- Kenya is home to many of the best marathon runners in the world.

- It’s no coincidence. Many of these world-class runners come from Iten, the “city of champions,” a town that sits on the edge of Rift Valley, 7,000 feet above sea level.

- Scientists and runners have questioned how they keep winning.

- Harvard biologist Daniel Lieberman, who studied the evolution of running, told NPR it was impossible to quantify – it’s a mixture of factors like training, culture, biology, and the runner’s determination.

- What used to be an unknown region is now a mecca for runners from around the world due its repeated successes.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Kenya’s Rift Valley is a mecca for running champions.

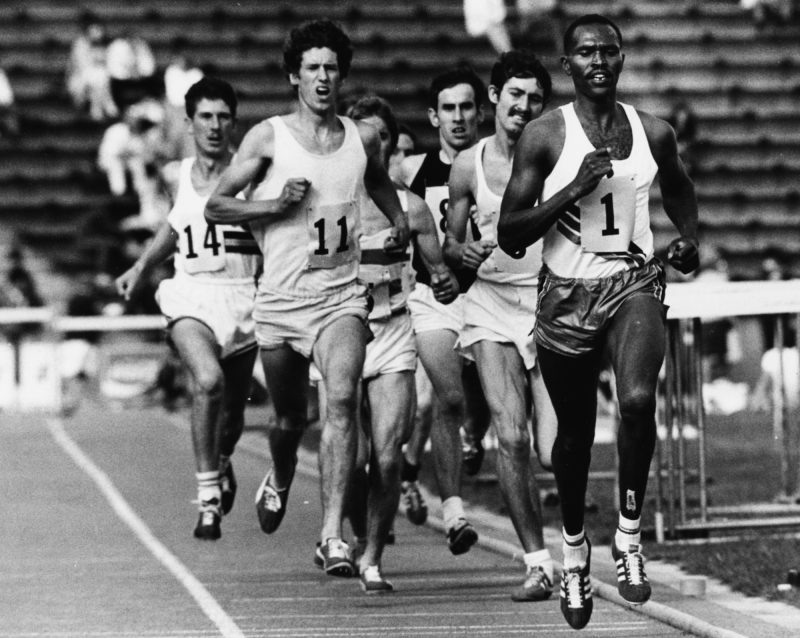

For decades runners from Kenya and Ethiopia have been dominating distance races. From 1968 onwards, Kenyan athletes have been a force to reckon with.

And what’s intrigued runners and experts is that so many champions come from, or train at, Rift Valley in Kenya. In particular, the town of Iten, which sits on the edge of the valley 7,000 feet above sea level, has produced so many marathon runners that it’s known as “the city of champions.”

But there’s no clear factor for the region’s repeated successes. It’s a variety of things like altitude, training, culture, and runners’ determination.

One thing's for sure - from an early age, local children watch runners crowd the streets and dream of following in their footsteps. A successful career as a distance runner is a way out of poverty.

Here's what Rift Valley is like.

Welcome, the sign says, to Iten, a small town on the edge of a plateau on Rift Valley in Kenya that's home to many of the best runners in the world.

Source: Independent

Rift Valley, which began forming about 40 million years ago, at times reaches 7,000 feet above sea level. Up there, it's flat, with mild temperatures ranging from 50 to 80 degrees Fahrenheit all year round, meaning it's perfect for marathon training.

Source: South Florida Sun Sentinel

Kenya has 50 million people, but only a fraction of the population is responsible for the country's sporting successes. It's mostly runners from Rift Valley who have gone on to dominate marathons for decades.

Source: CNN

The latest example of this was on Sunday, when the male and female winners of the New York Marathon were both from Kenya. Geoffrey Kamworor won his second title and Joyciline Jepkosgei won her first. They continued a tradition that's been going since 1968.

Source: CNN

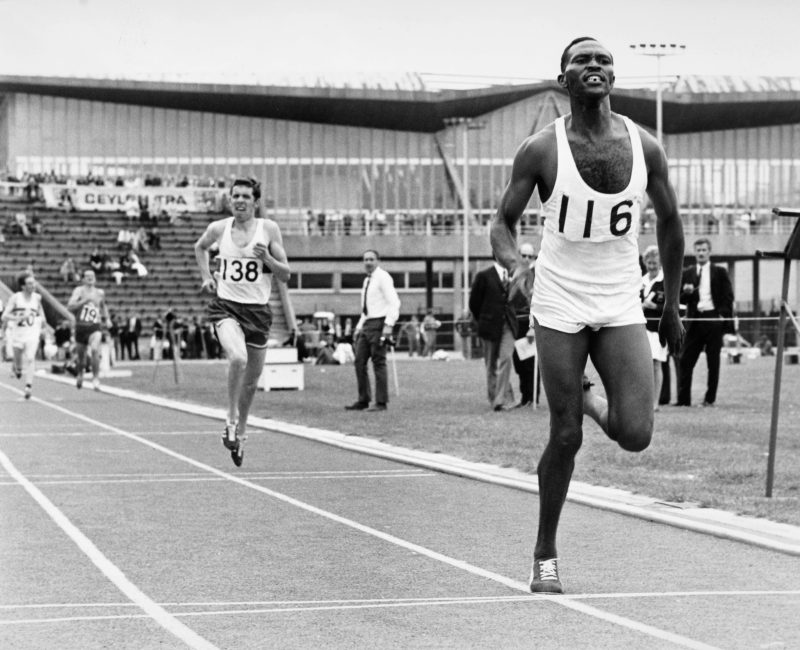

It began with unknown runner Kip Keino, who ushered in a new age of running for Kenya when he won gold in the 1,500 meter at the 1968 Olympics, despite having a gallbladder infection. It was the first of many medals to be won by runners from Rift Valley, and it helped turn the world's gaze to the region.

Sources: South Florida Sun Sentinel, Independent

When Keino began training to be a distance runner, it was out of the norm. His neighbors and peers thought he was chasing the wind, or that he was a madman, but he knew what he was doing.

Source: South Florida Sun Sentinel

He went onto win gold in 1972 as well, and his success began to catch on. Soon his neighbors were silver medalist Peter Koech and three-time steeplechase champion Joshue Kipkemboi.

Source: South Florida Sun Sentinel

After Keino, came winner after winner. Between 1988 and 2012, 20 out of 25 male winners of the Boston Marathon were from Kenya. In October 2011, after the Berlin Marathon, sports writer David Epstein said the statistics were laughable. "There are 17 American men in history who have run under 2:10 in the marathon. There were 32 Kalenjin who did it in October of 2011," he said.

Sources: CNN, The Atlantic, NPR

For Kenyan women first win was in 2000. The Atlantic's Max Fisher said this discrepancy could have been be due to discriminatory laws and forced marriages. But after the country's reforms, Kenyan women won nine marathons between 2000 and 2012. Here's Pamela Jelimo, the first Kenyan woman to win gold at the Olympics when she was 18.

Sources: The Atlantic, Independent

All this success by different people from the same region, led many to wonder what it was about Rift Valley that made so many of these runners the world's best, year after year.

In 1990, Copenhagen Muscle Research Center compared school boys from Iten to Sweden's national track team and found they consistently did better than the professionals.

Sources: The Atlantic, Active

That same study found that Kalenjin people from the region could outrun 90% of global population. The Kalenjin tribe is often mentioned in regards to marathon winners, because about 73% of Kenya's Olympic medal winners are from the Kalenjin tribe. There are about 4.5 million members of the Kalenjin tribe.

Sources: The Atlantic, Active, CNN

Later controversial research said the reason for all of the success was genetics, but Keino condemned the research as racist. "There's nothing in this world unless you work hard to reach where you are, and so I think running is mental," he said.

So it's remained a question without a definitive answer. Brother Colm O'Connell, an Irish missionary who started training his high school students to be runners even though he had no sports background, told the South Florida Sun Sentinel that he didn't know.

Sources: South Florida Sun Sentinel, CNN, ABC

O'Connell, who has been called the "godfather of Kenyan running," watched 25 of his students become world champions, and four win Olympic gold medals.

Source: Australia Broadcasting Corporation (ABC)

"The only secret is there's no secret," author Adharanand Finn quotes O'Connell saying. "It's not one thing but a perfect storm of elements that come together in Kenya's Rift Valley region to make the people there so strong at distance running."

Sources: South Florida Sun Sentinel, CNN, ABC

O'Connell also said it helped that it wasn't an expensive sport. He told ABC, "you don't need anything to be a runner. Even as young kids they run barefoot — you don't even need a pair of shoes."

Harvard evolutionary biologist Daniel Lieberman, who has studied the evolution of running, said something similar to NPR. It was impossible to quantify what made one runner better than another, he said. Instead, it's a mixture of things like training, culture, biology, and the runner's determination.

Source: NPR

Lieberman said young people from the valley only had two options — work on a farm or become a runner. And even if they train to be a runner, it's not easy. They get "no goo, no gel, no sports drinks," he said.

Sources: NPR, The Guardian

What they get is to see roads filled with world champion runners every day. People like British Olympic champion Mo Farah travel to train in the Rift Valley. He's been traveling there since 2008, and when he's training, he can run 140 miles a week. On his rest day he only runs 10 miles.

Source: The Guardian

The terrain is a factor. Runners train on dirt roads and rolling hills, as well as one challenging route known as "the big dipper," which is a steep hill that goes for a mile. Farah told The Guardian running in Rift Valley was like driving on bumpy terrain. "Instead of going 50mph, here you are just driving at 25mph and holding the steering on some bumpy road. Your legs and your body feel that," he said.

Sources: CNN, The Guardian

The high altitude play a key role. Three scientific studies found training in high altitudes improves running performance when the runner is down at sea level. This is because when the runners are down at sea level the air is thicker air and gives them a boost of oxygen.

Sources: CNN, The Atlantic

But there are lots of places with high altitudes around the world, like the Mexican Andes and Nepal, so it's not that alone.

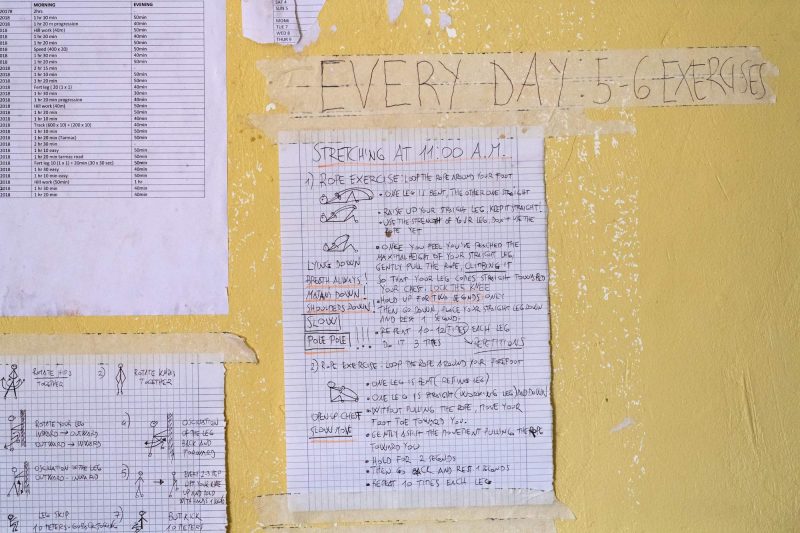

The runners' rigorous routines are important as well. The tape above a runner's exercise routine says, "Every Day." And that's part of it, too. It's a way of life.

A runner named Justin Kipchumba told The Guardian, he followed the same daily routine. "I sleep, I run, I eat. One day I will win big races,” he said. By 8 a.m. on the day of the interview he had already run 18 miles.

Source: The Guardian

One of the bonuses of the town is that there are few distractions stopping runners from training. Here, runners rest by playing pool.

Source: BBC

Food is another factor that's often pointed to. In particular a lack of junk food in runner's diets has been said to help the athletes.

Source: CNN

Renata Canova, a trainer who is called the "wizard," and who spends much of the year in Iten, told the Independent everyone was asking the wrong question. "We continue to speak about why the Kenyans are so strong. We should ask why is Europe so weak," he said.

Source: Independent

Put more gently, Brother O'Connell told BBC, "running is an extension of their lives. It's not something that's imposed on them - they do it instinctively."

Sources: BBC, The Guardian

Regardless of the exact reason for success, Rift Valley's reputation has grown, and dozens of running camps have sprouted up. Most are for Kenyans, but some are for overseas runners, too. Full time physiotherapists live in the area to keep the runners in good condition.

Source: France24

The Kenyan runners are hoping that by winning marathons or Olympic medals they can earn enough to secure their family's future, paying for children to go to school or buying farmland.

Source: The New York Times

But that hope isn't entirely realistic. According to The New York Times, while young runners continue training to give themselves and their families better lives, the reality is that very few actually can ever live off what they make running.

Source: The New York Times

Welsey Korir won the 2012 Boston Marathon. He's one of Kenya's top athletes and because of that the pressure's even worse for him. He's responsible for a foundation that pays for 300 children go to school, and which also supports 2,000 farmers.

Source: The Guardian

World champion runners like Korir, according to runner and writer Malcolm Gladwell, are idolized the way Americans idolize rock stars.

Source: The Atlantic

But they're also under a lot of pressure. Korir told The Guardian, “If I win a race, those kids go to school next year. If I don’t, they don’t. It’s a very big motivation. When you reach the pain, you have to have a reason."

Source: The Guardian

For those who do win big, the injection of money into their lives can have the same intoxicating effect as alcohol. Moses Tanui, who won the Boston Marathon twice, told The New York Times, “When you drink a lot of alcohol you become stupid — you don’t know what you’re doing. It’s the same when you get a lot of money.”

Source: The New York Times

For instance when Duncan Kibet won the Rotterdam Marathon in 2009 and ran the second fastest time ever at that point at 2:04:27, he won $180,000. But what was meant to be enough to set up his life was mostly gone within two years, after he helped pay for school fees for relatives, bought a house for his mother, and a car and clothes for himself.

Source: The New York Times

Kenya has also been plagued by concerns over athletes doping. Dick Pound, who investigated Russia for doping, said in 2015 it was, "pretty clear that Kenya have enjoyed huge success in the endurance events and it is also pretty clear that there is a lot of performance-enhancing drugs being used in Kenya."

Sources: The Guardian, Reuters

From 2004 to 2018, 138 Kenyans had tested positive for prohibited substances, but a World Anti-Doping Agency report said the incidents were uncoordinated, and not part of an institutionalized system.

Source: Reuters

But doping is a big concern for Kenya's runners. A ban from races means the runner has no way to provide. One Kenyan runner, who kept his identity secret, told Al Jazeera doping was a common practice, as his peers felt an intense pressure to succeed. "I know doping is bad, but as runners we have to support our families by whatever means. This is my livelihood," he said.

Sources: Al Jazeera

Drive, more than anything else, may be the reason why these runners keep on winning. As Korir told The Guardian, the reason they run so fast is simple. "We are running away from poverty," he said.

Source: The Guardian