more about you than an edge provider did. You can simply disable location services with an app, for example, but a mobile ISP can always see where phones are connected to its cell towers.

They also argued you had greater choice in using different websites than in using different ISPs. It'd be impractical, but if you really wanted to get around Google and Facebook's footprint, you could. But in many places, particularly in rural America, there isn't much choice in ISPs. According to the FCC's latest Internet Access Services report, for example, only 24% of developed housing areas had at least two ISPs that offered official broadband speeds.

Democrats also noted the difference in business models. With Google and Facebook, there is an implicit handshake that their ad policies are how you "pay" for their sites and apps, most of which are free. If an ISP practices the same policies, though, it's double-dipping - charging you monthly for internet service and collecting your data for ad dollars.

Nevertheless, the resolution is now law. And the way Republicans passed it is important.

They used a tool called the Congressional Review Act - CRA, if you can handle another acronym - which the GOP is using en masse to repeal federal regulations passed late in the Obama administration. It allows lawmakers to do so with a simple majority vote.

Beyond providing the ability to repeal regulations, though, the CRA prohibits those federal agencies from ever making "substantially similar" rules again. How far that'd go in court is unclear, but now that Trump has signed S.J. Res. 34 into law, the FCC cannot ever make another set of rules that makes ISPs follow the same privacy guidelines it adopted last year.

At the same time, the FCC will remain in charge of ISPs' privacy policies. That's because the 2015 net-neutrality order still classifies ISPs as common carriers - a fact many Republicans loathe - and the FTC is still prohibited from regulating those.

Does this mean my ISP can just see and sell everything about me?

Not quite. But to be clear, this is a glorious result for ISPs like Verizon and Comcast that are banking on digital advertising being a big new revenue stream.

They have a treasure trove of user data that advertisers would love to see. They know your name and where you are, they could track what places you visit on the road, and they can see every site you visit over their network. Much of this data is stuff they need to provide you with internet service in the first place.

Pair that with the amount of content these ISPs are buying, and you have the makings of some immense businesses.

Last week, Bloomberg reported that Verizon was working on a live-TV streaming service similar to Sling TV.

Let's say it's good. That creates a scenario where you could pay a monthly fee for Verizon's mobile internet; pay another fee for its FiOS home internet and/or cable service; pay another fee for its live-TV service; watch a bunch of ad-supported videos on AOL or Yahoo or Oath (or, in a different life, go90); and implicitly pay the company through its beefed-up, deregulated ad network.

Those ads could be super-personalized because the ISP can follow every URL you visit on its network and, especially if you stream its video apps, identify the kind of content you like. This would ostensibly make you more likely to click the ads, thus attracting a bigger premium for Verizon's ad space.

Now let's say the net-neutrality order is repealed and Verizon can charge companies for faster internet access on its network (while exempting its services - it is allowed to do that now).

There are a lot of hypotheticals in that, per usual with this line of argument, but it's not that far from being a reality.

All that said, the data ISPs can collect isn't omnipotent.

The FCC still has authority over ISPs' privacy practices. While it now cannot enforce the Obama-era privacy rules, it can still regulate particularly unjust violations of privacy by ISPs on a case-by-case basis via the Communications Act, the 1930s-era (!) set of laws upon which the Telecommunications Act is based.

So, for example, your ISP can't take your browsing history, tie it to your name, address, and Social Security number, then sell that package to the highest bidder. No amount of angry fundraising will let you buy Congress' internet data.

Aside from being asinine business, that would violate Title II Section 222 of the Communications Act, which says common carriers cannot permit access to "individually identifiable" customer data except in a few specific instances, like when required by law.

The FCC has punished ISPs for data-tracking policies it has found unreasonable. Last year, for example, it went after Verizon for inserting advanced ad-tracking "supercookies" into its users' mobile traffic without their consent.

It fined the company $1.35 million and applied a three-year compliance plan that requires Verizon to obtain opt-in consent before sharing that "supercookie" data with third-party advertisers and, more leniently, to provide an ability to opt out when using that data for its ad networks. That compliance plan is still in place.

If you take them at their word, groups representing the big ISPs pledged in January that if the Obama privacy rules were killed, they'd voluntarily follow privacy guidelines that mostly take after the FTC's framework.

In a notice sent through one of their biggest trade groups, the CTIA, the ISPs said they'd "follow the FTC's guidance regarding opt-in consent" for "sensitive information as defined by the FTC."

That, in all likelihood, means they'll ask for consent before sharing your location data, children's info, health info, and so on with advertisers.

What the CTIA did not say it would make opt-in by default, though, is your data about web browsing and app usage.

In March, the CTIA argued in a petition to the FCC that such data wasn't "sensitive." Nothing in the Communications Act says anything about that either.

Instead, the CTIA's January notice says the ISPs will let you opt out of policies that collect that and other "nonsensitive" customer data for third-party marketing.

For first-party marketing, the CTIA's letter says only that it will rely on "implied consent" to use customer data. This suggests that when data tracking is used for an ISPs services or ads, it may not give you a choice to opt in or out and instead assume that because you are using its service, you're OK with it collecting that data.

This isn't particularly new or surprising, but the larger point is that you may have to take ISPs at their word now.

Yes, the FCC has punished intrusive ad-tracking without strong privacy regulations in place, but that was under the previous chairman, Tom Wheeler, who had an unusually critical eye about ISPs' activities.

But the current chairman, Ajit Pai, is Wheeler's polar opposite: extremely hands-off and a proponent of ending Title II regulation of ISPs.

"One of the big questions will be whether the FCC decides to enforce some of these restrictions," said Julie Brill, cohead of the privacy firm Hogan Lovells and an FTC commissioner under Barack Obama. "That's going to be up to the commissioners and the staff to decide how and whether they move forward in the event that the ISPs do anything inappropriate."

What do the ISPs say about how they'll approach privacy?

We asked Verizon, AT&T, Sprint, Comcast, T-Mobile, and Charter to clarify how they'd go about their privacy policies after the repeal.

Comcast, T-Mobile, and Charter did not reply to requests for comment. The other three referred us to the CTIA - instructive in Sprint's case, since it's not formally listed on the January notice - and Verizon and Sprint linked us to their current privacy policies.

Sprint's main mobile-advertising program is opt-in. Most programs on Verizon's page are opt-out, while others are opt-in. Charter and T-Mobile both provide the ability to opt out of their targeted ad programs as well.

Comcast also pointed to the CTIA's notice in a blog post on Friday, reaffirming that it would let customers opt out of sharing their web-browsing history in the process. The company said it would continue to let customers opt out of receiving targeted ads, too, and that it wouldn't sell a customer's "individual browsing history" to third parties.

Ars Technica notes, though, that Comcast still runs its ad network. It sells targeted ads for other businesses and uses the data it has on its customers to better reach those ads' potential audience. So you're still likely to see targeted ads, but in this case, Comcast has some incentive not to share its users' history, since its ad business depends on outside advertisers needing Comcast to best serve their ads.

AT&T also published a blog post on Friday touting its privacy policy and said it would "not sell your personal information to anyone, for any purpose. Period." What the company defines as "personal information," though, is slightly vague. When asked to clarify, an AT&T representative pointed to the company's privacy-policy FAQ page.

There, AT&T defines it as "information that directly identifies or reasonably can be used to figure out the identity of a customer or user," like a name, address, phone number, or email address. So it wouldn't tell advertisers outright that I'm Jeff Dunn, for instance - which it probably cannot legally do.

But the company leaves the door open for sharing "anonymous information," which it calls info that cannot "reasonably be used" to identify you directly. It also doesn't say anything about not sharing "aggregate information" in which it lumps customer data into anonymized groups.

Verizon in a statement on Friday made it clear that it would do the same. The company reiterated it would not share directly identifiable info with advertisers, but it would still collect personal data then de-identify or aggregate it before selling it for targeted-ad purposes.

Comcast did not reply to a request to specify what it defines as "individual browsing history."

In each case, though, it's unclear if data about web browsing and app usage would fall under "personal" or "anonymous." But given that the CTIA's letter deems such data as "nonsensitive," just as the FTC does, it's likely to be the latter.

Learning about the privacy policy of your ISP usually means finding the policy, doing a good chunk of scrolling and reading to figure out what the ISP is doing, and, sometimes, calling the ISP to decide how you want your data treated. In the future, you may have to wait and look out for whatever policy updates it makes, though AT&T is promising to notify customers in advance of any revisions.

This was part of the point of ISPs' cries against the opt-in mandate for browsing data - many people just won't go through this much trouble to stop ISPs from taking the data they want. You can lament this laziness all you want, but there's a reason this has become a national issue. That lack of motivation is money.

So will ISPs do anything different than Google and Facebook?

Possibly. But ISPs could face advantages and disadvantages in the digital-ad market.

Given their pledges to follow the FTC's guidelines, ISPs are likely to approach your data the way Google and Facebook do.

Chances are they'll make a profile of you that won't use your name but will give you a random, anonymous identifier, then collect your location, browsing history, app-usage data, gender, and probably other demographic info.

ISPs could then sell those profiles to advertisers. Those advertisers could plug that info into computerized programs that could put personalized ads on the apps and webpages you visit. The ISPs aren't selling you so much as they're selling targeting, monetizing the gobs of info they have on their customers' habits.

For example, let's say I frequently visit websites about the Red Sox and use MLB's streaming app all the time. If I don't opt out of its data-collection policies, my ISP could signify my traffic is coming from a mid-20s man who is in New Jersey and likes baseball.

The ISP could then make money by helping some advertiser's algorithms understand that they have a better chance of getting my attention by serving up, say, an ad for tickets to upcoming baseball games. All of this happens within seconds.

The advertiser doesn't know I'm Jeff Dunn, but it can get a good idea of my online interests since my ISP can see wherever I go on its network.

You've seen this before. It's called behavioral targeting, and Google, Facebook, and others make lots of money off it today. What's new is the sheer amount of data an ISP could see compared with those companies, and thus the level of personalization they could achieve.

Remember that "supercookie" tiff? What Verizon did there was stick its customers with unique identifiers on a network level. It was able to track your habits - and share that data with advertisers - anytime you used its network, wherever you went online. You can opt out now, but before, there was effectively no way to dissociate yourself from the tracking.

Theoretically, the fact that an ISP controls a network gives it the ability to reach further than an internet company could. For instance, because it can see your location when you're connected to its network, it could better see the effectiveness of targeted ads. It could more easily tell if I went to Yankee Stadium after seeing that ad about baseball tickets.

Google's apps need permission to see where I am; an ISP knows it by default. If they were to build out their ad networks further - and if they could get people watching their content services, which will be zero-rated - ISPs ostensibly would have the most powerful tools for advertisers.

You'll notice I keep using qualifiers like "could" and "theoretically," though. Aside from some ISPs' promises not to sell personal info, any advantage those ISPs have with data collection isn't that much greater right now than what Google and Facebook have.

Those two have already built massive ad and content networks that, practically speaking, are difficult for a denizen of the internet to escape. According to Nielsen, Facebook and Google ran the eight most popular apps in the country in 2016.

And stepping outside of their ad networks isn't as simple as just not visiting Google- or Facebook-owned websites. They can't reach everywhere the way an ISP could, but they have tracking codes on many major sites.

Google Analytics, for instance, is used by numerous companies to track people who visit their sites. Facebook has also been found to buy personal, offline information - like loan history - from data brokers to target its ads further. If the two aren't a duopoly in digital advertising, they're at least something close to it.

Beyond that, more and more websites are getting encrypted. If you see an HTTPS in front of a site's URL, it's using a secure layer on top of the standard HTTP web protocol.

It also means an ISP cannot see exactly what you visit beyond the base URL of that site. An ISP could know that you visit WhiteHouse.gov, for instance, but it couldn't see if you visited, say, the Legislation page of the site.

The ISP can still glean a good amount by seeing every site you visit in the first place - and that encryption won't matter much if the ISP runs the site you're visiting - but it provides you some sort of buffer.

However, this isn't entirely foolproof. There are techniques to get more specifics about what people are searching, and the Department of Homeland Security has discovered tools that can weaken the security of the encryption.

Meanwhile, the trade-off for Google's and Facebook's services being free is that you let them more easily see the things you do on those sites. And because many of those sites are popular, they can suss out a good chunk of personal info that could be used for ad purposes. You can see why some ISPs are so eager to build content businesses.

According to Brian Wieser, a senior advertising analyst at Pivotal Research Group, this should keep Google and Facebook from feeling too threatened in the online-ad industry.

"Importantly, Google and Facebook have different kinds of data, and potentially more valuable data," Wieser said. "Google has 'intent' data from searching histories. It also knows what kinds of YouTube videos a consumer watches. An ISP will not have this data. Facebook knows what your personal attributes are based on what you have provided Facebook with, and also based on who is in your social network. An ISP will not have this data. Both are better positioned with respect to cross-device-based data, as consumers can be logged in across devices."

That last bit is also significant. Saying an ISP can see everything you do makes sense when you're on its network.

If, say, you subscribe to T-Mobile for phone service and Comcast for home internet, the two wouldn't cross - Comcast couldn't see what you do over mobile data, and T-Mobile couldn't see what you do on your home Wi-Fi. Companies like Verizon and AT&T that offer both are in a better position, but that's not guaranteed either.

These are all speed bumps that Google and Facebook can more readily circumvent since their services and ad networks are popular across device types.

But again, the rollback potentially not giving ISPs as big of a business advantage doesn't do much to keep your data private. While they may not share your most outright personal info, they can get close, just as Google and Facebook can today.

More importantly, the ball is in effectively in their court when it comes to their ability to collect that data in the first place. That separation between home and mobile internet may also change as 5G becomes prominent and mobile ISPs make a bigger play for the home.

Also worth noting: Google and Facebook are happy about this.

Although the FCC's privacy rules didn't apply to them, internet companies like Google and Facebook are still breathing a sigh of relief that they're off the books. Yes, it means they have some newly empowered competition, but their trade groups asked Congress earlier this year to kill the rules all the same.

What they feared was the precedent the Obama-era rules could've set. If ISPs were the only ones that had to ask customers for permission before they chomped up data about web browsing and app usage, they probably would've made a stink about it.

It doesn't take much to see how that could have led to rules that would level the playing field again - only, in that case, it would've had the side effect of bolstering online privacy on all sides.

That's really the big loss for privacy-conscious consumers — the FCC's privacy rules could've set a legally enforceable baseline for how all tech companies collect your data.

Instead, Trump and the GOP have effectively decided that far-reaching data collection and more targeted ads should be the norm. You'll still be able to opt out of the creepy stuff, it seems, but the rollback de-prioritizes online privacy as a concept.

If you don't want big tech companies to peek at and sell what you do online - in whatever form - you have to go out of your way to change it. And because the resolution uses the CRA, it's probably going to stay that way for a good while.

Is there anything I can do now to keep my data private?

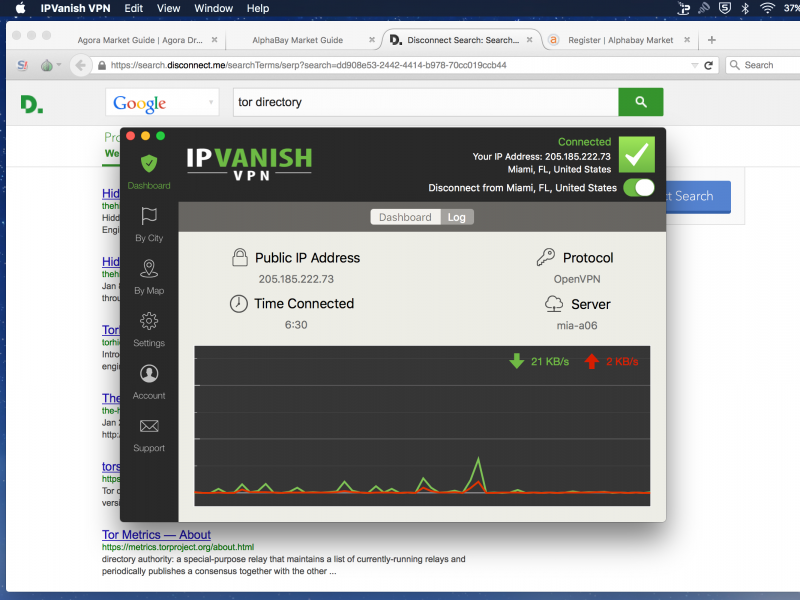

Yes, but none of the solutions is perfect. We've noted the slight benefits of using encrypted sites, but the most common suggestion is to use a virtual private network, or VPN. These are services that allow you to run your internet connection through another company's remote server.

They can hide whatever you do over that connection from an ISP - and are often used to get around regional blackout policies for certain streams - but they're usually slower, and setting them up is a process.

Plus, it's not hiding your data completely - you're just shifting your trust from your ISP to the company running the VPN. And while there are tons of free VPN services, they can't all be trusted. For something worthwhile, you have to pay another monthly fee.

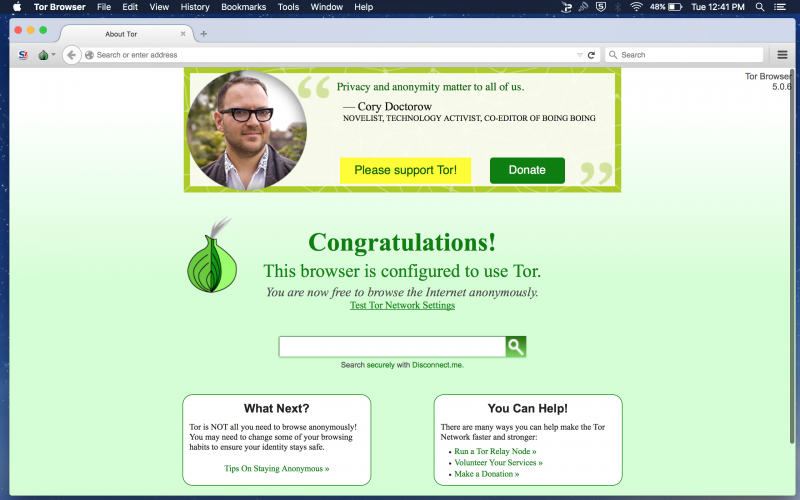

Alternatively, you could try using the Tor browser, which aims to anonymize the traffic of its users. But it's not foolproof, and it's notably slower than Chrome or Safari. This, again, is what's most disheartening for consumers - to ensure your privacy on the internet, you have to accept a lower-quality experience or pay extra.

It's not out of the question for ISPs to try monetizing "enhanced" privacy protections either.

"We anticipate the return of 'pay-for-privacy,'" Fatemeh Khatibloo, a principal analyst at Forrester, said in an email. That is, "tiered pricing models that would effectively make privacy a privilege for those who could afford to pay more for these services every month."

AT&T did something like this with its now defunct Internet Preferences program for its GigaPower broadband service. That made its entry-level plan cheaper but in return scanned its customers' web-browsing data to serve up targeted ads. It more or less necessitated a VPN to avoid having your data collected. To get a plan without Internet Preferences, you had to pay at least another $29 a month. AT&T shuttered the whole thing last fall.

Whether any ISP brings back a similar service is pure speculation for now, but the lack of clear legal barriers to it would seem to at least open the door.

There's no mention of these kinds of programs in the CTIA's letter from January, and none of the major ISPs we asked about the possibility of enacting such programs would comment on the matter directly.

Does this affect net neutrality?

Potentially, very much so.

Pai and the GOP ultimately want to return privacy regulation of internet providers to the FTC. But the FTC cannot govern the privacy policies of ISPs so long as they are "common carriers" under the Title II classification.

The Title II classification is what gives the FCC the ability to legally enforce the current net-neutrality rules, though. And now it's unclear if the FCC could ever impose new privacy regulations on ISPs again.

Complicating this is an appeals court decision from last year that said the FTC could not regulate common carriers in any field, be it for their common-carrier business (i.e., providing internet or telephone service) or anything else.

Republican Rep. Bob Latta of Ohio has said he plans to introduce legislation that would get around that ruling, but that wouldn't change the fact that Title II and the FTC having privacy jurisdiction over ISPs are incompatible.

All of this is to say that an attack on the 2015 Open Internet Order is coming into the crosshairs next. White House press secretary Sean Spicer said as much last week, and Pai seems ready to act as well.

"We need to put America's most experienced and expert privacy cop back on the beat," Pai said in a statement on Monday, alluding to the FTC. "And we need to end the uncertainty and confusion that was created in 2015 when the FCC intruded in this space."

How exactly Pai or the GOP would go about repealing the net-neutrality rules is unclear. Those were created long enough ago to be untouchable by the CRA. That means Republicans would need to get some Democrats on the side of whatever rules it proposes. Considering that not one Democrat voted in favor of rolling back the Obama-era privacy rules, though, that could be a hard sell.

Pai could try to make a more direct change through the FCC, but then he'd have to prove that the Title II reclassification had done enough damage to ISPs to warrant its reversal, since the order was upheld in court last year.

Based on his recent statements, Pai's likely line of attack will be to say that Title II has created too much "uncertainty" for internet providers, thus harming their willingness to invest in new networks.

But, while ISPs' spending on network infrastructure has declined slightly since 2015, it's hard to say that's a direct result of Title II. The industry is in a time of transition anyway as it prepares to roll out 5G tech, and in some cases, investment has increased over the past two years.

Can any other laws be made for the privacy rules specifically?

Congress could create the consistent framework many Republicans want by creating a set of rules for how ISPs and internet companies treat customer data, but given the GOP's repeated desire to return privacy regulation to the FTC, though, that seems unlikely.

Pai has said he wants to create a privacy framework for ISPs that effectively puts them back in line with the FTC rules that govern Google, Facebook, and the like. How far he could go in doing that after the CRA is unclear, though. Since the sections of the Communications Act that allow the FCC to review privacy policies make no mention of data about web browsing and app usage, those provisions likely could not be made opt-in by default.

Where things might get complicated for ISPs is on a state level. The New York Times reported last week that a handful of states had started considering legislation that would require ISPs to get opt-in consent before sharing web-browsing, app-usage, and other personal information. One such bill has been approved by Minnesota's House and Senate already.

If things like this get far enough, it could pressure more ISPs into making opting in the norm across the country to avoid a headache.

Throughout it all, though, the biggest concern is the one that drives most internet-regulation debates: There just isn't much competition among ISPs.

The rollback of privacy rules wouldn't be as big of a deal to people if they had a choice between an ISP that collects data en masse and one that makes it a point not to serve up targeted ads. But in wide swaths of the country, that choice does not exist, particularly when it comes to wired internet.

It's the same deal when it comes to the net-neutrality debate.

Without other companies to push them or a federal body to provide them clear privacy rules, there isn't much incentive for ISPs to make life harder for themselves. You could say the new ad revenue would help ISPs lower the prices of their core services, but that assumes they'd have a competitor giving them a reason to do so.

We will have to wait to see how ISPs go about their privacy policies without the Obama-era rules hanging over them - the thing is, that's all you can really do right now.