Reuters

- When Mexico's most powerful drug lord died an unbelievable death, a team of federal agents raced against the clock to identify his body.

- Conspiracy theories about his demise have lingered for years, even getting a wink in Netflix's Narcos: Mexico.

- Speaking publicly for the first time, DEA agents who helped confirm his death give the full story behind one of the strangest chapters in the annals of Mexico's drug war.

The departed smiled up at the ceiling, his lips pulled back to reveal a row of bright white teeth.

The skin on the man's hideously distended hands shone a sickening gray-green color of rot, and his long, puffy face was heavily bruised, with deep, dark circles ringing his eyes and nostrils. Mottled patches of discoloration spread up his high forehead and across his cheeks.

Under the harsh glare and buzz of fluorescent lights, the body of one of Mexico's most powerful men lay in state, nestled within the plush white confines of a metal casket. The body was clad in a dark suit and a blue-and-red polka dot tie, his deformed hands deliberately forced together at his waist to mimic a state of repose, a hideous parody of an open-casket funeral.

In the place of mourners, photojournalists pressed up to the edge of the casket, inches away from a man who just days before could have, with a wave of his hand, ordered unspeakable violence against anyone insane enough to have treated him with such disrespect.

Along one wall, a row of men, some in white lab coats, others in drab, police-issue suits, stood with grim discomfort written across their faces as shutters clicked.

This ghastly wake in a government building in Mexico City on July 8, 1997 was the first glimpse of a man whose name much of the country knew but few dared to utter. Amado Carrillo Fuentes, the Lord of the Skies, the boss of Ciudad Juárez, and arguably the most powerful criminal kingpin in the nation's history was dead and his rotting corpse was displayed for all to see.

Reuters

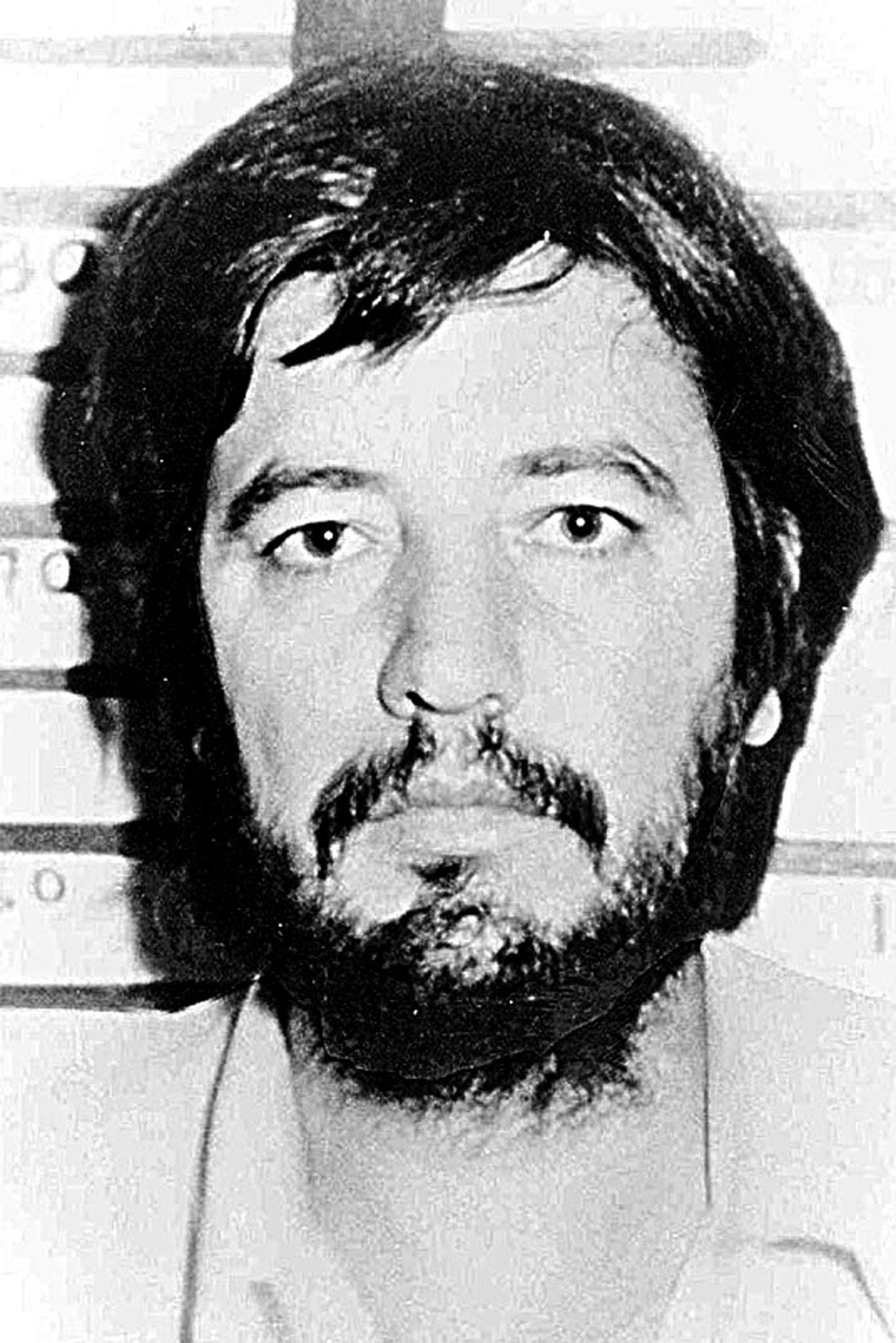

It was perhaps one of the most macabre press scrums in history, and a bitterly ironic fate for a man who had so carefully seen to it that so few photos of his likeness existed.

News of Amado's death had begun to filter out days before. According to the Mexican Attorney General's office - known by its Spanish acronym as the PGR - Amado had died on the operating table while undergoing plastic surgery, to alter his appearance, and liposuction.

Amado's family soon confirmed the story, lipo and all, telling reporters that he'd suffered a heart attack while under anesthesia.

But for many Mexicans, the story was almost too bizarre to believe. The PGR had invited reporters to see the body in hopes of dispelling any rumors or suspicion about Amado's fate.

It didn't work. The idea of Amado faking his death and vanishing into retirement flourished in Mexico's bustling rumor mills. One doubter, a barber cutting the hair of a Los Angeles Times reporter, insisted that the key to the coverup lay in the corpse's decaying limbs.

"Those aren't his hands," the barber said. "Those are the hands of a classical pianist."

"Some poor unfortunate person"

In the nearly quarter-century that has elapsed, a host of rumors and conspiracy theories have, unlike Amado, stubbornly refused to die - even in the archives of the wire service Agence Press Press, which listed a photo of Amado's "alleged" body.

In 2015, the idea found new life thanks to an article published on the English-language site of the Venezuelan state-sponsored news network Telesur. According to the report, which relied mostly on the extremely dubious word of a supposed cousin of Amado, Sergio Carrillo, the drug lord was doing just fine.

"He is alive," Carrillo said, according to Telesur. "He had surgery and also had surgery practiced on some poor unfortunate person to make everybody believe it was him, including the authorities."

This claim would be easily dismissed were it not for the larger constellation of conspiracies surrounding Amado's death. Instead, it's taken on a life of its own in a string of tabloid stories that have repeated Sergio Carrillo's claim.

(Attempts by Insider to verify Carrillo's existence or reach him for comment were unsuccessful.)

The persistence of such stories has also been helped along thanks to the popularity of the Netflix series Narcos: Mexico, which stars a heavily fictionalized - and rather sympathetic - version of Amado. In the third and final season, which became available on Friday, Amado takes center stage as the show follows a greatest-hits summary of his empire building and eventual fall from grace.

OMAR TORRES/AFP via Getty Images

In one of the final scenes, a moody Amado is shown prowling around the empty operating room prior to his surgery, and the narrator says outright that Amado has died. But then the show slyly drops an easter egg to superfans in the form of a final post-credits scene: As Amado's girlfriend wanders about in a seaside mansion, the camera cuts to a shot of a toy airplane that her lover had given her.

The myth has resonated for a reason in Mexico, where a toxic mix of authoritarian governance, pervasive corruption, a powerful criminal underground protected by the state and shrouded in lies and half truths has fueled a highly justified skepticism of any official narrative.

Here, for the first time, is the most complete account of one of the strangest chapters in the annals of Mexico's drug war.

Speaking publicly about the episode in detail for the first time, agents of the Drug Enforcement Administration who helped identify the body and confirm his death have laid out the full story behind one of the strangest incidents in the annals of the war on drugs.

Lord of the Skies

Like virtually every major drug trafficker of his generation - Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán Loera, Benjamín and Ramón Arellano-Félix, Ismael "El Mayo" Zambada García - Amado was a native of the northwestern state of Sinaloa, that long, thin state in Mexico's northwest whose western borders greet the waves of the Gulf of Cortez and whose eastern borders end in the highlands of the Sierra Madre Occidental.

It's a rugged, hardscrabble region populated by ranchers with weather-beaten faces and farmers who for the better part of a century represented the bottom rung of the marijuana and opium trade in the Western Hemisphere.

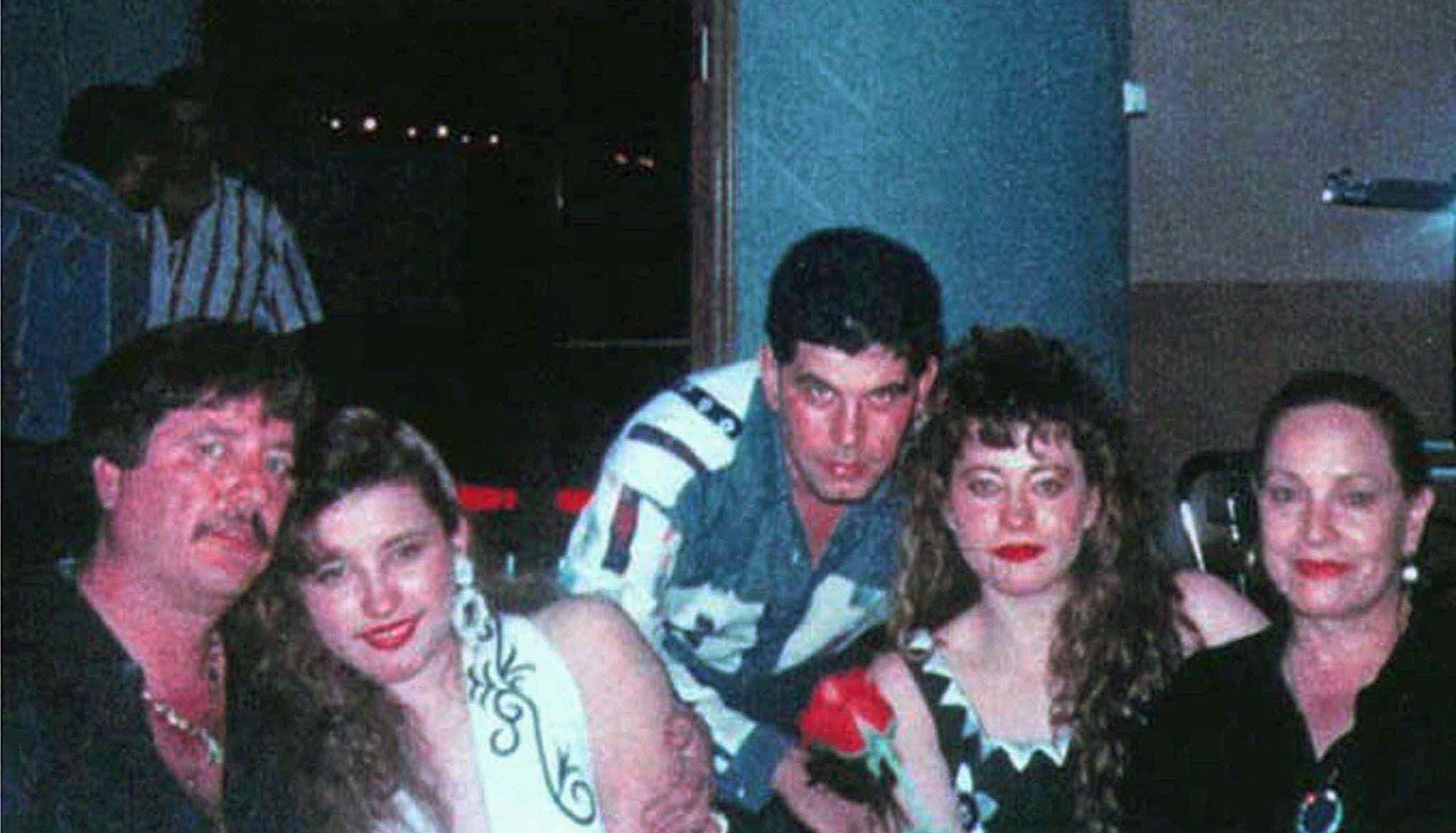

Amado and his 10 siblings grew up in a tiny settlement in the scrubland just north of Navalato, a tough little bread-basket town surrounded by fields of sugarcane, maize, and wheat.

Also like many of his fellow future kingpins, Amado's family had been involved in the drug business in one way or another since who-knows-when. It was a more humble business back then, small-time farmers selling opium and weed to small-time traffickers who brought the stuff north to the border. But thanks to the booming demand for marijuana in the late 1960s, and the shutdown in 1972 of the main pipeline for Turkish heroin from Europe to New York, Sinaloa's illicit economy became turbocharged.

Reuters

So it helped that Amado's uncle was one of those traffickers. A murderous brute of a man, Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo, better known as Don Neto, was by the 1980s a key partner in the trafficking network often referred to as the Guadalajara Cartel.

It was the advent of the cocaine boom, when Mexican traffickers began to branch out from weed and dope and made use of their existing smuggling routes to move Colombian cocaine, and the cash flowing back south twisted and perverted every facet of society.

Amado was an innovator in his own right, and is often credited as a pioneer of moving drugs by airplane, overseeing ever larger fleets of ever larger planes groaning under the weight of ever larger shipments of Colombian coke. This vocation earned him the nickname "el señor de los cielos," or the Lord of the Skies, and made him fantastically wealthy, with money to buy as many cops, judges, generals, and politicians as he needed to stay on the right side of things.

As the criminal landscape in Mexico shifted in the late 1980s following the breakup of the old guard in Guadalajara, Amado had relocated to Ciudad Juárez, a sprawling desert city just across the Río Grande from El Paso, Texas.

With its bustling border crossing that sees billions of dollars in cargo cross each way every year - an economic engine that leapt into overdrive with the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement - Juárez was the crown jewel in the constellation of smuggling routes into the United States.

The local capos who controlled the Juárez smuggling route, or "plaza," soon began to display a curious habit of dying, one after another. Amado, for his part, showed a talent for stepping out from the wings to claim their turf.

Ivan Pierre Aguirre/AP Photo

Amado was a skilled smuggler. He was also a brilliant manager with a head for politics, and he built a vast network of street enforcers, informants in every agency of Mexican law enforcement and military, and connections to powerful friends capable of easily quashing the political will to arrest him.

While other traffickers fought bloody turf battles and moved coke, weed, and heroin across remote border crossings in the desert, Amado was consolidating power and largely keeping the peace in Juárez, where he proved a reliable colleague to corrupt officials turned off by the ostentatious violence of his competitors. In a few short years, he had become the most influential drug trafficker in Mexico.

But even for a guy with the political savvy that Amado had in spades, remaining atop the tangled web of shifting alliances and competing priorities that dictate the status quo in Mexico was a deadly game, and any number of brand-name narcos who came before him had enjoyed that sweet spot for a time before they attracted too much attention and with it their own expiration date.

By the mid-1990s, Amado had become the most powerful drug lord in the country.

"A guy of absolute, unquestioned integrity"

Early in 1997, the balance that Amado had so skillfully maintained was thrown into a tailspin with the arrest of General Jesús Héctor Gutierrez Rebollo, Mexico's top drug warrior. He had worked closely with agents of the DEA to pursue trafficking networks and had the endorsement of many in Washington.

President Ernesto Zedillo had appointed the general to lead the fight against drugs as part of an effort to cut out the notoriously corrupt alphabet soup of police agencies in favor of the military, which despite its own legacy of corruption and human-rights abuses enjoyed a level of trust and respect that most other branches of the government had long ago squandered. Washington had enthusiastically supported the appointment, and General Barry McCaffrey, President Bill Clinton's drug czar, had praised the general as "a guy of absolute, unquestioned integrity" as recently as in December of 1996.

So the DEA and their higher ups in D.C. were shocked when, on Feb. 17, 1997, the general was suddenly dismissed, and even more so a day later when Mexican officials announced that Gutierrez Rebollo had been arrested for receiving payoffs from one Amado Carrillo Fuentes.

Reuters

As winter turned into spring, Guttierez Rebollo was sitting in irons, and Washington was sporting a deeply embarrassing black eye. At a hearing in March, DEA chief Thomas A. Constantine mused that major traffickers in Mexico "seem to be operating with impunity," and a congressional subcommittee convened soon thereafter to discuss slamming shut the faucet of foreign aid to Mexico.

The Mexican government has never reacted well to its frenemies in the drug trade catching the undivided attention of the U.S. government, as a long line of Amado's former compatriots found out the hard way.

And now the high-beams were focused on Amado. As one of the key public faces of drug trafficking in Mexico - and as the man whose bribes were the stated reason for the general's arrest - Amado found himself suddenly, dangerously exposed, and desperate to disappear, according to Ralph Villaruel, a retired DEA agent who was stationed in Guadalajara at the time.

"We were hearing he was in Russia, that he was in Chile," Villaruel told me in an interview. "We heard that he wanted to pay [the government] to be left alone, that he didn't want nothing to do with drug trafficking no more."

Amado was a wreck. Overweight and reportedly strung out on his own personal stash carved off the tens of thousands of kilos his men continued to smuggle north, he seems to have opted for a radical solution: he would alter his appearance with plastic surgery.

So on July 3, 1997, he used a false name to check into a hospital in a ritzy neighborhood of Mexico, and, in a heavily guarded operating room, the lord of the skies succumbed to a lethal dose of anesthesia and sedatives.

"We think Amado Carrillo Fuentes is dead"

Mauricio Fernandez wasn't getting much sleep in those days.

Fernandez, newly married, had been working at the Mexico City office of the DEA for about a year. He'd joined the agency in 1991 after serving in the Marines, and threw himself into his new vocation with a zeal inspired in part by the ravages of drug addiction he'd witnessed back home growing up in the Bronx.

A dedicated posting to the resident office in Mexico City should have brought a bit of stability to his life after having spent the past few years working in an elite unit with special-forces training, bushwhacking coca fields in the high Andes of Bolivia, raiding drug labs in the lush mountain valleys of Peru, and chasing down a Colombian rival of Pablo Escobar whose brilliance earned him the nickname "the Chessmaster."

Henry Romero/Reuters

But when he arrived in Mexico City, he was soon stunned by the level to which drug traffickers were entangled with the state at every level, from local cops on up to judges, military officers, and members of the political and business elite. It was hard to know who to trust. He was getting death threats.

"The deception was more sophisticated in Mexico," he told me in an interview. "The level of deception was so embedded that even for people you thought were vetted, even them you could not trust. There was no such thing as safe partnership."

Cooperation between the U.S. and Mexico on anti-drug policy was then and is now deeply fraught, riven with well-earned mutual distrust. But Fernandez and his fellow DEA agents had worked hard to build relationships with a few key members of Mexican anti-drug units, and it was starting to pay dividends. Through a contact in the Attorney General's office, or PGR, Fernandez and his partner had extensive access to sensitive information, and did their best to share intel with their counterparts.

Fernandez and his partner were the lead case agents on investigations into some of Mexico's most notorious drug traffickers, and they routinely pulled 80-hour weeks, living and breathing their work, sleeping at the office. They were investigating a handful of different drug-trafficking networks, but one man stood above the rest: Amado Carrillo Fuentes.

Getty Images

Most roads led to Amado in some way or another, or they led as close as the DEA could get anyway. Any time they thought they might be getting close, witnesses had a way of turning up dead, warning had a way of finding itself to their query, and Amado cruised along as always.

As he played the delicate game of political maneuvering necessary to survive in the underworld of Mexican organized crime, Amado was building a business empire of global proportions.

Even now, decades later, Fernandez still speaks of Amado with the grudging respect of a guy who knows the folly of underestimating one's enemies.

"It was a slap in the face to say that Amado was simply a drug trafficker," Fernandez told me. "His span was incredible. He touched Asia, he touched Europe, all parts of the world, and that's when you start to understand the vastness of his enterprise."

With a query like that, no, Fernandez wasn't sleeping much.

So when July 4, 1997 rolled around, Fernandez was looking forward to a bit of R&R, a chance to spend some time with his wife and shoot the shit with his colleagues and their families at the annual Independence Day bash at the ambassador's residence in Lomas de Chapultepec, a lavish neighborhood of rolling hills and the gated mansions of the Mexican elite.

But work found him anyway, as it often did, in the form of a call from a high-ranking Mexican law-enforcement official. It was one of the men with whom he'd spent the past year building up a cautious but increasingly strong rapport.

The ramifications of the news that came through the phone are still playing out today.

"We think Amado Carrillo Fuentes is dead," the official told him.

"All kinds of rumors are going to spring up"

The details were sketchy, no one knew for sure what to believe, but Fernandez' source told him what he could: the Lord of the Skies had the day before slunk into a private clinic in Mexico City for some kind of operation, maybe liposuction, maybe plastic surgery, and had died on the operating table.

Whether it was negligence or homicidal intent was unclear. ut word was, Amado was dead.

Those words hit Fernandez like a thunderclap. After hanging up, he sidled over to his boss and his boss's boss, who were standing about chatting and soaking up the unique glory of a Mexico City summer day. Fernandez pulled the two more senior agents aside and told him what he had just heard.

Before long, the news rippled out through the crowd and the DEA agents in attendance huddled up to figure out what do do next.

In the middle of that scrum was Larry Villalobos, a DEA intelligence analyst who'd arrived in Mexico the year prior after a stint in El Paso building dossiers on the major drug traffickers operating in Mexico. He knew everybody. To this day, Villalobos has the uncanny ability to summon up the names of men long dead and recall the bit-part roles they played in the larger action.

Reuters

At the ambassador's residence the party continued. But for Fernandez, Villalobos, and the rest of the DEA crew in attendance that day, there was work to do. They had a window in which they could confirm that Amado was dead and that window was already closing rapidly, Villalobos recalled.

"We knew from working in Mexico that if you wait any goddamn longer than that all kinds of rumors are going to spring up," Villalobos told me.

A fingerprint match

As they hustled away from the ambassador's residence, Fernandez, Villalobos, and the other DEA agents knew that the first thing they had to do was find the body.

According to the law-enforcement source Fernandez, by the time the DEA agents hightailed it away from their aborted Fourth of July party, the body was already on a plane en route to Sinaloa. But by the time it landed, a team of agents with the Attorney General's office were waiting.

They seized the casket and immediately put it on a plane back to Mexico City. According to an Associated Press report a few days later, the agents had to forcibly part Amado's mother from the casket that she clearly believed held the remains of her son.

Reuters

Some of the field agents began to press all their sources for information. But for Villalobos, who had worked as a fingerprint technician with the FBI before joining the DEA, it all came down to the body. And suddenly, he recalled an astonishing fact: the U.S. was in possession of Amado's fingerprints, taken by Border Patrol agents in Presidio, Texas way back in 1985 and later unearthed from the files of the Immigration and Naturalization service.

He got on the phone with his old intelligence office in El Paso, and had them overnight a set of the prints to Mexico City while a Mexican technician did his best to harvest a set from the corpse, which had long since gone stiff with rigor mortis. As the body decomposes after death, the quality of the available prints start to degrade, but after comparing the prints on file with those taken from the corpse, Villalobos was certain.

His boss wanted to know how certain he was that this was, in fact, Amado Carrillo Fuentes. Ever precise, Villalobos clarified the issue.

"I didn't say that it was Amado. What I said was that the fingerprints that were taken from a young man who resembles the Amado that we all know, and was fingerprinted as an illegal alien 20 years ago, is the same person as this corpse," Villalobos recalled telling the senior DEA attache in Mexico City.

Reuters

"Whether it's Amado or not, that's a different matter, but it would have had to been some type of conspiracy over 20 years that some guy was gonna die and they were gonna substitute the body of the guy who was in Presidio, Texas 20 years ago."

In other words, it was Amado.

The positive ID on the fingerprints that Villalobos made came no more than 72 hours after Amado died in surgery, but already speculation was buzzing about the possible death of the kingpin of Juárez.

While Villalobos had been doing his thing, other agents like Mauricio Fernandez had been working their sources and keeping in constant contact with trusted Mexican officials doing the same, and they were starting to get indications from the underworld that the big guy really was gone.

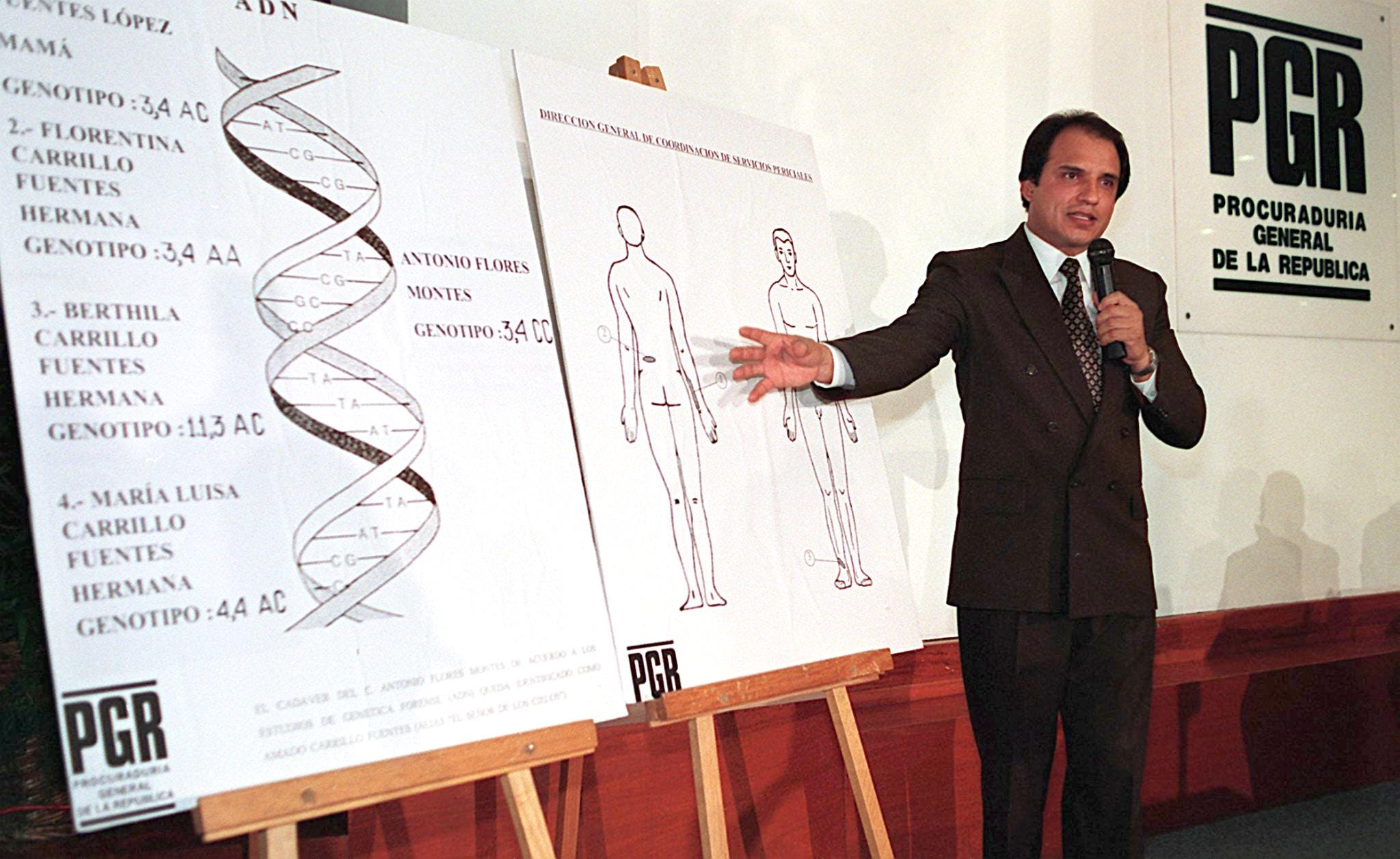

Meanwhile, in Mexico City, a forensics expert from Mexico's Attorney General's office held a press conference where he presented the fingerprint evidence.

"It would have made for a wonderful story"

After the confirmation from DEA, after the confirmation from the Mexican government, after the body was returned to Amado's family and buried in his hometown of Guamuchilito, Sinaloa, the myth of Amado's survival began to grow, and it has never really gone away. Even now, Fernandez said he understands why the myth of Amado has clung on for so long.

"There was a lot of folklore around Amado and who he was, and I think for a lot of people, they wanted to keep that thought alive," Fernandez said. "It would have made for a wonderful story, but the fact is that that wasn't the case. It just was not the case."

Reuters

Regardless of where one stands on the fact that Amado Carrillo Fuentes died in July 1997, no one disputes the fact that his death was a turning point, one of the periodic tectonic shifts throughout the history of the war on drugs in Mexico.

Amado's younger brother Vicente took the reins, but he didn't have it in him, and people didn't respect him the way they had Amado. The alliances that Amado held together soon started to fray, and that breakdown helped contribute to the staggering wave of violence that washed over Mexico a decade later and has yet to truly recede.

This dynamic within Amado's network may have played a part in the myths that sprung up so soon after his death. With a weak leader like Vicente running the ship and its increasingly mutinous crew aground, the idea of a vengeful Amado out there, maybe coming back some day, might have been useful for keeping people in line, according to Jesús Esquivel, a veteran Mexican journalist who was one of the first reporters to break the news of Amado's death.

XAVIER MARTINEZ/AFP via Getty Images

"Vicente was weak, and the local criminals knew, and they said 'this is our time,'" Esquivel told me. "So they were playing with Amado's shadow."

Larry Villalobos, for his part, still hears the old conspiracy theories from time to time, occasionally from unlikely sources.

"I had an FBI agent come up to me less than 10 years ago and he says to me 'what if I told you Amado was still alive?'" Villalobos told Insider. "I was like 'get the fuck outta here, I don't wanna hear that shit. I saw the fingerprints, I made the identification, what are you talking about?"

According to Villalobos, the FBI agent was insistent, telling him that a trusted source had recently claimed to have spotted Amado in his old stomping grounds of Ojinga, just over the border from Texas. Even better, the source claimed to know where exactly they could find him.

Villalobos was not moved.

"I hope the FBI didn't pay too much for that tip," Villalobos said.