- Researchers performed CT scans on a mummified Egyptian woman and found evidence of a second fetus.

- The fetus was in her chest cavity and seemed to be the twin of the fetus buried with the woman.

- Though women often die in childbirth, mummified fetuses are almost unheard of.

Finding a fetus in mummified remains is almost unheard of. Now scientists say they have evidence of a mummified teenager who died while delivering twins.

"This is the first mummy of its kind discovered," Francine Margolis, who led a study on the mummified remains, told LiveScience.

Aged between 14 and 17 years old, the teenager likely died in childbirth, more than 2,000 years ago. Embalmers had placed her wrapped fetus between her legs. It seems no one knew she was pregnant with twins.

For over 100 years, the remains were sitting in the Smithsonian Museum collection, until Margolis decided to take a closer look. She performed a CT scan on the mummified woman's remains to obtain pelvic measurements to confirm the cause of death.

But she discovered something surprising, instead.

There appeared to be objects in the chest cavity that didn't belong to the wrapped fetus.

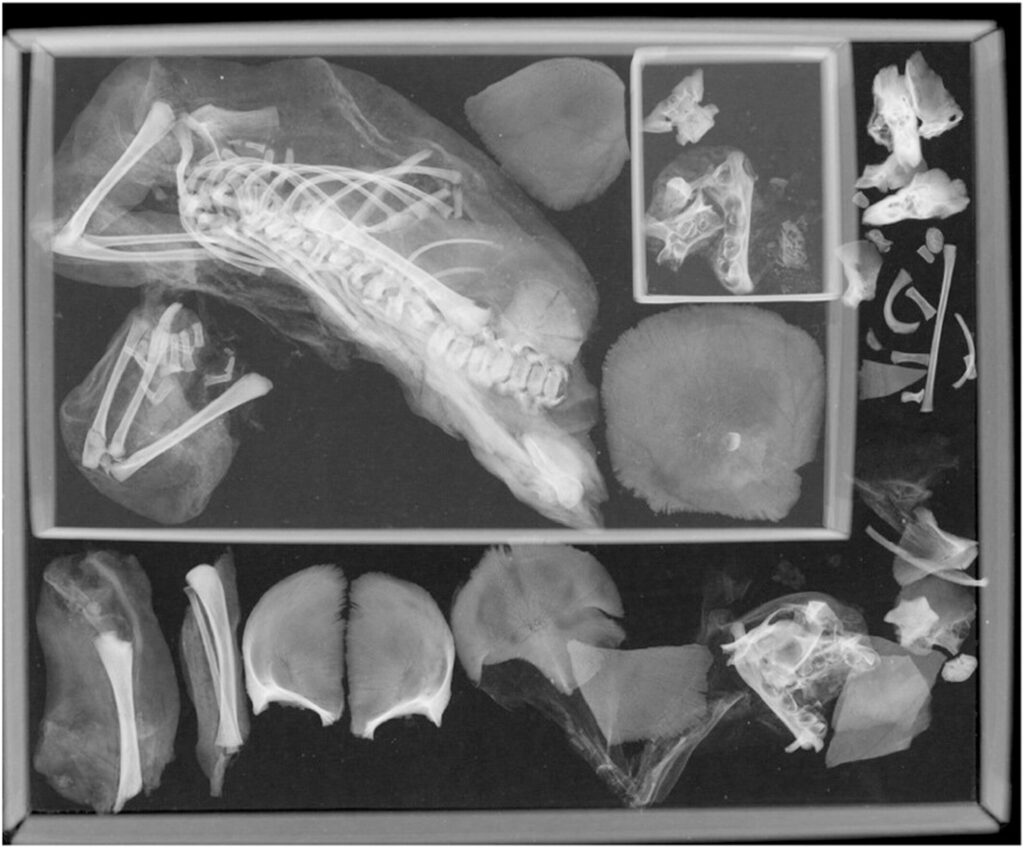

Margolis and George Washington University anthropologist David Hunt then examined X-rays of the remains and were surprised to see a second fetus, Margolis said.

"We both stared at the computer screen, at each other, and back to the screen," she told Business Insider in an email. She and Hunt published the finding in the peer-reviewed International Journal of Osteoarchaeology late last year.

An undiscovered twin

Researchers first excavated the mummy's remains in 1908. It's impossible to know whether the mother or anyone else knew about the second twin, Margolis said.

The second fetus' position inside the woman's chest cavity is also a mystery.

But researchers think the body moved to the chest cavity when the woman was embalmed. The process dissolved the diaphragm and connective tissues, allowing the fetus to migrate, they wrote in the paper.

Unsolved mysteries remain

Museum collections with human remains are controversial, and the Smithsonian no longer allows destructive tests using tissue, bone, teeth, or nail samples. Therefore, it's difficult to learn more beyond what CT and X-rays can reveal.

Moreover, the mother's head is missing, making it difficult to learn more about her overall health, Margolis said. One photo of the mummified mother's head exists, but after it was photographed, it may have been reburied, gone to a local museum, or been stolen, Margolis said.

CT scans are less invasive than other tests, and a new round could offer more insight into the mother and twins, Margolis said.

For example, the first fetus's head was inside the woman's birth canal. While Margolis and Hunt are sure this led to the mother's death, it's difficult to determine if the fetus' body was detached during embalming or as a result of traumatic fetal decapitation, when a baby's head detaches during delivery. CT scans focused on the fetus's skull could provide new information, Margolis said.

In 2022, researchers cast doubt on the only other known mummy of a pregnant woman. Scientists have theorized that the embalming process was unable to preserve evidence of pregnancy, making this new finding very rare.