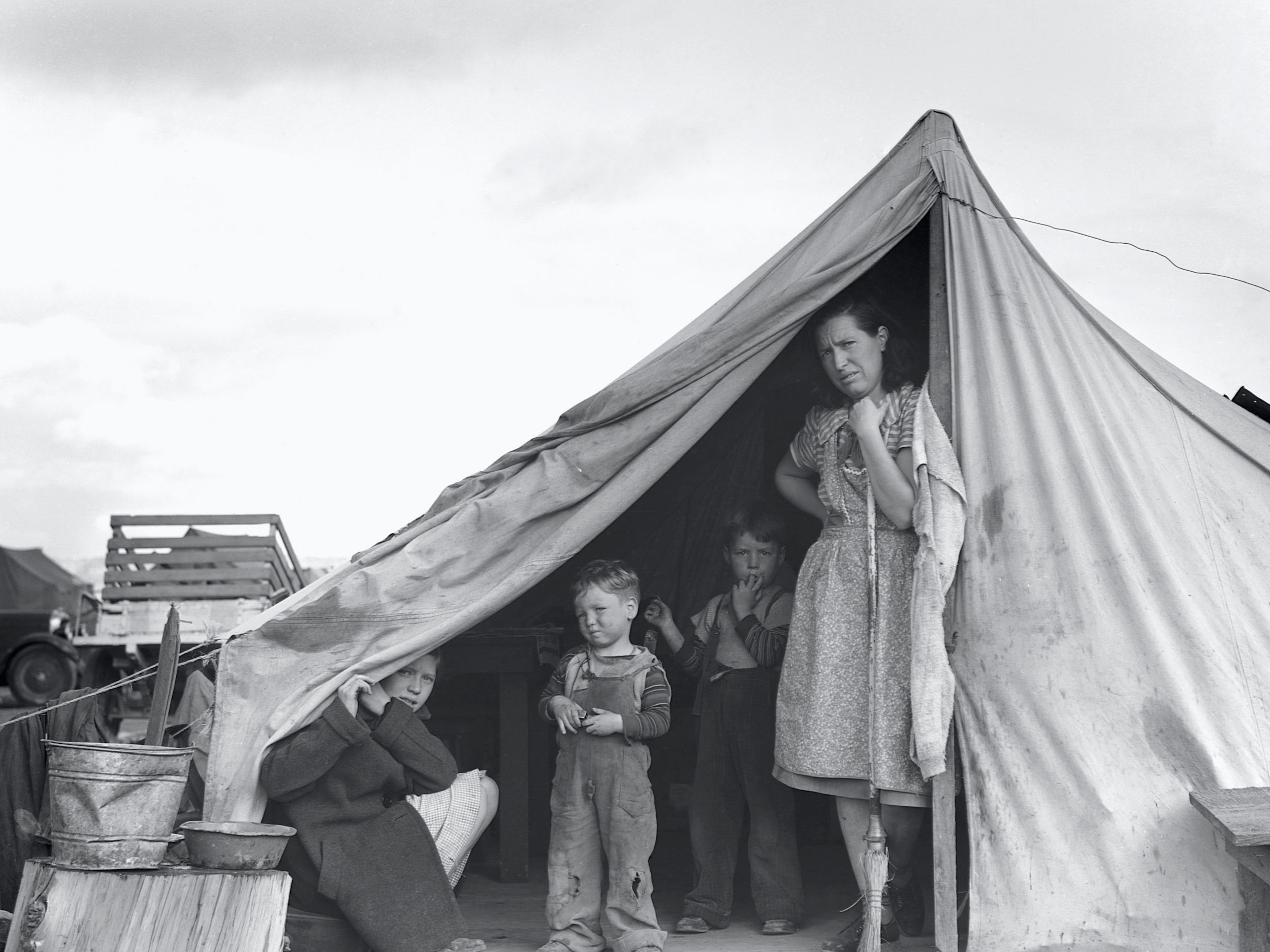

Visual Studies Workshop/Getty Images

- While the October 1929 stock market crash triggered the Great Depression, multiple factors turned it into a decade-long economic catastrophe.

- Overproduction, executive inaction, ill-timed tariffs, and an inexperienced Federal Reserve all contributed to the Great Depression.

- The Great Depression’s legacy includes social programs, regulatory agencies, and government efforts to influence the economy and money supply.

- Visit Insider’s Investing Reference library for more stories.

The Great Depression was the worst economic period in US history.

It lasted roughly a decade: from 1929, the year the stock market crashed, to 1939, when the US started mobilizing for World War II. Industrial production fell by nearly 47% and gross domestic production (GDP) declined by 30%. Almost half of US banks collapsed, stock shares traded at a third of their previous value, and nearly one-quarter of the population was jobless — at a time when unemployment insurance didn’t exist.

While the stock market crash of 1929 marked the start of the crisis, it wasn’t — contrary to popular belief — the sole reason for it. Many other factors combined to create the Great Depression, from ill-timed tariffs to misguided moves by the young Federal Reserve. “The crash was not a cause, but a triggering event,” says David Mitnick, a professor of business administration and of public and international affairs at the University of Pittsburgh’s Katz Graduate School of Business.

This begs the question: What exactly caused the Great Depression? And could such a severe downturn happen again?

1. The speculative boom of the 1920s

As anyone who’s read “The Great Gatsby” or seen “Chicago” knows, the period popularly called the “Roaring Twenties” preceded the crash. GDP grew at an annual rate of 4.7%, while the jobless rate averaged 3.7%. From 1920 to 1929, total wealth in the U.S. more than doubled, and individual Americans started investing in the market in a big way.

But all was not as roaring as it seemed. Consumer debt increased, and companies over-extended themselves too. Financial institutions became heavily involved in stock market speculation. In some cases, they created securities "subsidiaries" with their own brokers secretly selling their own stocks — what would be a clear conflict of interest today.

Weak regulations had opened the way for a period of wild speculation on stock exchanges. Being "in the market" was the "in" thing, but many investors weren't researching companies and buying based on the fundamentals — they were just gambling that the stock would keep going up.

Even worse, many people bought shares on margin, generally needing just 10% of a stock's price to make a purchase (not realizing they'd be on the hook for the whole amount if the price fell). That, in, turn, inflated prices, with shares selling for more money than justified by their companies' actual earnings.

Still, the stock market stubbornly kept on climbing. That is, until October 1929, when it all came tumbling down.

2. Stock market crash of 1929

Catching on to the market's overheated situation, seasoned investors began "taking profits" in the autumn of 1929. Share prices started to stutter.

They first crashed on Oct. 24, 1929, when the markets opened 11% lower than the previous day. After this "Black Thursday," they rallied briefly. But prices fell again the following Monday. Many investors couldn't make their margin calls. Wholesale panic set in, leading to more selling. On "Black Tuesday," Oct. 29, investors unloaded millions of shares — and kept on unloading. There were literally no buyers.

"The system fell back on itself like a house of cards," says Mitnick.

From 1929 to July 1932, the market lost more than 85% of its value. The Dow Jones Industrial Average sank from a 1929 high of 381.17 to as low as 41.22 in 1932.

And it caused other simmering economic problems to come to a boil.

3. Oversupply and overproduction problems

Mass production powered the 1920s consumption boom. But it also led to overproduction on the part of many businesses. Even before the crash, they started having to sell goods at a loss.

A similar crisis was occurring in agriculture. During World War I, farmers had bought more machinery to boost production — a costly move that put them in debt. But, in the post-war economy, they ended up producing far more supply than consumers needed. Land and crop values plummeted.

It all resulted in a drop in prices, both agricultural and industrial, which decimated profits and hurt already over-extended enterprises.

4. Low demand, high unemployment

Losing money forced companies to cut production — and their workforce. Debt-ridden consumers then stopped spending. That only worsened the situation, causing more businesses to collapse or cut back and, of course, lay off more people. During its peak in 1933, the jobless rate reached 24.9% — 15 million Americans out of a population of 125.6 million — and it was still nearly 19% in 1939.

Bettmann/Getty Images

5. Missteps by the Federal Reserve

Throughout the '20s, banks had been irresponsible, letting their reserves get dangerously low. But the Federal Reserve was even more so, many economists and historians now think. "The Great Depression can be laid at the foot of the Fed," says Aleksandar Tomic, program director of Master of Science in applied economics at Boston College.

By keeping interest rates low in the early to mid-1920s, the Fed contributed to the heady expansion. Then, after the crash, it did just the opposite of what economists would advise today: Instead of lowering interest rates, the Fed raised them, doubling them in 1931 from their pre-Crash levels. The idea was to discourage lending and borrowing — the "wild speculating" that encouraged the market to bubble, then burst.

The Fed also followed the "liquidationist" policy of then-Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon, which essentially let banks collapse. The thinking: Weed out the financially irresponsible institutions, and overall, a stronger, sounder banking system would emerge. But instead of the bad apples, it was largely smaller banks that ended up going under. By 1933, 11,000 of them had failed, wiping out the savings of millions.

Ultimately, the decrease in the money supply led to deflation. That, in turn, caused sky-high increases in real interest rates, which choked off any chances of companies investing or expanding.

6. A constrained presidential response

President Herbert Hoover's response to the economic crisis was tardy. A believer in minimal government intervention, he considered direct public relief character-weakening. He did eventually start spending and launched lending and public works projects. Still, according to many economists, it was too little, too late.

Historical/Getty Images

7. An ill-timed tariff

As demand declined, big business and agriculture, feeling the effect of cheap goods from abroad, lobbied for protection. Congress obliged with the United States Tariff Act of 1930, aka the Smoot-Hawley bill, which raised tariffs on foreign products by about 20%.

Multiple countries retaliated with their own tariffs on US goods. The inevitable result was a trade melt-down. In the next two years, US imports fell 40%.

No markets abroad. No demand at home. Small wonder that economic activity ground to a standstill.

Effects of the Great Depression

When Franklin D. Roosevelt became President in 1933, he almost immediately started pushing through Congress a series of programs and projects called the New Deal. How much the New Deal actually alleviated the depression is a matter of some debate — throughout the decade, production remained low and unemployment high.

Bettmann/Getty Images

But the New Deal did more than attempt to stabilize the economy, provide relief to jobless Americans and create previously unheard of safety net programs, as well as regulate the private sector. It also reshaped the role of government, with programs that are now part of the fabric of American society.

Among the New Deal's accomplishments:

- Worker protections, like the National Labor Relations Act, which legitimized unions, collective bargaining, and other employee rights

- Public works programs, aimed at providing employment via construction projects — a win-win for society and individuals

- Individual safety nets, such as the Social Security Act of 1935, which created the pension system still with us today, and unemployment insurance

A legacy of government regulation

New Deal legislation also ushered in a new era of government regulations — and the underlying concept that even a free-enterprise system can use some federal oversight. Milestone measures include:

- The Glass-Steagall Act of 1933, which separated investment banking from commercial banking to prevent conflicts of interest and the sort of speculation that led to the 1929 crash (it was repealed in 1999, though some of its regs remain in the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010)

- The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation to oversee banks and protect consumer accounts, via FDIC deposit insurance

- The establishment of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to oversee the stock market, create securities legislation, and protect investors from fraudulent practices

"The biggest legacy is a change in the view of government's responsibilities — that it should take an active part in addressing economic and social problems," says Tomic.

Graphic Artis/Getty Images

Could the Great Depression happen again?

"The highest unemployment rate since the Great Depression" screamed headlines in April 2020, when the jobless level hit 14.7% of the US population. (It declined overall since, though troublingly, it remains in the double-digits among Blacks and Hispanics).

There are other grim statistics in the coronavirus era: From Feb. 12 to March 30, 2020, the DJIA declined 35%. And in the second quarter of 2020, GDP fell at a 32.9% annualized rate, the steepest drop since 1947.

"Among certain groups, there is absolutely a depression now," says Tomic.

But could there be another Great Depression?

Though there's by no means a consensus, many economists argue that another such catastrophe, at least one caused by internal factors, is unlikely. That's largely because the contemporary federal government can draw on many more policy and monetary tools, ranging from unemployment compensation to easing of the money supply.

As, indeed, it has done. Take the Great Recession of 2007-2009. It too was kicked into high gear by a financial-market crisis, the subprime loan meltdown. But the Fed quickly slashed interest rates. And thanks in large part to a massive government bailout of the banking, insurance, and automobile industries, and an $800 billion-plus stimulus package, the downturn officially lasted less than two years. Though sluggish, the economy recovered — and eventually sparked a record-breaking bull market.

Memories of the Great Depression may never fade. But nowadays, says Brad Cornell, managing director of Berkeley Research Group, "we know enough and can respond quickly enough so that these sorts of endogenous downward spirals are not going to happen again."