- The effects of the Tonga volcano eruption reached space, according to NASA satellite data.

- The eruption spurred hurricane-speed winds and unusual electric currents in the upper reaches of Earth's atmosphere.

- Researchers said it was one of the largest disturbances in space in modern history.

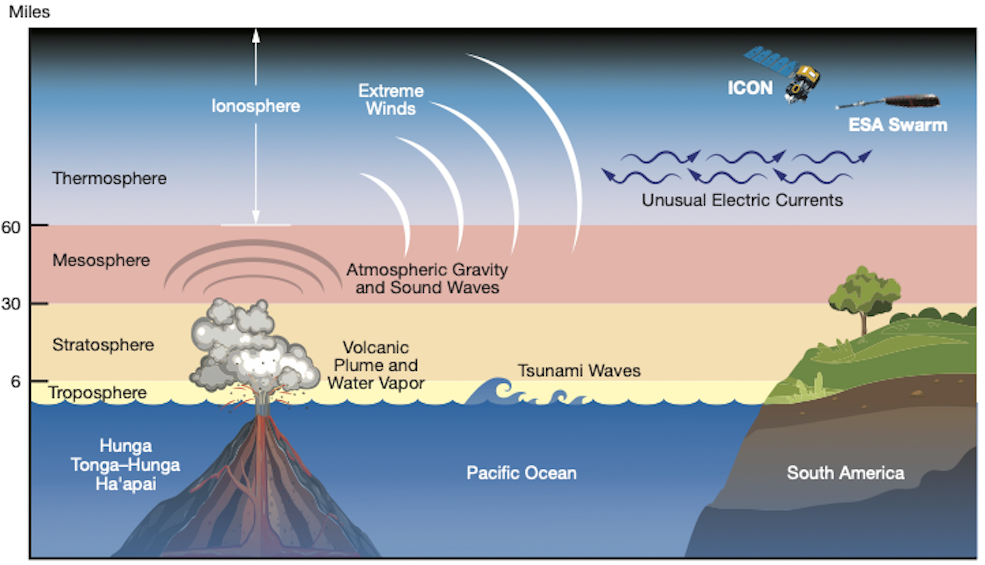

When an underwater volcano erupted on January 15 near the Pacific island nation of Tonga, it sent massive shock waves and fast-moving tsunamis around the world. Now, scientists are beginning to understand just how big the Tonga volcano's blast was.

Not only did the eruption cover much of Tonga in a plume of ash, destroying homes and triggering a tsunami that killed at least three people — it reached the edge of space, according to newly released NASA satellite data. "The volcano created one of the largest disturbances in space we've seen in the modern era," Brian Harding, a physicist at University of California, Berkeley, and lead author of a new paper discussing the findings, said in a statement.

For the study, published last week in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, researchers used satellite data from NASA's Ionospheric Connection Explorer, or ICON, and the European Space Agency. They found that a plume of gas and particles after the eruption spurred hurricane-speed winds and unusual electric currents in the upper reaches of Earth's atmosphere, also known as the ionosphere.

The data showed the volcano sent strong winds into the Earth's thinnest atmospheric layers, researchers said, where they picked up speed. "Upon reaching the ionosphere and the edge of space, ICON clocked the windspeeds at up to 450 mph — making them the strongest winds below 120 miles altitude measured by the mission since its launch," the agency said in a statement. (The strongest hurricanes on Earth reach a maximum windspeed of around 200 miles per hour.)

Once in the upper atmosphere, the strong winds also affected a thin, electric, east-to-west flowing current called the equatorial electrojet. After the eruption, the current surged to five times its usual strength and changed directions several times.

"The equatorial electrojet is a very strong electrical current of hundreds of kilowatts that exists in a narrow band near the equator," Harding told Space.com. "It typically flows eastwards and sometimes can be reversed by geomagnetic storms. But this was the first time we have seen it completely reverse and strengthen because of something that happened on the ground."

The findings add to scientists' knowledge of how events on Earth can affect weather in space, which is poorly understood. In order to gather more data and tease out that relationship, NASA plans to send a fleet of small satellites to Earth's upper atmosphere as part of its upcoming Geospace Dynamics Constellation.

Dit artikel is oorspronkelijk verschenen op z24.nl