The sharp and steady increase in US inequality in recent decades has been well documented. Less attention has been paid to a potentially even more important and alarming trend – a decline in US social mobility.

After all, this is the very essence of the American Dream, that people can succeed and prosper if they just work and try hard enough. A startling decline in the ability of Americans to climb up the social ladder is documented in a new study published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

The report, entitled “The Decline in Intergenerational Mobility After 1980” finds “mobility declined sharply for cohorts born between 1957 and 1964 compared to those born between 1942 and 1953.”

Why the distinction? “The former entered the labor market largely after the large rise in inequality that occurred around 1980 while the latter entered the labor market before this inflection point,” write Jonathan Davis of the University of Chicago and Bhashkar Mazumder, a Chicago Fed economist.

They find that “share of children whose income exceeds that of their parents fell by about 3 percentage points” in the period staring in 1980.

Their findings echo a study from the St. Louis Fed in March that showed US social mobility is much lower than its rich-country peers'.

An excerpt from the Minneapolis Fed paper sheds light on the importance of understanding social mobility when studying US inequality, which is now at levels comparable to the Great Depression (emphasis ours):

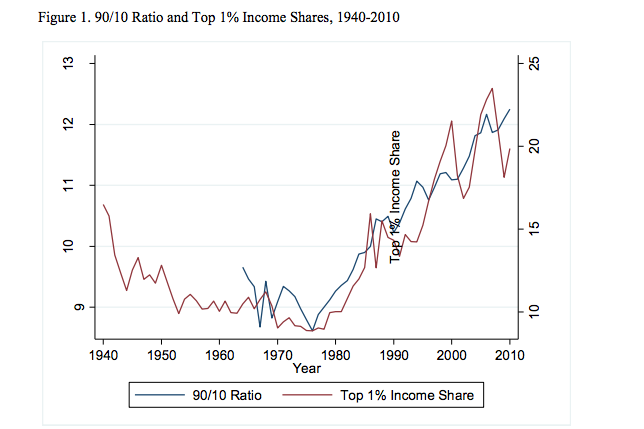

"One of the most notable changes in the US economy in recent decades has been the rise in inequality. A key inflection point in inequality appears to be around 1980. It was during the early 1980s that there was a pronounced increase in the 90-10 income gap and a sharp rise in the income share of the 1%.

"With the advent of a more unequal society, concerns about a possible decline in inequality of opportunity have risen to the forefront of policy discussion in the US. To better understand inequality of opportunity, economists and other social scientists have increasingly focused attention on studies of intergenerational mobility. These studies typically estimate the strength of the association between parent income and the income of their offspring as adults."

In other words, it's not so much inequality of outcomes that bothers Americans, but inequality of opportunity. And that, unfortunately, appears to still be rising.