- Access to public space has been restricted in the pandemic, from libraries to parks to transit to sidewalks.

- While it’s still too early to predict exactly how public space will evolve, some concerning patterns have emerged.

- Who gets to exist in these spaces and how will likely be drawn along race- and class-based lines, experts told Insider.

- “Who knows if we’ll ever be able to do the things we used to do?” one library director said. “I hope we can.”

- Visit Insider’s homepage for more stories.

On a Friday in early March, Jennifer Pearson looked around her library in Lewisburg, Tennessee.

“The library was full of older people,” Pearson, the library’s director, said. “I thought, if I don’t close this space, they will never stop coming to it, so I have to close it, for their good and for my staff.”

The Marshall County Memorial Library closed in mid-March due to the pandemic — and with its closure came the shuttering of one of the county’s only public spaces.

“In my rural area, and in lots of rural areas, this is the only thing they have,” said Pearson. “There aren’t other public spaces where you can go and just sit and be all day without having to buy anything or get in trouble for loitering.”

The library began a cautious, phased reopening in May, with curbside pickup of reserved items. The space began reopening by advance booking later that month. Books are now quarantined for 72 hours upon return. Computer time is bookable, and WiFi hotspots are being checked out, crucial in a county where not everyone has broadband or computer access.

Craig F. Walker/The Boston Globe/Getty

In June, the library began offering book slots in advance to browse the books. But one of the library's main functions, as a social gathering place, remains a distant hope.

"For at least 15 to 20 years, libraries have been evolving into community hubs, places to come and stay and have meetings and meet your friends and come on in and stay awhile," said Pearson, who is also president of the Association for Small and Rural Libraries. "We can't be that right now."

The ways in which people use public space have shifted dramatically during the pandemic

Some of these changes are long-time fantasies of urbanists and planners, ideas that would never have been tried without the precipitating factor of a major social disruption.

In New York, parking spaces are handed over to outdoor dining, and some blocks have closed altogether. Bike lanes have popped up all around the country. Streets have been shut to cars, and some cities are going to make the closures permanent, like Seattle, which has made 20 miles of streets pedestrian and cyclist only.

Overall, the consciousness about the importance of public space has risen.

"Under the pandemic, people care much more and are appreciating much more the parts of open space that we have," Jeff Hou, the director of the Urban Commons Lab at the University of Washington, told Insider. "They realize how important these amenities are for our physical and mental well-being. There's a new awareness and consciousness about parks and open space that we sometimes take for granted."

Alexi Rosenfeld/Getty

But not all kinds of public spaces are able to be appreciated in the same ways. Enclosed public spaces like libraries and trains face significant challenges due to socially distancing regulations, and ongoing, warranted fears about indoor spread of the virus.

And race and class-based disparities in access to and amenability of public space in the US have manifested in a variety of ways: when law enforcement disproportionately enforces social distancing regulations on people of color; in transit systems upon which non-white and lower income people rely; and in the shuttering of libraries and public restrooms, used heavily by homeless populations in cities and towns across the country.

Much remains to be seen about how the pandemic will reshape public space in America, and researchers say it's far too early to draw conclusions. But it's clear that the future of public space post-pandemic will be intricately linked to the disparities and inequities along race and class-based lines that have been endemic both to the pandemic and, historically, to the spaces themselves.

"We need to push more on questions of these changes, who benefits from them?" said Jordi Honey-Rosés, an associate professor in the School of Community and Regional Planning at the University of British Columbia, who recently co-authored a paper on emerging questions about public space and COVID-19. "Who are the winners and losers of the changes we're likely to see? And who might be more vulnerable or likely to be excluded from them?"

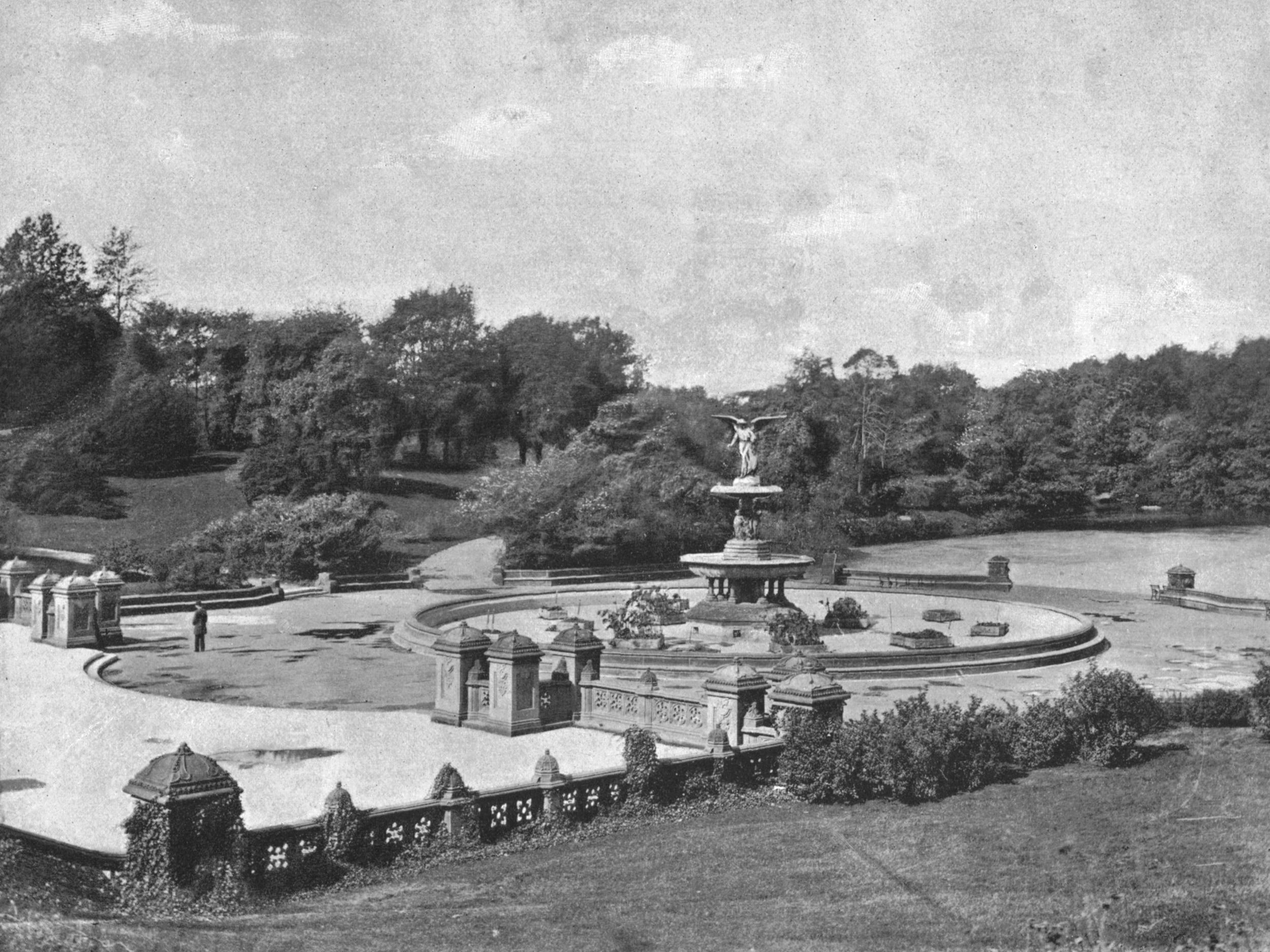

Pandemics and concerns about health have a long history of shaping cities, particularly outdoor spaces like parks

City parks as we know them largely came to be because of illness in nineteenth-century British cities.

The Print Collector/Getty

"There was a belief that they generated oxygen, that they could be the 'lungs of the city,' and that if you built them, it would decrease disease," said John Crompton, a professor at Texas A&M. Crompton has studied how cities like London and Liverpool built parks based on misguided ideas about germ theory, and how those ideas spread to the US a few decades later.

"If you think about, why would the city of New York in the 1850s invest what was the equivalent of half a billion dollars in today's money in building a park?" Crompton said.

The answer stemmed from concerns about disease and the health of the city, which science at the time believed could be solved with parks. The idea of "public health" — that the health of the city's poorest residents was tied to that of its wealthiest residents — was growing increasingly popular. Cities including Boston and Philadelphia also built public parks in the late nineteenth century.

Though the specifics of that era's germ theory turned out to be incorrect, there is now a significant body of literature tying access to green spaces with mental and physical well-being. But just as it does now, the construction of these parks was shaped by racist and classist concerns.

"Who do you think came to live near the parks? The rich," Crompton said. And the construction of Central Park in 1857 led to the displacement of people who lived in Seneca Village, a predominantly Black community of property-owners who lived on the western perimeter of what is now the park.

More than a century later, displacements are still happening around outdoor space

Isabelle Anguelovski, who directs the Barcelona Laboratory for Urban Environmental Justice and Sustainability, said that this will be important to keep in mind in the creation of any new green spaces that emerge post-pandemic.

"It's not just a question of increasing access on the map in neighborhoods that didn't have these green spaces before," Anguelovski said. "It's about thinking, okay, what's happening with real estate prices?"

Justin Sullivan/Getty

In the context of COVID-19, the question is also how these spaces are currently being maintained and policed. Lorien Nesbitt, professor of urban forestry at the University of British Columbia, said that the elimination or suspension of ordinance laws that prohibit drinking in parks, for instance, can help create a less criminalized and more broadly welcoming space.

But the street economy has also suffered enormously. New School urban researcher Miodrag Mitrosinovic observed that an entire economy built around buying and selling in urban public space is collapsing and has almost no safety net.

"There are hundreds of thousands of people who depend on the regular access to public space to sell stuff, sometimes illegally and very often legally with permits, and the closure of that includes the loss of entire livelihoods," he said.

In some ways, the use of outdoor public space has taken a particularly powerful form during the pandemic: protest

When Jordi Honey-Rosés and his colleagues were writing their paper on emerging questions in April, he said, "The concern was, what will be the future of public space as a tool for political expression and dissent? Will people avoid large public gatherings for these purposes?" But, he said, "I think the George Floyd protests have shown that the answer is no."

Still, the protests were in part about public space and how it's policed: who gets to move through it freely and who doesn't, and the long history of Black men killed by police simply for moving through space.

"In societies that do not have vibrant and dynamic public space, there is rarely a vibrant public sphere," Mitrosinovic said. "Public space often manifests the political climate." The political climate, with its divisions along lines of race and class, is manifesting clearly in American public space, and the present and future both look bleak.

Associated Press/Evan Vucci

Libraries are spaces that have historically addressed some of these disparities and have served communities that have fewer spaces. This has been true throughout the pandemic, even as their old mandates have become more difficult: in Washington State, Spokane Public Library opened a temporary homeless shelter.

In St. Louis and Columbus, libraries stepped in to provide free lunches to students when schools closed. Many worked to address PPE shortages and deliver hand sanitizer and masks. Some kept their bathrooms open as public restroom access became more sparse.

But they are a long way from being able to fulfill their function as gathering spaces. Erick Villagomez, a researcher and designer who is also the editor-in-chief of Spacing Vancouver, developed a series called the "The Six Foot City," imagining how enclosed spaces would need to change to accommodate social distancing.

Most cities now, he says, are more like "the three to four-foot city," the typical amount of social space in which people operate. To transform any indoor space to accommodate social distancing creates a host of problems immediately. "It's an extremely difficult problem to solve, because libraries are built on lounging," Villagomez said. "A lot of the success of a library has to do with its role as a social space."

At the Marshall County Memorial Library, kids went back to school on August 3; the library is now open in the evenings and on Saturdays so kids can come in if they need WiFi, by appointment only.

Certain aspects of the social library have lived on: The avid crochet group that normally meets in the library transferred to Zoom when it closed down. In a way, now, the question is how to remain a public space when space itself is so limited.

"The folks that come in and just hang all day can't take advantage of that, and there's really nowhere for them to go, no space where you can go and stay all when you're hot or cold," Jennifer Pearson said. "It was bad in the summer when it was hot and it'll be worse in the winter when it's cold, and my hope is that we'll see some relief from the virus so we can open our space before the weather gets really bad."

"Who knows if we'll ever be able to do the things we used to do?" she said. "I hope we can."

Sophie Haigney is a freelance journalist who often writes about technology and art. She has written for The New York Times, New York Magazine, Slate, and others.

Read more:

The coronavirus is forcing Americans to reckon with death like never before

Grieving my father during the pandemic taught me to make peace with an unknowable future