If you move into a new neighborhood being constructed outside of Amsterdam, your salad greens might come from the greenhouse attached to your home. Your eggs could be gathered from the village chicken coop, and your food waste would all get harvested for compost.

ReGen Villages is a startup real estate development company aiming to build small, self-sustaining residential communities around the world. The first one is expected to be completed in Almere, Netherlands in 2018. Unlike traditional subdivisions, ReGen villages would be “regenerative” (hence the name), since they’d use resources in a closed loop.

“Regenerative means systems where the output of one system can actually be the input of another,” ReGen’s founder, James Ehrlich tells Business Insider.

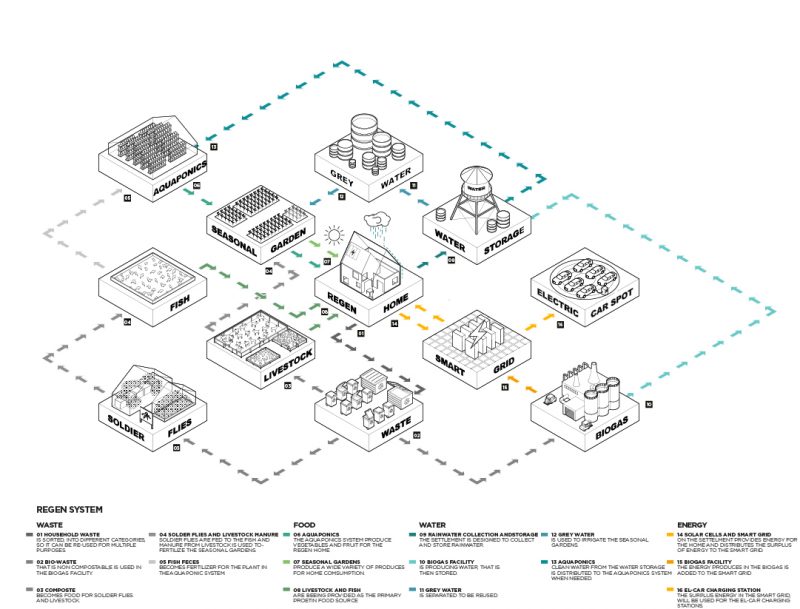

In ReGen villages, household food waste is composted and fed to flies, which in turn feeds fish, which then fertilizes aquaponic gardens (multi-layered systems that combine fish farming and hydroponic agriculture, with plant roots submerged in nutrient-rich solution rather than soil). Those aquaponic farms grow produce for residents to eat, as do seasonal gardens, which are be fertilized by waste from livestock raised to feed residents. Rainwater is harvested and filtered for use in the farms and gardens, and on-site solar panels power the homes.

Though this kind of regenerative, self-sufficient neighborhood might sound like a pipe dream, ReGen has already determined its first two sites. Ehrlich says he expects to sign a memo of understanding for a plot of land in Lund, Sweden in the coming weeks - the agreement will outline the intent to purchase the land and set forth initial terms. And ReGen's first site in the Netherlands is currently undergoing archaeological testing to make sure the village won't be built on top of any historic ruins.

Ehrlich expects to break ground there in the first quarter of 2017, begin construction by the end of the summer, and have the first 25 homes built by the end of the year.

Each completed village will house 100 families on about 50 acres. Each family's house will have an attached greenhouse for growing personal crops, and the village's communal farms and livestock will be managed and run by ReGen staff. Individuals can pitch in their labor as a way to lower the monthly fees homeowners pay on top of their mortgages. (In the Almere community, Ehrlich expects that cost to be around $560.)

"It's this concept that the way you look at a subdivision is edible, so you walk through the path and there's berries and fruit trees and nuts and spices and all kinds of things to enjoy," Ehrlich says. "We don't do lawns, we don't do golf courses or tennis courts. That's a good place to grow food, so we're going to grow food there."

Ehrlich refers to ReGen as the "Tesla of eco-villages," because he says the neighborhoods will allow eco-conscious people to elegantly go off the grid on their own terms. The villages will also use sensors and technology to monitor energy use, farming efficiency, and living patterns, and send that data to the cloud so villages in similar geographic regions can learn from each other. The strategy is similar to the way Tesla uses machine learning to analyze data gathered from the autopilot systems in its cars.

ReGen, which was founded in 2015, has partnered with Copenhagen-based architecture firm Effekt to design all the villages. Ehrlich says he hopes to build many more than the two that are already in progress - he's in discussions about buying sites in Denmark, Norway, Germany and Belgium.

Ehrlich says the ReGen villages are designed to give people an environmentally friendly alternative to urban life. He also hopes they can help make agriculture more sustainable and less wasteful.

He envisions these communities as disaster-resistant as well, since they could likely continue running if the current grid were compromised. He mentions Superstorm Sandy as an example.

"My family was without power for three weeks, and it got real after about three days," he says. "You run out of food, and your credit card doesn't work, and even if you have cash, you go to the supermarket and the shelves are bare. It doesn't take long for civilization to collapse, for there to be chaos."

Not every village could produce enough food or harvest enough water to satisfy all of its residents, of course. Ehrlich says the percentage of the nutritional needs the village could fulfill will depend on the climate in a given place (a farm in Hawaii could produce more year-round food than one in Sweden), as well as what the residents have come to expect to eat (imported delicacies, processed food, etc).

But Ehrlich's initial estimates are optimistic - he says a village could produce enough fresh food to take care of 50-100% of the needs of its residents.

And if there's any excess food or energy gathered, he says, that could also be sold, and the profits could offset residents' fees.

Ehrlich's next step is to firm up the designs for the different houses that prospective buyers will be able to purchase in the Netherlands. Then he can start compiling the initial list of people who are seriously interested in moving in.