- Ben Silbermann is the cofounder and CEO of Pinterest, the image sharing site.

- Pinterest will reportedly exceed $700 million in annual ad revenue and is valued at around $12 billion.

- Silbermann built a community around his company by hiring people based on their passions, and by personally meeting Pinterest’s earliest users.

- Silbermann is naturally a quiet person, and developed a meeting approach that kept the most outgoing employees from dominating the conversation.

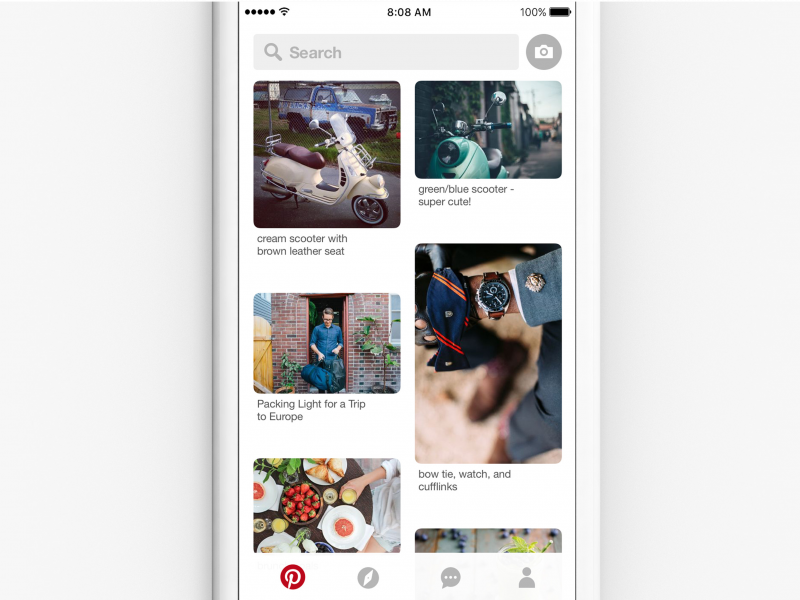

Ben Silbermann is the cofounder and CEO of Pinterest, the image search tool that lets users save and share their favorite photos, designs, and recipes.

Over the last eight years, Silbermann has quietly built Pinterest into a global brand with 250 million active users. And while the company is private and keeps financials to itself, CNBC reported in July that Pinterest may hit $1 billion in ad revenue this year, and in September the New York Times reported that number will be closer to $700 million, and that the company has a valuation of $12.3 billion.

Silbermann’s journey to Pinterest started when he was still working at Google in 2007, and his friend Paul Sciarra asked if he wanted to explore making software for the newly released iPhone.

Listen to the full episode here:

Subscribe to "This is Success" on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, or your favorite podcast app. Check out previous episodes with:

Transcript edited for clarity.

Ben Silbermann: We just started brainstorming. What are the different things we could do on the phone that would be different than what you could do on the computer? We made a game with some friends. It was a trivia game, so anybody could write trivia on any topic, and anybody around the world could play it. So I was always playing with that idea of what could you do with technology and with the internet that would be fun and useful for lots and lots of people.

Richard Feloni: And how did this first company pan out?

Silbermann: It wasn't that great. Paul and I decided that we wanted to help put catalogs on the phone. Everyone was getting catalogs in the mail, and it felt so archaic. You'd get this big stack of paper catalogs.

Feloni: Like retail catalogs?

Silbermann: Yeah. Just everyone's mailbox was full of them. And we thought, "What if you could put that on the phone?" Then you'd save a lot of paper, and you could only look at the stuff that you wanted to look at. So we set out to build that, but it was bad timing. This was right after the financial crisis. And we needed to put together a little bit of money to support ourselves and to build the technology. And it was just the worst time to raise money. I remember we would visit investors, and they would be telling us, "We're putting all of our money into gold. We're not investing in technology startups." So we spent a long time trying to put together that very first round. And I remember at some point we became pretty desperate, because all of the traditional routes had been closed to us.

So I started reading about these college business-plan competitions that you could enter that had a cash prize. And I found one. It was at NYU. And the rules were written pretty loosely. It said you didn't have to go to NYU; you just had to know somebody that was a student at NYU. And we ended up entering that contest. We got second place, and second place had no cash prize, but you got a meeting with a venture capitalist. And so at the meeting, the venture capitalist - I don't know; maybe because he took pity on us - said, "We'll do half of your round if you can put together the other half of the round." And so when he said that, we then called up all the other people that we'd ever spoken to. This was random people out of college, alumni directories, people that we'd read about in the newspaper that were wealthy. We said, "Hey, we talked to you before. A venture capitalist from New York is going to fund us. If you want in the round, get in there. It's going to close in a few days." And that's how we put together our first little bundle of money.

Feloni: So what did this experience teach you, ahead of Pinterest?

Silbermann: It sounds really cheesy: It just taught us that persistence pays. We didn't feel like we really had anything to lose. Actually, we literally didn't have anything to lose. So we didn't feel bad about asking people. But the other thing I learned was that investors - they kind of want to hear that you're selling the future. You're selling a dream of what could be. And when I used to go in and pitch investors, I was very careful not to over-promise what we could do. So I would say, "Hey, you know, we don't have any money. We don't have any experience doing this. But we think this is a good idea. We're going to build this piece of software." And I couldn't understand why they weren't funding us, but it was probably the worst sales pitch they'd ever heard. And I think I learned that people don't expect you to have all their answers, but they want to see that you have confidence that you're going to figure it out in the future. That's the same with investors. It's the same with the employees you hire. They want to know that you're going to work through those twists and turns, and try to figure out the solution even if you don't know the answer right then.

Discovering a project is the right one to pursue

Feloni: So at what point did you decide that Pinterest was going to be something that you would work on?

Silbermann: We'd been working on this smartphone app. And it wasn't really taking off. Back then, every single app had to be approved by the Apple App Store, and sometimes it would take weeks or months to build it. And at that time, I had also become friends with a guy named Evan Sharp, who was a student in New York. Evan and I, kind of cut from the same cloth, both of us -

Feloni: How did you meet him?

Silbermann: I met him through a mutual friend. Actually, a pretty loose connection. It was a guy that neither of us knew that well in college. And he said, "Hey, you guys both love the internet. I think you should catch up when you're visiting New York." I remember meeting Evan, and yeah, we just hit it off. We started talking about how much we enjoyed the internet, all these great things we wanted to build. And we had one idea that we both shared, and it was a product that we wanted for ourselves. We wanted to be able to take all the cool things we found on the internet and just collect them in one place, so you could access them later, and you could browse the collections of other people. I used to collect things as a kid. I collected bugs and stamps. Evan collected baseball cards. And then he was in graduate school, so he was also collecting a lot of visual imagery while he was studying architecture. And so we just started building that on the side. And that was how Pinterest came to be.

Feloni: At one point did it turn out to be that, "OK, you know what, this little project that we're working on, this is actually going to be what we need to dedicate ourselves to?"

Silbermann: Well, when we first built Pinterest, the first thing we noticed about it was that we personally just loved the product. So we were using it all the time. And there weren't a lot of other users. But we were able to keep iterating on it and making it better every single day. Whereas the phone app, we had this really long cycle between when we would make changes, and then submit it into the store, and then they would get approved over time. And so the natural momentum was with Pinterest, because we could work on it every day. And then slowly, we started sending it out to just our friends, our family. They started telling their friends about it. And pretty soon, people started telling us they really liked it. It wasn't a lot of people. But we would get notes from them and say, "Hey, I love this project." When it would go down, because sometimes it would go down, people would write to us and they would say, "Hey, Pinterest is down. I'm really depending on this to redecorate my home or to plan out my wedding." And so we decided to double down on Pinterest.

Feloni: And as you were building up this initial audience, who were these people?

Silbermann: A lot of them were folks like the people I grew up with. So a lot of people from the Midwest. I grew up in Iowa. A lot of people where Evan was from, in York, Pennsylvania. And they were using it not because they were tech early adopters. They weren't the kind of people that had the newest phone or downloaded everything. They were using it because it was really useful in their everyday life. And the most common way that people would hear about Pinterest, and the most common way they hear about it today, is somebody would do something. They would throw a party, or they'd redecorate their home, or they'd cook a special meal. And their friends would say, "Hey, where'd you get the idea?" And they'd say, "Oh, I got that idea on Pinterest." Then they'd say, "Oh, what's Pinterest?" And they'd try it out and download the app.

Feloni: So that word-of-mouth approach was something that you still use today?

Silbermann: Yeah. I mean, I wouldn't say that we use it as much, as it just happens.

Feloni: It just happens.

Silbermann: You know, we live in a time where everyone's carrying around these really sophisticated devices. And so you don't have to be a technology early adopter in order to hear about something and then try it just a few moments later.

How to build a community

Feloni: How did you build up a team around Pinterest?

Silbermann: Well, the first thing that we really looked for were people that started with what the product would do for a customer. They were extremely focused on how to make the experience of using it better, and then they worked backwards into the technology. And that turned out to be super important, especially in the early days when the team was just four or five people. Because the thing that kept us working really hard was we really wanted to make the folks that were using the product have an amazing experience. I remember I used to put my cellphone number on every outbound email. Because I wanted to make sure that if Pinterest wasn't working, you had somebody to call. And so I would get calls at all times of the night, all through the day.

Feloni: So every user would have your number?

Silbermann: Every user had my cellphone number. And you'd get calls from people that just wanted general technology support, like not even to do with Pinterest. They're like, "My computer's really slow." So eventually I had to get rid of that cellphone number because it was going off all the time. But it was more the ethos that every early user would feel like they were part of a special community, and we were really dedicated to giving them a great experience. So that was one thing that we looked for in all of our early employees.

Feloni: I mean, just starting out, you have a small team. And when you have those intimate relationships with your founders and the first team, was there something that you would ask, to be like, "All right. This person passes the test?" Was there a question or an insight that you could have?

Silbermann: I don't think we had a secret interview question. But we spent a lot of time as a team together. I mean, we were there every weekend, all night. We all knew each other's families. We'd go out to dinner with each other's kids. And so it really felt, in those very, very early days, like a club or a family of people, because we knew each other so well. In fact, the very first office was in an apartment, like a lot of companies. It was a two-bedroom apartment. There was actually another guy living in one of the bedrooms who wasn't working with the company. We all worked in the living room. Every Friday, we would have a barbecue because we had a grill. It was bring your own food. People from the neighborhood would come. We ended up actually recruiting a lot of people from those barbecues. They'd come three, or four, or five weeks in a row. They'd say, "It looks like all of you are having a really good time. We love the product. Let us know when you have any openings." That was the feel really early on at the company. Of course, as we grew in scale, you can't recruit hundreds of people through barbecues. That's not a long-term strategy, but I did think it set the right tone in those really early days.

I remember when we were recruiting early on. There were these people that were at great jobs, and I would almost feel guilty pulling them out of this great job. We didn't have a cool office. It was bring your own computer. There were going to take these massive salary cuts. I would almost feel guilty about saying you should leave this amazing at a Google or a Facebook and come work for us. What I realized was they're really great people, that challenge, all that constraint, the fact that you do need them to fulfill the mission, that is what's motivating. They're not looking for you to guarantee that everything is going to be the same. In fact, part of the reason they talking to you is they want a new challenge. If you just embrace that, if you don't try to cover up all of the company's warts and challenges and say, "Here are the big challenges we have. It's going to be risky, but it's going to be a big adventure." The best people will self-select into that. The wrong kind of people, people that they just want all of their perks poured into a smaller company, will self-select out. When I understood that, it made the price of recruiting feel extremely honest and extremely transparent and actually really fun because you're looking for that special breed of person that sees their career as an adventure and a chance to do something that has a lot impact, rather than just as a job to make money and to have something to do during the day.

Feloni: As far as your approach to your job, are you still able to speak with users of the company and get their ideas?

Silbermann: Yeah. Both Evan and I try to make a very deliberate effort to reach out to the community and spend time with users. Sometimes that means leaving the office. We'll go on trips to different cities around the world. The purpose isn't PR; it's just to meet people who are using the product, understand what's working, what's not working, what's annoying, and then bring that back to the team and try to set the example that everybody should have a very firsthand feeling for how to make the product better and for who's using the product. Obviously, everyone can't be out of the office visiting people all day so we have a lot of other tools as well. We have research teams that bring users in and publish reports inside the company. We obviously have a lot of data and analytics where we look at how people are using it objectively. The trick is to put all those things together and form a picture of what your customers are looking for and then prioritize the things that will have the biggest impact that you can execute really, really well.

How to become a leader

Feloni: In terms of being the CEO and the leader of the company, how did it feel when the company started to get a lot more attraction and public attention?

Silbermann: Well, honestly, it was a little bit surprising to us that this tool that we started to build for ourselves, and then was used by our friends, and then our friends of friends, could be something that was useful to so many people. That was a great feeling. We were incredibly excited. Right after that, we felt this huge sense of responsibility to make sure that we could scale the quality of that product out to more and more and more people. I remember, at some point, we had millions of users but the team was still only 12 or 13 people. I sat down with Evan and we both realized that we needed to make recruiting an amazing team core to what we do every day. We had been spending time with the product, very, very hands on. We realized that unless we invested in building a team around us of people that had different skills and different backgrounds, and could help scale this thing, the whole operation might collapse under its own popularity. I think that was an important turning point from just thinking about ours jobs as building a product to thinking about jobs as building a team, and a culture, and a group of people, that could, together, build a product that would fulfill a mission over time. That was a big light bulb for both of us that happened pretty early on.

Feloni: What do you follow on Pinterest?

Silbermann: Geez, all sorts of things. Some of it's really practical. I've got two little kids. They're 3 and 6. We're always looking for things to do on the weekend with them, activities to help them out in school, really easy recipes that don't take long to make that our kids will eat. Some of them are more about my hobbies. I love nature. I love photography. I love reading pretty eclectic articles and I use Pinterest to save all of those things. I have secret boards for Christmas gifts I'm planning to buy people, vacations that I want to take someday. It really runs the gamut.

Feloni: In some profiles of you they describe you as a quiet, humble guy. First of all, is that accurate?

Silbermann: I think maybe everyone else is loud! Yeah, I think, on average, I'm a little bit quiet.

Feloni: Was that ever a difficulty in terms of being the CEO of a scaling company when they're asking you to make public appearances or just even talking to an ever-growing crowd?

Silbermann: That's been a work in progress, for sure. We've always wanted for our product to speak for itself. That when people think of Pinterest, they don't first think of a face or a personality, they think of a product that helps them do something really fulfilling in their life. But at the same time, there's a reality to running a company, which is people want a spokesperson to explain what you stand for and what you do so that's been something every year I have to work on. I have a team and their whole job is to help me work on that. Hopefully, I'll get better at it, year on year.

Feloni: How do you think that your leadership style evolved as the company kept growing?

Silbermann: Well, there are some things that haven't changed. We've always tried to keep a very, very sharp focus on what are the needs of the user? Everything else should follow that. But in terms of how it's implemented, it's just different at 10 people, and then 20 people, and then 100 people. Today there are more than 1,000 people. I would say there are two differences. One is, very quickly you realize you can't do everything yourself, so you really have to empower all these great people to be able to lead their own teams. Really great people, they want direction, but they don't want to be told how to do their job. That balance between when you start controlling every pixel and letting go of that a little bit and letting people own large pieces is one transition. The second is communication. When we were really small, everyone was in one room. You don't have to think about communication or meetings. Everyone just knows what's going on because there's only a handful of you. As the company gets bigger, it becomes important to communicate across a bunch of different channels and actually to repeat the same things again and again because an individual in your company, that may be the only time they're going to interact with you in a week, or in a month. You need to keep repeating the same message to make sure that it's consistently heard across the whole company.

Feloni: When you're saying, in terms of things that you're working on as a leader, would it be on the communication front, both internally and externally?

Silbermann: That's certainly one thing. I have a whole list of self-improvement projects.

Feloni: Is it an actual list you have?

Silbermann: There's a list and then I have a pinboard, of course -

Feloni: Of course.

Silbermann: - of interesting things that I read about. But every CEO, and actually most professionals I know that are successful, are pretty focused on constantly getting better and improving in the areas where they see gaps. I don't think I'm an exception to that.

Feloni: How would you define the culture that you built around Pinterest?

Silbermann: I would say that the culture really values diversity of all forms. Diversity certainly of skillsets. We have people that went to college and people that didn't go to college. People that studied engineering and people that studied design. It's one thing to recruit people from lots of different backgrounds; it's another thing to create a culture where all of those different skillsets can actually be knit together and can work towards a common good. We try to create an environment where you don't have to be the loudest to make a decision. If you're not the best verbal communicator, you can communicate through design or through data.

Feloni: How do you mean? Through presentations?

Silbermann: Yeah. One thing I noticed when I was working at other companies is that there's almost this tyranny of articulate people. That if you're really [good] at making an argument in a group setting, you can run the place. But the problem is the skill of making an argument in a group setting isn't the same as the skill of building really great products for users. In fact, sometimes the reason that people are great engineers, are great designers, is precisely because that's the medium that they best express themselves. We try to create an environment where you can speak through the work that you do rather than always having to make a verbal argument or debate about why something should or shouldn't be the case.

Feloni: How do you balance that in meetings when you're saying, "Oh, someone could just be the loudest in the room, they'll get their idea heard"?

Silbermann: Well, it depends on the meeting. My favorite meetings are ones that start with a very clear understanding of what problem are we trying to solve for our users. I'm a visual person. It's not a coincidence that I confounded Pinterest. I love it when people show the work rather than tell. They show the prototype or they show the design. They explain this is how I would use it personally. I find those are ones where it's much easier to make a decision on which direction we should take.

Feloni: Even though Pinterest isn't in the same social sphere as Facebook or a Twitter, it's still an app that people incorporate into their daily lives. There're nonstop discussions around just privacy concerns or how is my data being collected. Pinterest, though, hasn't really ... I haven't seen scandals around that. How have you maintained that trust of a user base?

Silbermann: Well, we think privacy is incredibly important, and we think it's also very important to be clear with a consumer about what's going on. There are two kinds of boards. There are boards that anybody can look at and browse and there are boards that are secret. In that sense, I think it's quite simple service. The other thing about Pinterest that's really helpful for us is we make money through advertising. Unlike a lot of services where advertising is kind of bolted on, on Pinterest there is a very, very close alignment between what people are there to do, which is get ideas, and what the advertisers are there to help them do, which is to get ideas. That basic alignment is really important. If I'm using Pinterest to redecorate my home, I actually want advertisements from furniture providers or from a paint provider because I can use those to make my home better. That alignment, I think, makes a lot of the conversation and expectation setting with users a lot easier because people can see why there's an exchange in value between advertisers and Pinterest and between the users and the advertisers. That's something that's important for us to preserve over time.

Feloni: It's like a look into the transparency of it?

Silbermann: Well, it just sort of makes sense. Advertising online gets a bad rap because a lot of times you're very clearly there to do something other than see ads. I want to watch this TV program or I want to communicate with my friends. Ads don't actually make the experience better in any way. But on Pinterest, you're there to get ideas to go do things in your life and lot of those things are enabled by the products and services that businesses provide, and so there's a logical connection between why you're using Pinterest as a user and why you're seeing ads as a user. That alignment, it's good for users, it's good for us a business, and it's good for the people that use our advertising products.

Feloni: Pinterest is still private. Are you considering taking it public, and do you have an idea of what an advantage would be and what maybe a disadvantage would be of that?

Silbermann: Well, long term, we want Pinterest to be an independent company. We don't comment on when or if we're going to public, but we tried to build it all along the way to be a company that can be self-sustaining. Self- sustaining financially, self-sustaining culturally, and that's because we think that the mission that we're on to try to bring everyone inspiration. It's a big mission. It's not a small functionally mission. It's one that we could realistically pursue for 10 or 20 years and still have a lot of work to do. We've always had big ambitions for the company because the mission that we've chosen to undertake is one that has a long time horizon to fulfill.

Feloni: What would be next for the company in terms of fulfilling that long-term vision?

Silbermann: We're working on a bunch of stuff that I am extremely excited about. One area is, how do we give you better and better personalized inspiration? At a very broad level, we want to take the best of human curation, so this ability for somebody to pick out the 10, 15, 20 items that are meaningful to her, and we want to combine that with cutting-edge machine learning and recommendation, so every time you open Pinterest you're greeted with almost a catalog that looks like and feels like it was handpicked for you. Then once you get that inspiration, we want to make sure that you can make it part of your life. For us, that means that everything that you see we can connect it to a place that you can buy it your price point. If there's a recipe, we can make sure that it's a good recipe and it's going to turn out well. If you want to add how something turned out, you're empowered with publishing tools to add this is how this project turned out. Those two things, I think, for a long time are going to keep us busy, technologically, in terms of design and community building. But if you fulfill those, they'll have a really transformative effect on people's lives.

Sharing his best advice

Feloni: We've talked about the span of your career. What would you say is the biggest challenge that you've overcome?

Silbermann: Well, I think the biggest challenge I've overcome is being able to recruit people to come and work with me that have very, very different skillsets. I feel like that's one of those superpowers in anything you do in life, that you don't have to be good at everything, what you have to be good at is finding people who are better than you in some area and convincing them that by joining up, the two of you can do more together than either of you can do separately. That took me a while to get my head around, how to do that well, but I honestly think it's one of the most rewarding parts of building a team and building a company. It's that all of you can together do something that no one of you could accomplish by yourselves.

Feloni: How do you define success?

Silbermann: For me, success is about building products and services that are useful. I think now that I have little kids, I realize that by the time they're my age, everything in the world is going to be different. I just think about my parents. When I was born, there were no personal computers in most people's houses, there was no internet, there was certainly no services on top of that internet, or mobile phone. There are like multiple degrees of innovation away. But my parents, who are doctors, many generations later can still say I spent my time making people's lives better by removing cataracts. I think for me, success would be that even as technology changes, we can look back and say that the products and services we built brought people joy and were useful in their lives, even if the way that they do that may have changed over the passing of a bunch of years.

Feloni: Is there a piece of advice that you would give to someone who maybe wants to have a career like yours or draw inspiration from it?

Silbermann: Yeah. My advice would be try to surround yourself with really great people, and also everything can be learned. I think some people kind of count themselves out. They feel like it's too late to pick up a new skill or to learn something. But the reality is that if you set your mind to it, I really do believe that you can learn anything and you can improve and what you can't learn fast enough, you can find great people to help you do those things along the way.

Feloni: It's the balance there.

Silbermann: Yeah.

Feloni: Well, thank you so much, Ben.

Silbermann: Thank you for having me.