- We have full employment in the US and the UK but extremely low wage growth.

- The “gig economy” is structured to keep wage levels down even when there are shortages of workers.

- Underemployment – part-time work – has replaced the role that mass unemployment used to play in the US and the UK.

- Work now creates inequality, and workers know they cannot get ahead merely by working.

- That has political consequences: It makes the minimum-wage level one of the most important political issues.

Troy Taylor, the CEO of the Coca-Cola franchise for Florida, was asked at a recent conference of the Federal Reserve’s Dallas branch whether he expected pay raises in the future. The context to the question is that America has ultralow unemployment. In fact, it has even reached what policymakers consider to be full employment, in which essentially everyone who wants a job has one. Wages ought to be rising as workers take advantage.

But Taylor said he didn’t see wages going up anytime soon. “It’s just not going to happen,” Taylor said. “Absolutely not in my business.”

The reason Taylor can be so confident is that employers – and, belatedly, economists – are waking up to the fact that the old-fashioned supply-and-demand model of the labor market is dead. Employers have gained enough power in the marketplace to permanently hold down wages, even when unemployment is as low as 3.9% in the US and 4.2% in the UK.

The old model was simple. It stated that the price of labor was set by supply and demand. If the supply of workers was restricted, wages would inevitably rise as workers switch jobs for better-paid positions or negotiate pay raises for staying.

Right now we are living through the most supply-restricted wage market since the 1970s. There just aren't extra workers available. In the US, there are 6.7 million job openings but only 6.3 million people looking for work, according to the most recent government numbers.

'I ain't gonna work on Maggie's farm no more' ought to be the national anthem

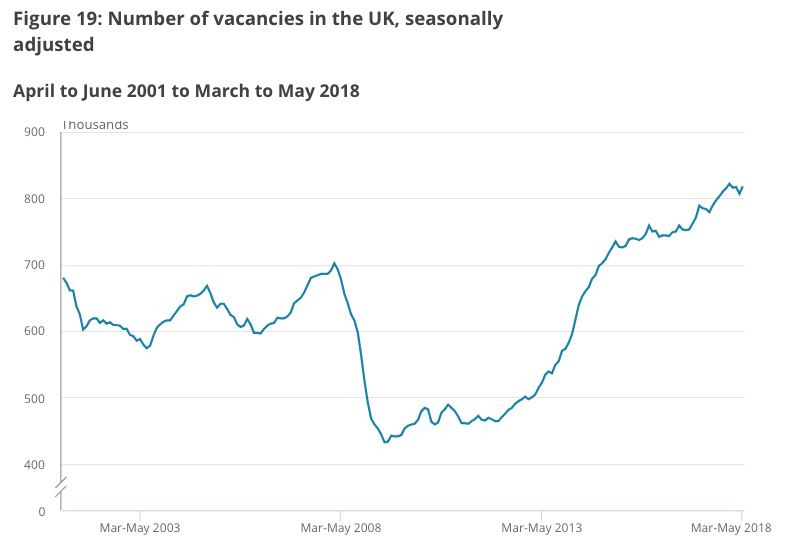

Job vacancies in the UK are also at a record high.

So this ought to be a golden age for workers. Wages ought to be going up. Employees ought to be able to name their price. "I ain't gonna work on Maggie's farm no more" ought to be the national anthem.

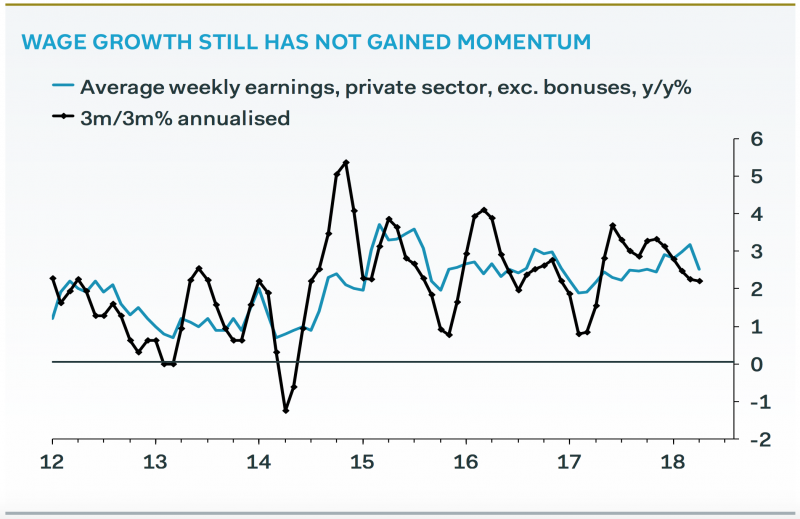

And yet, in the US and the UK, wages are stagnant.

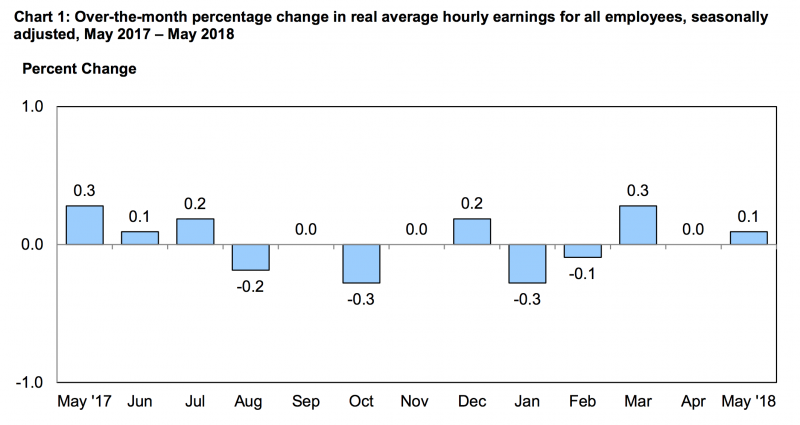

In May, wages for workers in the US rose just 0.1%.

'We have not experienced anything like it for at least 150 years'

It's a similar picture in the UK, where year-on-year wage growth is about 2%. That's roughly the same as inflation, meaning that real wages are flat.

Economists are starting to wake up to this strange phenomenon.

Paul Johnson, the director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, wrote recently: "Astonishingly, real wages remain well below where they were a decade ago. We have not experienced anything like it for at least 150 years."

'The competitive supply-and-demand model of labor markets is fundamentally broken'

Noah Smith, writing for Bloomberg, believes, "Together with the evidence on minimum wage, this new evidence suggests that the competitive supply-and-demand model of labor markets is fundamentally broken."

And Martin Beck, the lead UK economist at Oxford Economics, noted that April's average pay increase was the weakest rise since November. He told clients recently, "But that the economy has reached 'full employment' was hard to reconcile with a slowdown in average pay growth."

After inflation, some people's pay is in decline. David Frum, the Republican political writer, tweeted recently:

Hourly wages for nonsupervisory workers are lower than 1 year ago, after adjusting for inflation induced by Trump trade wars and trillion-dollar budget deficits https://t.co/LYYZBzp8MK

— David Frum (@davidfrum) June 16, 2018

Uber, Just Eat, and Deliveroo can switch their demand for labor on and off on a minute-by-minute basis

As I've noted before on Business Insider, the part-time gig economy has broken a fundamental link in capitalism that was good for workers. Pay rates no longer move upward as unemployment moves downward because companies like Uber, Just Eat, and Deliveroo can switch their demand for labor on and off on a minute-by-minute basis. Self-employed folks making a living on Etsy, Amazon, Airbnb, or eBay know their clients instantly go elsewhere if they raise their prices by even a few pennies.

Unemployment is low because a massive number of new jobs today are part-time gig-economy jobs. Part-time "underemployment" has, statistically replaced the mass unemployment we remember from the 1980s. As Johnson says: "A majority of people who are classified as poor now live in a household where someone is in work. This is a complete turnaround from 20 years ago when two-thirds of the poor lived in workless households."

In other words, in the old days when you lost your job you claimed unemployment benefits and lived "on the dole." Today, you deliver pizzas or stuff packages in an Amazon warehouse for 20 hours a week.

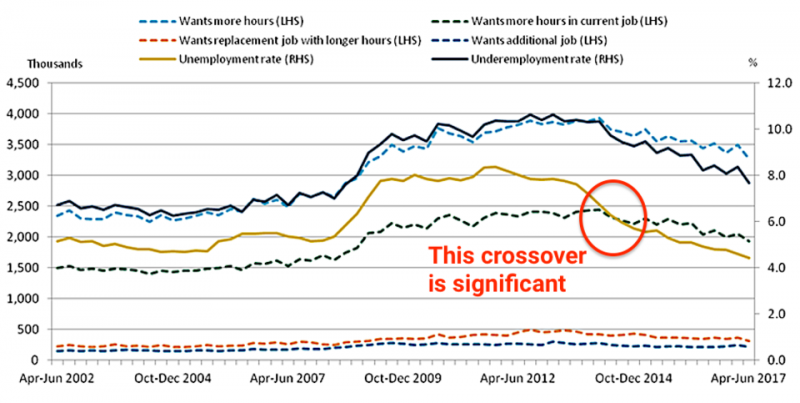

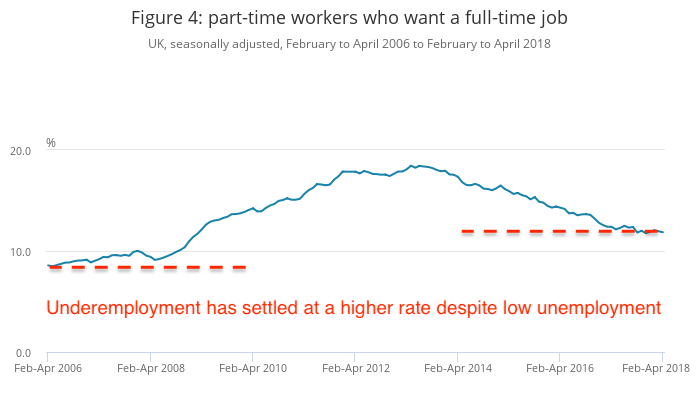

This chart from the ONS in the UK (below) shows how part-time work has replaced the role that mass unemployment used to have. The number of workers who want more hours is higher now than before the 2008 crisis even though unemployment is lower:

John Robertson of the Federal Reserve's Atlanta branch has some data here showing the same thing in the US: "The upshot is that for each unemployed worker, there are now many more involuntary part-time workers than in the past."

'The unemployed' now barely exist - and this has political consequences

Underemployment seems to have settled at a permanently higher level than it was a decade ago.

This has obvious political consequences.

Working is no longer a guaranteed way of getting ahead. Instead, it may keep you poor. You cannot get rich working for Uber. You cannot get rich working for Deliveroo.

The obvious function of the so-called gig economy is to create inequality. "The unemployed" now barely exist. In their place are millions of people stuck in jobs that offer too few hours to get by or jobs that don't come with a career ladder offering pay advancement.

In that context, the minimum wage suddenly becomes the most important political issue for workers. It's the only way to get a raise in an economy that does not create full-time jobs or jobs with regular pay increases.

Politicians used to blame the unemployed for being insufficiently ambitious. Unemployment was regarded as the fault of the unemployed. President Ronald Reagan excoriated "welfare queens." In the same era, Norman Tebbit, then the UK employment secretary, once infamously suggested that unemployed people should simply get on their bikes to look for work.

Today everyone has work, yet work no longer offers a ladder out of poverty for people willing to climb it.

From that perspective, the rise of politicians like President Donald Trump, the Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, and the 2016 US presidential candidate Bernie Sanders seems unsurprising: In one way or another, they all represent the frustration of workers for whom work is no longer worth it.