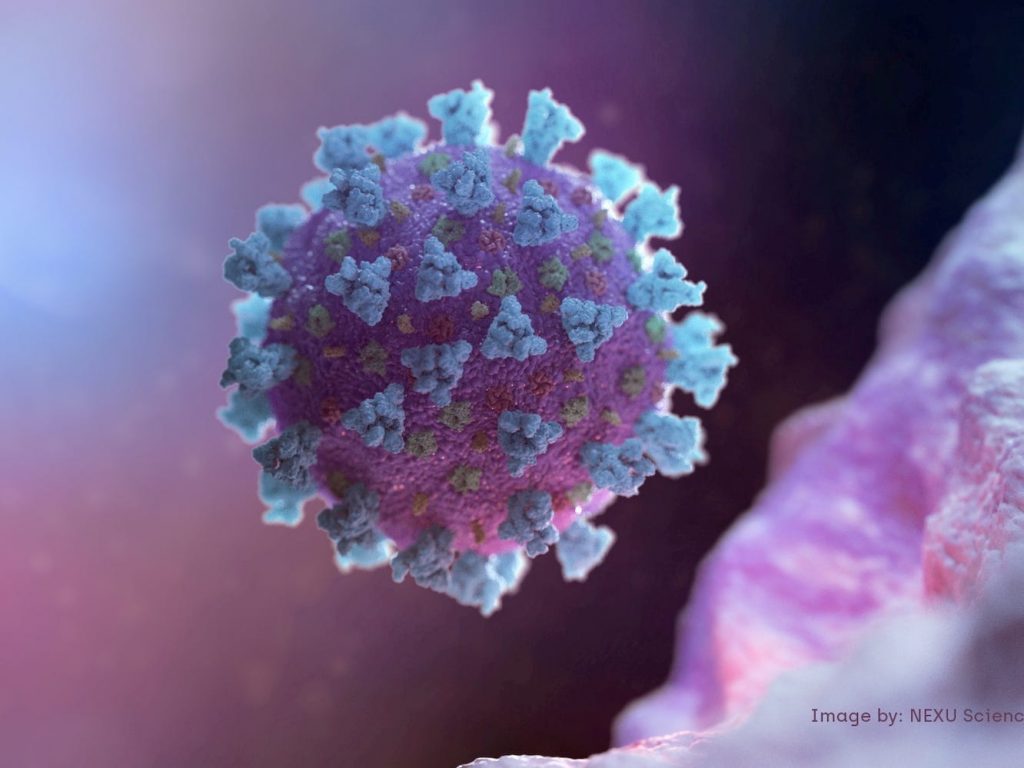

NEXU Science Communication/via REUTERS, File

- AY.4.2, a daughter of the Delta variant, has been detected in New York and California.

- Some evidence suggests AY.4.2 may be slightly more transmissible than Delta, but experts aren't sure yet.

- Studying Delta's mutations could be a step toward variant-specific treatments.

A new version of the coronavirus – AY.4.2, sometimes known as "Delta Plus" – grabbed scientists' attention when it began to spread in the United Kingdom in July. Now, the variant has been detected in New York and California, state health officials confirmed to Insider.

As of Friday, New York had confirmed five cases of AY.4.2, and California had detected two, in San Diego and San Francisco Counties.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention classifies the original Delta variant as a "variant of concern." Delta causes more infections and spreads faster than earlier forms of the virus, according to the CDC, and some data suggests that it might cause more severe infection in unvaccinated people, though that's not yet confirmed. As of October, Delta made up more than 99% of sequenced cases in the US.

AY.4.2 is a descendent of Delta, but the CDC does not classify sublineages separately.

In England, AY.4.2 accounted for 10% of sequenced samples as of Monday. It has been "steadily increasing in England," Jeffrey Barrett, director of the COVID-19 Genomics Initiative at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, wrote on Twitter last week. That pattern is different from other sublineages of the Delta variant, none of which had a "consistent advantage" over other Delta types, he added.

Still, AY.4.2 is replacing Delta in the UK at a much slower rate than Delta replaced the Alpha variant, which was previously dominant there, Barrett said.

Some evidence suggests that AY.4.2 might be slightly more transmissible than AY.4, the most common Delta variant in the UK, but experts say more research is needed to know for sure. Jeremy Kamil, a virologist at Louisiana State University Health Shreveport, told STAT News that to prove AY.4.2 is more transmissible, "you need to see the difference in more geographies," and also observe that trend "sustained over a long period."

Dr. Amesh Adalja, senior scholar at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, told Insider that the existence of a new variant isn't necessarily cause for concern.

"New variants are generated all the time," he said. "That's the normal thing that this virus is going to do. It's going to continue to mutate. While variants may garner headlines and people may write doomsday scenarios about them, most are not going to really change the trajectory of the pandemic."

Given that the original Delta variant became dominant around the world, it's unsurprising that we're now seeing Delta mutations and daughter lineages spring from it, Adalja added.

A COVID-19 moonshot: variant-specific vaccines and treatments

Karwai Tang/Getty Images

The US lags behind many nations in sequencing samples of the coronavirus. In the past six months, the US sequenced and shared results for just 6% of all positive tests, according to data from the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data. New York and California do more sequencing than most other parts of the US, Nevan Krogan, a molecular biologist at the University of California, San Francisco, told Insider.

Given all that, it's probable that AY.4.2 is present in multiple states and cases just haven't been spotted yet.

"If you look at where this virus is being reported as most prevalent, it's in England. Why? It's because they do better sequencing than anyone else in the world," Krogan said.

But sequencing the virus is just the first step - scientists then want to use that data to figure out what how the virus mutates and what those mutations mean.

"The jury's out in terms of what effects these mutations are actually having on the virus. And are they providing any extra power to the Delta variant?" Krogan said.

Answering that question will take significant time and research, but doing so would help scientists get ahead of the virus - to predict what combinations are coming down the line, rather than reacting to variants after they pop up.

"The hope is that there's a limited amount of mutations that can happen with this virus," Krogan said.

In the best-case scenario, he added, scientists could understand different variants well enough to develop variant-specific treatments or vaccines.

"That's precision medicine," he said.

In the meantime, there's a different way to slow the virus' rate of mutation: "The solution to the variants is the vaccine," Adalja said, adding, "if people want to be less scared of the variants, the solution is to have people vaccinated so there are less variants generally."

Dr. Catherine Schuster-Bruce contributing reporting.