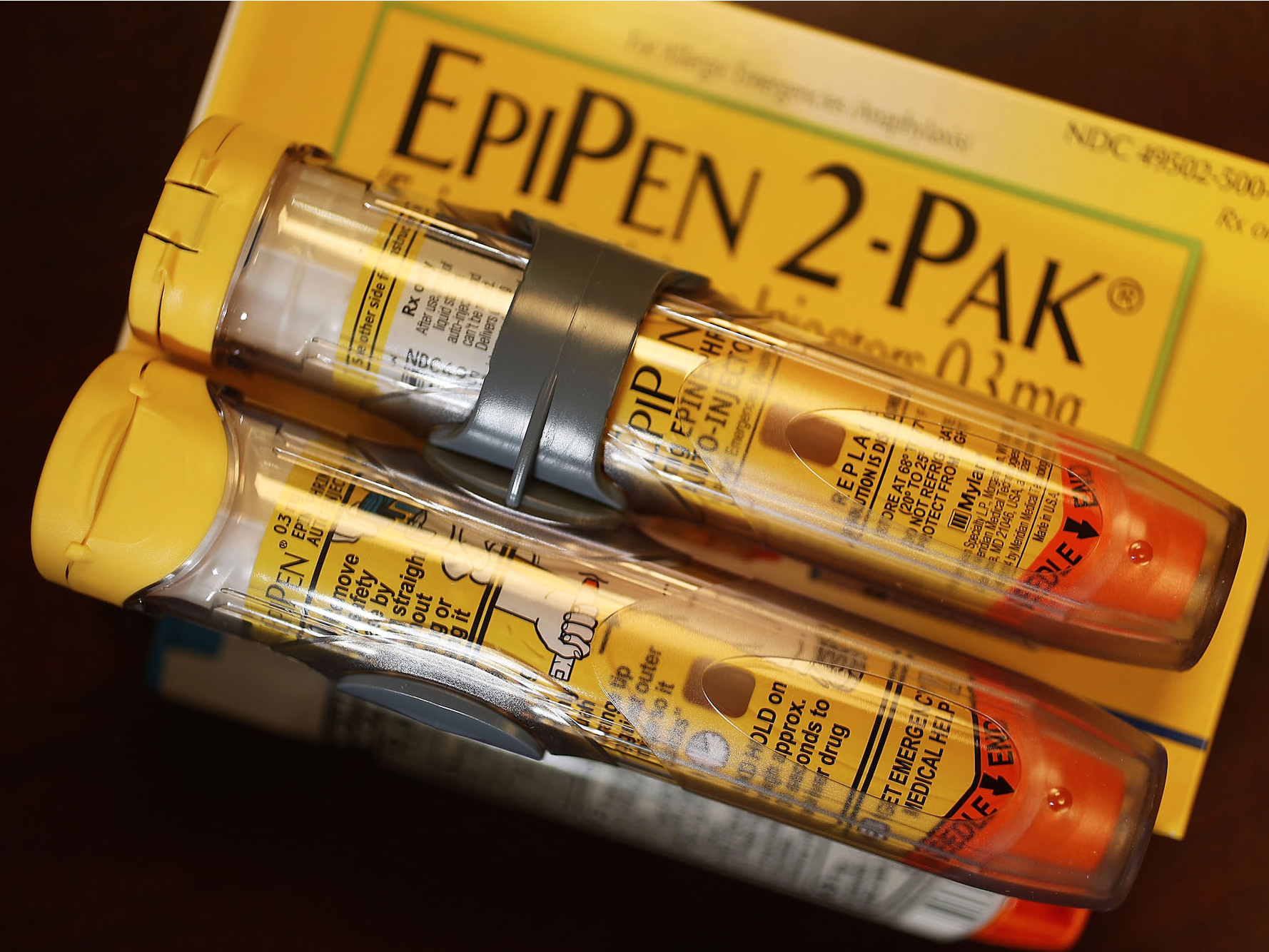

In 2016, the EpiPen became a symbol of the drug-pricing problem in the US.

Over a decade, the price for a two-pack has gone up from $93.88 to $608.61, an increase of more than 500%. On Thursday, the FDA approved Teva’s generic version of the drug, dealing a blow to branded EpiPen-maker Mylan.

The injectable device delivers a dose of epinephrine, otherwise known as adrenaline, to treat extreme allergic reactions.

It’s been around for more than a century. And the pen that delivers the medication has been around since the 1970s, when it was first developed for the military.

Here’s the story of how a device that’s now a household name became one of the most controversial drugs in the US.

Epinephrine, another name for the hormone adrenaline, is something our bodies produce naturally. It increases blood flow to the muscles during "fight-or-flight responses."

Source: Mental Floss

Japanese chemist Jokichi Takamine is credited as one of the first people to discover and isolate adrenaline as its own chemical. Not long after its discovery, scientists figured out how to produce it in large enough quantities to see how it could be used in different medical settings.

Source: The Practice of Medicinal Chemistry

Doctors continued to investigate how adrenaline works during the early part of the 20th century. In the past 100 years, it's been extensively studied, with more than 12,000 studies referencing it.

Source: Pharmacological Reviews, PubChem

The study of epinephrine jump-started other areas of emergency medication for heart and lung problems. The hormone is now used in hospitals around the world and is included on the WHO's list of essential medicine. It only costs a few dollars for a vial.

Source: World Health Organization

In the 1970s, Sheldon Kaplan, a biomechanical engineer, unknowingly invented the ultimate way to self-inject epinephrine. At first, his device, called the ComboPen, was used by the military to protect soldiers in the event of chemical warfare. The military needed a device that wouldn't react with the drug inside, and that could be easy to use in emergency situations.

Source: The Tampa Bay Times, National Inventors Hall of Fame

Shortly after, Kaplan and others noticed that this same device could be used to deliver emergency epinephrine to treat allergic reactions. The drug and device combo we now know as an EpiPen was first approved by the FDA in 1987. By then, it was owned by a company called Meridian Medical Technologies.

Source: FDA

Meridian Medical is now a subsidiary of Pfizer, where it still makes a host of other auto-injector devices — including an anti-nerve-gas pen still in use by the military.

Source: Meridian Medical Technologies

The EpiPen passed hands a few times on the commercial side of things before ending up with Merck KGaA, a German company that sold its generics business to Mylan Pharmaceuticals in 2007. (Meridian — a Pfizer company — is still the contract manufacturer of the EpiPen, though it is sold and marketed by Mylan.)

Source: Reuters, Morning Consult

When Mylan acquired the EpiPen, the drug was making about $200 million a year. At its peak, it made more than $1.1 billion a year. In 2016, Mylan has about 90% of the market share for epinephrine devices, though that's decreased to 73.5%.

Source: Bloomberg, PR Newswire, Fortune

Other devices do exist, but none has been able to grab much of the market from the EpiPen. Among them was a device called Twinject that was first approved in 2003 and then was later updated to become Adrenaclick. Another device, the Auvi-Q, was first approved in 2012.

The FDA recalled Auvi-Q in 2015, and was pulled off the market for a few years. It returned in February 2017, but with a much higher list price higher than the Epipen: $4,500 for a two-pack. In June 2017, another alternative entered the market called Symjepi, consisting of pre-filled syringes of epinephrine.

Source: Business Insider, Business Insider

In an interview with Fortune magazine in 2015, Mylan CEO Heather Bresch called the EpiPen her "baby." As the price began to rise, so did Mylan's education efforts and marketing strategies.

Source: Fortune

Among those steps to making the EpiPen a billion-dollar drug, President Barack Obama signed legislation in 2013 that helped public schools build up emergency supplies of EpiPens.

Source: White House

"There was very, very little awareness," Bresch said in a 2016 interview with CNBC. "We took on — we have doubled the lives of patients that are carrying an EpiPen. We have passed legislation in 48 states to allow undesignated EpiPens to be in schools."

In response to the outrage over the high price tag, Mylan announced a change in the company's co-pay coupon system, more than doubling the available discount for a two-pack to $300. It also introduced an authorized generic version that costs $300. It currently holds about 50% of the epinephrine market.

Source: Business Insider, Business Insider

Following the public outcry over the price of EpiPens in August 2016, Bresch was brought in to testify before a Congressional committee.

Source: Business Insider

There were EpiPens used as props, frequent shouting matches, but otherwise not much came out of the hearing.

In October 2016, Mylan agreed to a $465 million settlement with the government after allegedly overcharging for its medicine.

Source: Business Insider

After a while, the outrage over drug pricing moved on to other prescription drugs, but it wasn't the end for the EpiPen saga. In March 2017, Mylan recalled some of its EpiPens in the US.

Source: Business Insider

In May 2017, the FDA said that there was a shortage of EpiPens in the US. The issues stemmed from delays at Pfizer's Meridian Medical Technologies, which makes the device. Mylan said on an earnings call in August that the device may not always be available, varying by pharmacy.

Source: MarketWatch

On Thursday, the FDA approved Teva Pharmaceuticals' generic version of the EpiPen after it had initially been shot down in 2016. "Today's approval of the first generic version of the most-widely prescribed epinephrine auto-injector in the U.S. is part of our longstanding commitment to advance access to lower cost, safe and effective generic alternatives once patents and other exclusivities no longer prevent approval," FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb said.

Source: Business Insider

The approval of Teva's generic comes at a pivotal time. Between Mylan's shortages and the beginning of the school year — a time when parents typically stock up on the emergency device — Teva could get ahold of a big chunk of the epinephrine market. Teva has not yet said when it will launch the drug and at what price.