Can a machine tell that you're mad just by looking at your face? Do your emails give away how stressed you are? Could a computer understand your emotions better than you?

According to a wave of new startups, the answer to all of the above is a resounding yes. A raft of companies is trying to sell the idea that emotion artificial intelligence can pick up on subtle facial movements that we aren't even aware we're making, use those minuscule twitches to determine what we're feeling, and then turn those private feelings into quantifiable data. EAI, the developers claim, can pick apart the differences between emotions such as happiness, confusion, anger, and even sentimentality. In theory, this tech makes it possible for a computer to know our emotions — even if we don't know them ourselves.

For companies, EAI may be a gold mine. Being able to understand customers' genuine thoughts, feelings, and personalities would make it a lot easier for companies to sell their products. Imagine you're browsing on a shopping app and you don't like what you're seeing. With EAI, the app could tell in an instant and quickly serve up the kind of content that it thought would make you feel good — and be more likely to buy. Some businesses are already using the tech to make smart toys, robotics, vehicles, and empathetic AI chatbots. Beyond commercial uses, EAI could help companies in the workplace: Knowing the emotional state of a prospective or current employee can help companies make decisions that improve productivity and keep things humming along.

But there's a catch: It's not clear that EAI even works. The science behind the tech is disputed by experts in the field, and some critics say that understanding how we feel by examining our facial expressions isn't possible. But that isn't stopping companies from using EAI to spy on their employees, determine how they feel, and identify who should be hired and who should be fired. AI is poised to influence all parts of the workforce, but this may be one of the most insidious. Without us even realizing, our bosses could be guessing our private emotions — and using them against us.

How it works

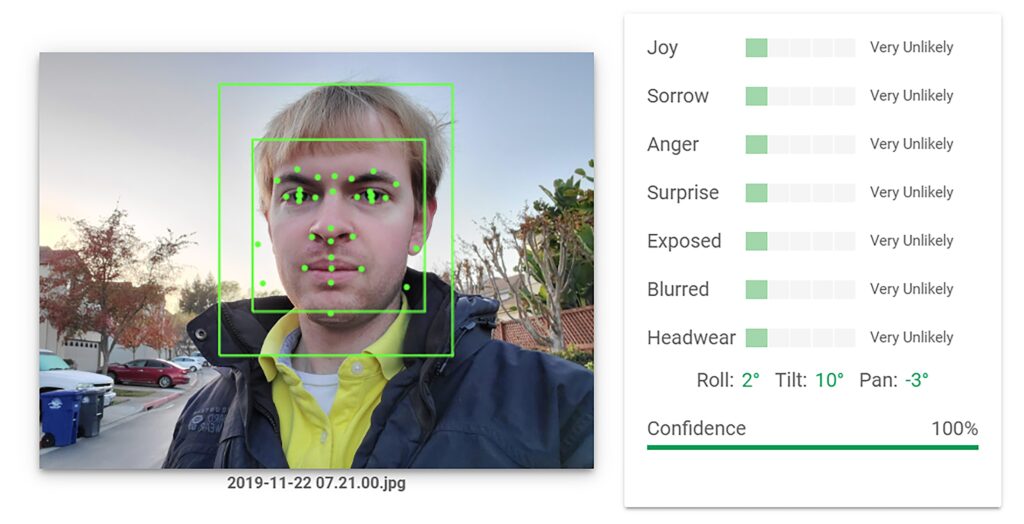

While versions of emotion AI have been in development since the late 1990s, the industry has taken off in recent years as the underlying tech that powers the AI has become more sophisticated and interest in the field has increased. Today, the amount of data that EAI can be trained on is overwhelming. Companies use the tech to measure things including breathing, heart rate, perspiration, changes in the electrical conductance of our skin, and body posture. That data is then used for a wide variety of applications, such as detecting when someone may be lying about insurance claims, helping diagnose depression, and tracking how students are responding to a teacher during online learning. Some versions of EAI are focused on verbal cues, tracking tiny conversation pauses and tonal shifts. Others take into account changes in pupil dilation and gaze. There are also models that can read your emails, texts, or other messages, and generate in-depth reports on what underlying emotions you may be unconsciously expressing.

Gabi Zijderveld, the chief marketing officer of Smart Eye, an EAI company that claims its tech "understands, supports, and predicts human behavior," said the firm had amassed vast amounts of emotion-based data by analyzing over 14.5 million videos of facial expressions it made with voluntary participants. She described its AI as "basically looking at the human, looking at facial-expression analysis, people's movement, people's nonverbal cues — as we like to say — to understand what their emotional and, perhaps, cognitive state is."

Smart Eye uses this tech for things such as driver-monitoring systems that detect driver fatigue using a mixture of facial analysis and eye tracking. It also provides analytics for advertising and entertainment companies. In these cases, paid participants watch online videos, and their facial expressions are analyzed by EAI technology to determine whether a joke in an ad was funny or whether a particular moment in a movie trailer elicited the emotional response it was meant to. (Zijderveld emphasized that participation in these test groups was always optional.) The company then uses that data — combined with demographic information participants provide — to, Zijderveld said, "start segmenting how different populations are reacting to that content."

Companies like CBS and Disney can use this information to tailor their products based on how people are reacting to them. Maybe they recut a trailer, get rid of a joke that's not landing, or change an ad based on the demographics of the audience they're selling to.

Monitoring employee emotions

While those applications may seem benign or even beneficial, the use of EAI in the workplace is much more fraught. Employees often don't realize it's being used, meaning they could be deemed unhappy at work, emotionally unstable, or too stressed to do their job without even knowing they were being surveilled in the first place.

HireVue, a Utah recruitment platform, began using EAI facial analysis in 2014 as part of its candidate interview process. The idea behind the tech was noble: The EAI was supposed to mitigate bias and spot ideal candidates by identifying soft skills, cognitive ability, psychological traits, and emotional intelligence during video interviews. Hundreds of businesses, including Ikea, Dow Jones, and Oracle, used the software to assess more than 1 million job seekers, The Washington Post reported. But in 2019, a complaint by the Electronic Privacy Information Center alleged "unfair and deceptive practices" because HireVue's tech was not proven to be able to do what the company said it could. The complaint pointed to research that found facial analysis could be biased against women, people of color, and people with neurological differences, and argued that it shouldn't be used to make hiring decisions.

Employees frequently remain unaware that their company is using the tech while they're on the job.

In response to public outcry, the company said in 2021 it would stop the use of EAI facial analysis because it wasn't worth the concern but would continue analyzing speech, intonation, and behavior during interviews. According to the company, the verbal elements were enough to make conclusions about a candidate's emotional state. "Algorithms do not see significant additional predictive power when nonverbal data is added to language data," it said.

Other recruitment platforms, such as Retorio, a Munich "behavioral-intelligence platform," use a combination of facial analysis, body-pose recognition, and voice analysis "to create a personality trait and soft skill profile of candidates, allowing recruiters to make smarter sales recruitment decisions," the company's website says. It also says that its tech removes bias and that the process is voluntary for candidates, who can opt out at any point before the video recording is sent to the hiring company and apply a different way.

Sarah Myers West, the managing director of the AI Now Institute, is skeptical of company claims that EAI is free of bias. "There's no scenario where you can go around making that kind of claim with any rigor," she said. And while Retorio may emphasize the voluntary nature of its tech, the companies who license it could be discounting candidates who choose to not submit a video interview.

Once hired, workers aren't free of emotion-recognition tech. In call centers, EAI is already being used to pick up on the emotions of customer-service representatives and the customers on the other end of the line. It can give real-time feedback to workers on how they should adjust their tone to align with what the algorithms consider appropriate. This left some workers feeling confused by negative feedback and scared that the tech would get them in trouble if they didn't sound sufficiently positive, researchers found.

And other companies are racing to develop EAI-enabled gadgets to dig even deeper into employees' psyches. Framery, a company that makes high-end office pods used by the likes of LinkedIn and Nvidia, has recently started testing an office chair embedded with biosensors. "We can measure heart rate, heart-rate variability, breathing rate, and the nervousness of the people," the Helsinki-based founder Samu Hällfors said. Framery has also patented a tool to measure laughter based on just body movement. Hällfors envisions that businesses will soon include employee well-being metrics in their corporate reporting. If that happens, Framery will be able to step in and anonymously compile data from its smart chairs to help companies determine the overall sentiment of their workplaces — and track when staffers are more stressed.

But West has questioned claims of keeping emotional data anonymous: "You're dealing with identifiable data inherently if you're working with biometrics and emotion recognition." She added, "There's so many data streams that are being collected that the anonymization claim really breaks down."

There's so many data streams that are being collected that the anonymization claim really breaks down.

The founders of Looksery, a photo and software company owned by Snap Inc., were granted a patent in 2017 for videoconferencing technology referred to as "Emotion Recognition For WorkForce." While it's unclear whether it's being used, the patent covers emotion recognition for video calls, especially for call-center workers, and says unambiguously that "an employer can use this information for workforce optimization, laying-off underperforming employees, promoting those employees that have positive attitudes towards customers, or making other administrative decisions."

Kat Roemmich, a Ph.D. student at the University of Michigan School of Information who has conducted research on EAI, has found that employees frequently remain unaware that their company is using the tech while they're on the job. In fact, there's no requirement for employers to tell them. Emotional information can be gathered by "analyzing data that they already collect as part of existing monitoring and surveillance programs," Roemmich said, meaning companies can just tack EAI onto existing surveillance programs without alerting employees.

The rapid expansion of surveillance programs during the pandemic because of remote work has left more people exposed to the possibility of having their emotions tracked at work. Since EAI is not considered uniquely identifiable biometric data — the way a fingerprint or facial scan is — it's unregulated in the US. In Europe, the EU is working on a bill that would likely make it illegal in the workplace. But until there's regulation, companies are free to use it as they please.

Pseudoscience?

In addition to the ethical problems of EAI, the tech faces another challenge: It may not even work. EAI that interprets facial expressions is often rooted in the American psychologist Paul Ekman's research, which proposed that core human emotions — fear, anger, joy, sadness, disgust, and surprise — were revealed through universal facial expressions transcending cultural differences. But Ekman's work has faced substantial pushback in recent years, and there's no consensus among scientists on the definition of specific human emotions, or how you could accurately read them on someone's face.

A 2019 review of the available research on emotion recognition through facial analysis found that there was insufficient evidence for any link between facial expressions and emotions. The paper's authors wrote: "Very little is known about how and why certain facial movements express instances of emotion, particularly at a level of detail sufficient for such conclusions to be used in important, real-world applications." They also pointed out that different contexts and cultures could result in a huge variety of expressions for the same emotion.

There's no consensus among scientists on the definition of specific human emotions, or how you could accurately read them on someone's face.

EAI companies disagree. Zijderveld of Smart Eye said that the company's vast amounts of data from about 90 countries "allows us to account for these cultural sensitivities." She added that knowing context was clearly important to understanding the correlation between emotions and facial expressions.

But the industry's opaqueness makes it nearly impossible to obtain independent research-based proof of how the tech works. "It's a sticking point for me," Roemmich said. "If we can't get the framing of the debates right and the foundational issues, then, as we're already seeing, practitioners that use emotionality are going to disregard it."

Even if the tech can genuinely capture internal feelings, using it in work settings gives companies unprecedented access to the private emotions of their employees. And if it can't, then companies using EAI to make decisions about hiring or firing someone could be entirely misguided. Either way, it's a troubling indication of how companies are creeping into every part of our lives — even our innermost thoughts and feelings.

Clem De Pressigny is a freelance writer and editor, and previously the Editorial Director of i-D magazine. She covers the internet and technology, the climate crisis and culture.