- Russia's navy has taken high-profile losses against a outnumbered and outgunned Ukrainian adversary.

- The losses themselves are not catastrophic for Russia's navy but they are blows to Russian prestige.

- They also come a little over a century after another Russian naval debacle on the other side of the world.

Since Russia launched its attack on Ukraine in late February, the Russian navy has suffered high-profile losses against a heavily outnumbered and outgunned adversary.

The Russians have lost at least five Raptor-class patrol boats, one Tapir-class landing ship, one Serna-class landing craft, and most notably the Moskva, a Slava-class guided-missile cruiser that was also the flagship of the Black Sea Fleet.

The losses themselves are not catastrophic for the Russian navy and are unlikely to alter the course of the war or the balance of power in the Black Sea, but they are blows to Russian prestige and come a little over a century after another historic debacle for Russia: the Battle of Tsushima, the last time a Russian navy flagship was sunk in combat.

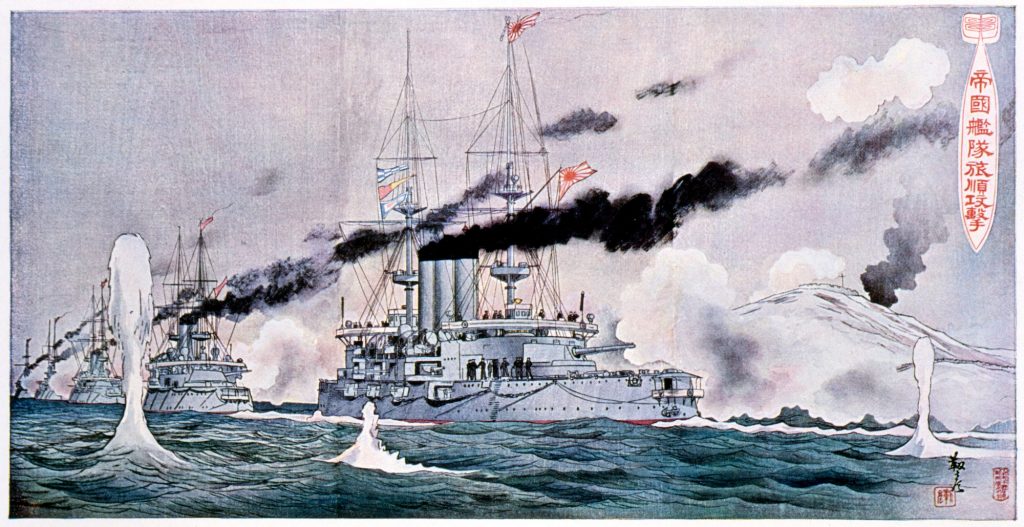

Fought in the waters between Korea and southern Japan by ships of the Japanese and Russian empires on May 27 and 28 in 1905, the battle cemented Japan's rise as an equal to Western powers and had a lasting impact on both Japan and Russia.

Competing empires

Tensions between the Japanese and Russian empires had been building since Japan's overwhelming victory in the Sino-Japanese War in 1895.

Japan, equipped with an organized, modern army, was pursuing ambitions in Korea and China that brought it dangerously close to Russian interests, especially in Manchuria and Korea.

Of particular importance to the Russians was Port Arthur, now Dalian, a Chinese port that was leased to Russia and was its only warm-water Pacific port. Port Arthur became the headquarters of Russia's Pacific Fleet and there were plans to connect it to Russia via the Trans-Siberian Railway.

Negotiations between Japan and Russia over the future of the region went nowhere, and so, on February 8, 1904, the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the main part of the Russian Pacific Fleet at Port Arthur, formally declaring war hours later.

Japan gained a naval advantage relatively quickly. It fought off an attempt by the main part of the Russian Pacific Fleet to break the blockade of Port Arthur and largely defeated Russia's Vladivostok-based squadrons at Chemulpo Bay and Ulsan — victories that allowed Japan to effectively dominate the Pacific.

Unwilling to concede defeat, and with Japanese ground forces beginning a siege of Port Arthur itself, Russia's Tsar Nicholas II ordered the creation of the 2nd Pacific Squadron, which was to be made up of ships from the Baltic Fleet.

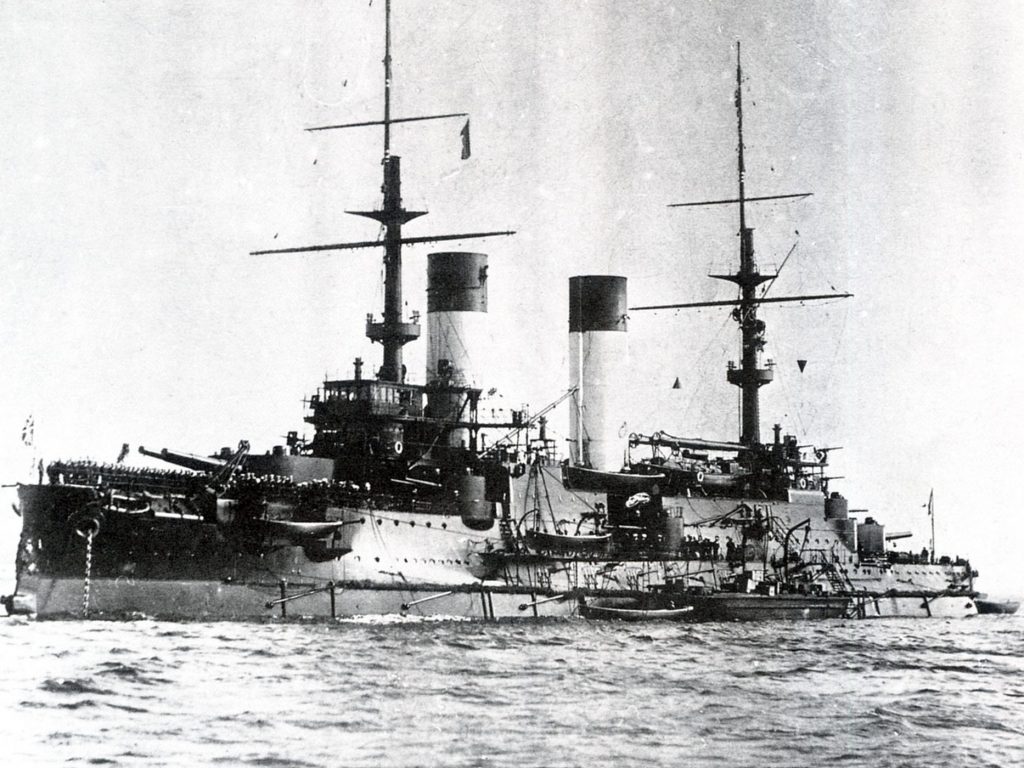

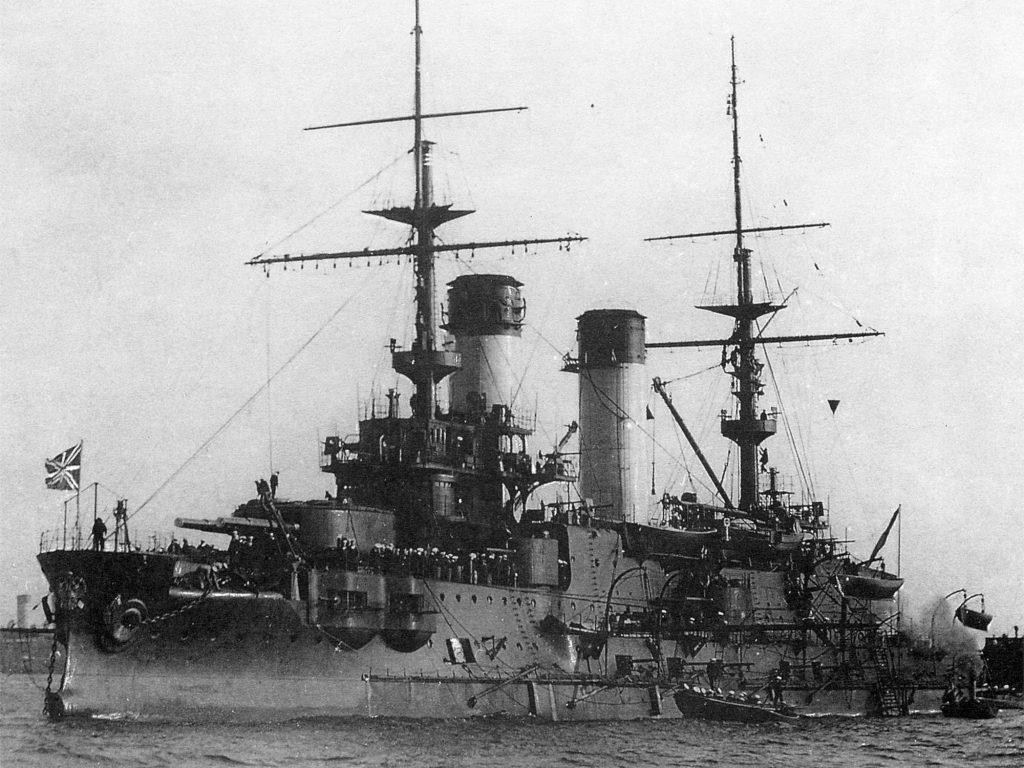

Commanded by Vice Adm. Zinovy Rozhestvensky, the 2nd Pacific Squadron was composed of some 40 ships, including 11 pre-dreadnought battleships, nine cruisers, and nine destroyers.

Sailing from the Baltic in October 1904, they were supposed to relieve the Pacific Fleet at Port Arthur, destroy any Japanese ships they encountered, and cut the supply lines between Japan and mainland Asia.

Russia's doomed fleet

Russia's navy had been modernized in during the latter half of the 1800s, but while the 2nd Pacific Squadron appeared strong on paper, it was not a first-rate naval force. Some of the warships were new and untested, but many were old and bordered on obsolete. Others were little more than auxiliary ships with guns mounted on them.

Russian Navy leadership was also of low quality. Many of its officers came from wealthy and connected families who simply bought their commissions. The rank-and-file sailors were not much more professional, as many of them were inexperienced conscripts.

These issues were on full display during the seven-month, 18,000-mile journey to the Pacific.

While in the North Sea near England, the fleet opened fire on British fishing trawlers, somehow thinking they were Japanese torpedo boats. Two fishermen were killed, one was injured, and one trawler was sunk with four more damaged. In the chaos, some of the Russian ships even fired on each other, causing casualties and damage.

Diplomatic maneuvering managed to prevent the British from joining the war on the side of Japan, but the Russian fleet's troubles were only beginning.

Most of the fleet sailed around Africa rather than through the Suez Canal. The longer journey took a toll on the crews, who had never experienced such a different climate or such a long time at sea. The ships themselves were also under considerable strain. During gunnery practice with a mock target towed by a cruiser, the only thing the fleet hit was the cruiser.

With no allies, the Russians couldn't dock in friendly ports, and so they had to take on more coal while at sea. Conditions on the ships deteriorated, and a number of sailors died of disease and respiratory issues.

By the time the fleet was in Madagascar in January, Port Arthur had fallen. Their mission was then changed: They were to meet the remnants of Russia's Pacific Fleet in Vladivostok before engaging the Japanese in a decisive battle.

Slaughter at Tsushima

When the Russian ships finally reached the Tsushima Strait on the night of May 26, 1905, Rozhestvensky attempted to slip through unnoticed. Unfortunately for him, one of his ships had been spotted by a patrolling Japanese vessel.

Even more unfortunate, the Russian ship mistakenly believed the Japanese vessel was a lost Russian ship and signaled that more Russian ships were nearby.

With the location of his enemy confirmed, Japanese Adm. Tōgō Heihachirō's Combined Fleet, which included four modern battleships, over 20 cruisers, 21 destroyers, and 43 torpedo boats, set out to meet them.

On the morning of May 27, the fleets made contact. Before the firing began, Tōgō hoisted a signal flag that conveyed a predetermined message to his fleet: "the Empire's fate depends on the result of this battle, let every man do his utmost duty."

The ensuing battle was a slaughter. In addition to better training, discipline, and experience, the Japanese were equipped with modern armor-piercing rounds that tore the Russian ships apart.

By the end of the day, four Russian battleships were sunk. Imperator Aleksandr III sank with its entire crew of over 700, while Borodino sank with all but one of its more than 800 crew members.

The flagship, Knyaz Suvorov, sank with all but 20 officers, while about half of Oslyabya's crew went down with the ship. A number of cruisers and destroyers were sunk as well.

As night fell, the survivors attempted to make it to Vladivostok under cover of darkness. Tōgō's destroyers hunted them down, picking off two more battleships and several other warships. By the following afternoon, most of the survivors surrendered.

Lost prestige

Russian losses were immense, 21 ships sunk or scuttled and seven captured. Only three ships reached Vladivostok, though six others made it to neutral ports in China, the Philippines, and Madagascar.

Over 4,000 Russian sailors were killed and almost 6,000 were captured. The Japanese lost only three torpedo boats with just 117 killed and about 500 wounded — including a young Isoroku Yamamoto, mastermind of the attack on Pearl Harbor, who lost two fingers in the battle.

The Russian navy's prestige never recovered from Tsushima. Unable to be rebuilt to the same grand scale, it saw little major action in World War I. The Soviet Navy also only saw limited action in World War II and never truly proved itself during the Cold War, though Soviet submarines were a constant concern for NATO navies.

Today, the Russian navy boasts a smaller, more modern fleet that is focused on green-water operations rather than high-seas campaigns, but its surprising losses against Ukraine show it has yet to regain the dominance lost a century ago.