- The Great Pacific Ocean Patch refers to a big swirling soup of plastic in the ocean.

- A new study found the patch was full of sea life that was living on the plastic debris.

- The findings challenged the assumption that coastal species couldn't survive in the open ocean.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is more than just a swirling vortex of plastic floating in the open ocean over 1,000 miles from land — it's also become an ecosystem hosting a variety of sea creatures that cling to the debris.

Scientists studying the infamous trash heap have found dozens of marine species that call the patch home, according to a study published Monday in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

They found 46 different species of invertebrates living on the debris, with the vast majority being species that are typically only found along coastlines, rather than the middle of the open ocean. The creatures included sponges, oysters, anemones, crustaceans, barnacles, and worms.

—Matthias Egger (@oceanegger) April 17, 2023

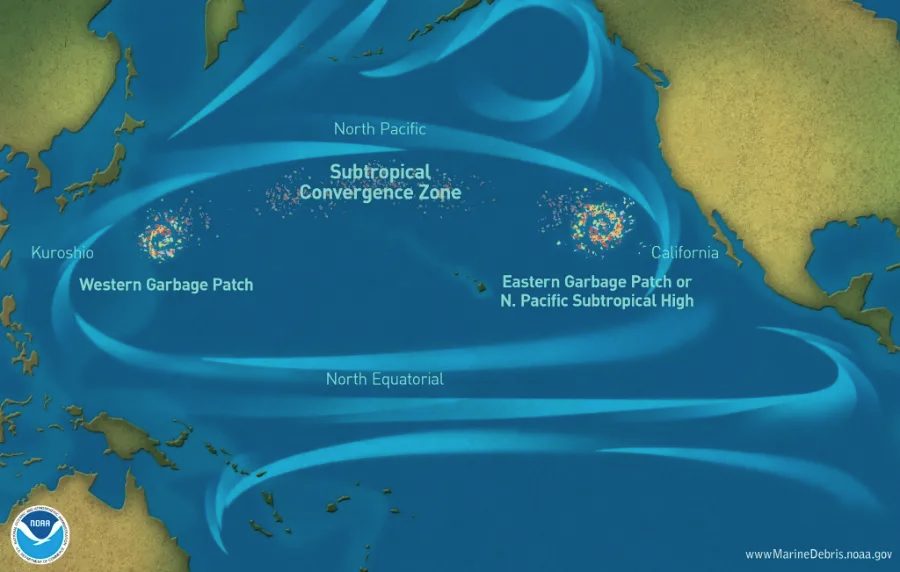

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch typically refers to an area of the Pacific Ocean between California and Hawaii in which floating trash concentrates due to factors like wind and currents. The area — which is more like a giant trash soup rather than one large continuous heap — has become an unfortunate example of plastic pollution in Earth's oceans.

The researchers collected 105 pieces of floating garbage from the patch and examined them for signs of life, ultimately identifying 484 invertebrates organisms. More than 70% of the trash collected was carrying coastal species.

"We expected to find some; we just didn't expect to find them at such frequency and diversity," study co-author Linsey Haram, then a postdoctoral research fellow at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, told The Atlantic.

The findings also contradicted the assumption that coastal species could not survive in areas of open ocean.

The authors said the results suggest the lack of available surface "limited the colonization of the open ocean by coastal species, rather than physiological or ecological constraints as previously assumed."

"They're having a blast," study coauthor Matthias Egger, head of environmental and social affairs at The Ocean Cleanup, told The Wall Street Journal of the coastal species living on the trash. "That's really a shift in the scientific understanding."

The study also noted that many of the coastal animals were living alongside animals that are at home in the open ocean on the same piece of debris, putting together species that historically were unlikely to come into contact.

Biogeographer Ceridwen Fraser at the University of Otago, who was not involved in the study, told The Atlantic: "As humans, we are creating new types of ecosystems that have potentially never been seen before."