- Pacific Gas & Electric Co. power lines have caused more than 1,500 California wildfires in the past six years, including the deadliest blaze in the state’s history.

- Many critics, including Gov. Gavin Newsom, have accused PG&E of prioritizing profits over safety measures for decades.

- The company has filed for bankruptcy, and it recently started cutting power to millions of Californians to keep power lines from sparking in dry, windy conditions.

- Many Californians think they should never have been faced with the choice between multiday blackouts and deadly fires.

- Here’s what experts say PG&E should have done years ago, from better tree trimming to power-line upgrades.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Over the past week, the Kincade Fire has torn through nearly 78,000 acres of California wine country, forcing about 180,000 people to evacuate. At the same time, millions have gone without electricity, often for days at a time.

Hospitals scrambled to find refrigerators for medications, people bundled their children to keep them warm during cool nights, and seniors were left alone in the dark.

The state’s largest utility, Pacific Gas & Electric Co., is responsible for these blackouts and possibly for the fire itself.

About the same time the Kincade Fire ignited, a jumper cable broke on a PG&E transmission tower in the area, the company told state regulators on October 24. By the time PG&E personnel arrived, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, known as Cal Fire, had taped the area off and identified the broken cable.

A problem with PG&E equipment was also the cause of the Camp Fire, a California state agency said, which killed at least 85 people last year and razed more than 18,800 structures. It was the deadliest and most destructive fire in California history.

In fact, according to The Wall Street Journal, the utility company's equipment led to more than 1,500 fires from June 2014 to December 2017.

So this fall, as low humidity and strong winds created fire-hazard conditions in northern California, PG&E cut power to nearly 1.1 million customers in October to minimize risks that sparking wires could start more blazes.

PG&E CEO Bill Johnson said Californians should expect these types of preemptive service interruptions for another 10 years.

"We recognize the hardship of not having electric service," a PG&E representative told Business Insider in an email. "While we recognize that the scope of these events is unsustainable in the long term, it was the correct decision given the large-scale, historic weather events and ensuing equipment damage that unfolded across our service area."

But many Californians say they should have never been forced into this choice: deadly fires or multiday blackouts. Instead, PG&E's critics accuse the company of shirking safety precautions to funnel money toward investor dividends.

The Los Angeles Times columnist Michael Hiltzik suggested PG&E might now be "the most detested, and detestable, corporation in California, if not in the observable solar system."

Here's how the company wound up in this position, and what it could have done instead.

Prioritizing 'the bottom line over everything'

After a PG&E pipeline exploded in 2010, killing eight people, state regulators started investigating the company. They found that PG&E had collected $224 million more than it was authorized to collect in oil and gas revenue in the decade before the explosion. At the same time, it spent millions less than it was supposed to on maintenance and generally fell short of industry safety standards.

"There was very much a focus on the bottom line over everything: 'What are the earnings we can report this quarter?'" Mike Florio, who was a California utilities commissioner from 2011 to 2016, told The New York Times. "And things really got squeezed on the maintenance side."

A 2017 report to state regulators highlighted PG&E's lack of a comprehensive safety strategy, unclear communication about safety between management and field personnel, and tendency to take action only after a major disaster.

Anticipating the cost of billions of dollars in legal claims associated with the Camp Fire and other fires from 2017 and 2018, PG&E filed for bankruptcy in January.

"We should not have to be here - years and years of greed, years and years of mismanagement, particularly with the largest investor-owned utility in the state of California, PG&E," Gov. Gavin Newsom, one of the company's most vocal critics, said in a press conference about the Kincade Fire on October 26. "We will do everything in our power to restructure PG&E so it is a completely different entity when they get out of bankruptcy by June 30th of next year."

Randy Harris, who owns a gift shop in Santa Rosa that lost customers during the blackouts, told The Washington Post that he shared Newsom's opinion of the utility company.

"I think they've been supporting their shareholders and executives more than they've been looking out for the public," Harris said.

PG&E needs to trim trees

Engineers and energy experts are quick to note a long list of safety practices PG&E should have prioritized.

For one, the company should have been more actively trimming dry trees, many say. Vegetation can ignite when it rubs against high-voltage wires - the kind that sit at the top of the large power lines that run between cities - because those wires aren't usually covered in insulation. (Low-voltage lines that connect to homes are generally insulated.)

"The utilities have tried to do a good job, but they have had a great deal of difficulty in doing safe trimming of their trees," Otto Lynch, the CEO of Power Line Systems, an electric-utility software developer, told Business Insider. (Lynch did not comment on PG&E's practices specifically.)

"If we could just keep the trees away from the wires, we wouldn't have to worry about it," he added.

In February, PG&E released a $1.6 billion wildfire-safety plan in which it set goals to clear branches that hang over power lines, identify trees that could fall onto the lines, and more than double the number of trees it trimmed in 2019.

As of September 21, however, the company had trimmed less than a third of those trees - just 760 miles of the 2,455 miles of power lines it had pledged to clear. PG&E cited a lack of personnel as the reason for the slow progress, according to the San Francisco Chronicle.

After its first round of blackouts in early October, PG&E discovered more than 100 problems with its power lines. Most of the affected equipment had been inspected in 2018 or 2019, according to the San Francisco Chronicle. If electricity had been flowing through those lines, the company told a judge, there were 56 issues - like fallen trees and wind-toppled poles - that could have lit California's bone-dry shrubbery on fire.

Of those incidents, 44 were caused by vegetation.

PG&E identified another 156 incidents of damage during more power shutoffs at the end of October.

Better, newer equipment could make the grid more resilient

The transmission tower that caused the Camp Fire was about 25 years too old by PG&E's own standards, but the utility had not made any moves to replace it in the years leading up to the fire, a New York Times investigation found.

The company's safety plan also set goals about replacing aging hardware and upgrading infrastructure. Such upgrades include covering high-voltage wires with insulation to prevent sparks of molten metal from erupting when wires touch branches or slap together in high winds.

Another simple hardware upgrade mentioned involves replacing wooden poles with sturdier, less flammable ones made from materials like steel or concrete.

As of August 31, PG&E said it had installed fire-resistant poles and covered power lines on 75 miles of its grid in fire-prone areas. It plans to complete 150 miles of these installations by the end of 2019 and 7,100 miles over the next 10 years.

The company also plans to replace old equipment with Cal Fire-certified alternatives and install transformers that contain fire-resistant fluid. (Transformers help move electrical currents from high-voltage to low-voltage wires, and the electrical activity inside them is a frequent wildfire culprit. One fire this week in the Bay Area may have been sparked by a PG&E transformer.)

PG&E's plan also mentions long-term aspirations to move wires underground in particularly fire-prone areas. For a bankrupt company, though, that's tough: For the price of burying 1 mile of power lines, $3 million, PG&E could build almost 4 miles of new overhead lines, according to the company's estimates.

Even good equipment needs to be monitored

Experts often point to a different California utility as an example of the right approach: San Diego Gas & Electric, which implemented many of the changes PG&E has been slow to accomplish after a lawsuit accused it of causing a destructive 2007 wildfire.

SDGE also broke up its grid into smaller segments so it could shut power off only in isolated areas with the highest fire risk.

Of course, even a fully upgraded, vegetation-cleared power line can occasionally collide with a dry branch, especially amid powerful winds. The Getty Fire in Los Angeles this week was sparked when strong wind caused a broken branch to land across two high-voltage wires.

That's why San Diego Gas & Electric's efforts didn't stop with just clearing trees and fixing equipment.

The company has also made monitoring its system a priority. It collects data on every pole and transmission tower in its grid, monitors weather conditions for fire risk at 177 stations, and records video with 100 high-definition cameras across its network, according to The New York Times.

The company says it has spent $1.5 billion on upgrading, maintaining, and monitoring its power lines since 2007.

"You're proactive about monitoring the health of an asset. You don't run it to failure," Shawn Chandler, the director of IT at the Pacific Northwest utility PacifiCorp, told Business Insider. "The low-hanging fruit in this system, to use a catch phrase, is always with analytics, a smart grid, line sensors, good vegetation management programs, frequent line inspections."

PG&E's grid extends over a much larger area than SDGE's. But the company plans to follow San Diego's example and install 600 high-definition cameras by 2022, followed by 1,300 weather stations in the next five years.

As of mid-September, PG&E had installed 94 of those cameras and a 600 weather stations.

As climate change increases wildfire risk, Californians could be stuck between blackouts and deadly fires more often

Though PG&E has begun implementing new safety measures, the company is also facing the effects of a warming climate, which causes vegetation to get drier and lengthens the wildfire season.

A 2016 study found that 75% more forest dried out in the western US from 2000 to 2015. Over that time period, western states gained nine extra days of high fire potential a year, on average.

Overall, the research showed, climate change nearly doubled the amount of forest that burned between 1984 and 2015, adding over 10 billion additional acres of burned area. In California in particular, the annual area burned in summer wildfires increased fivefold from 1972 to 2018.

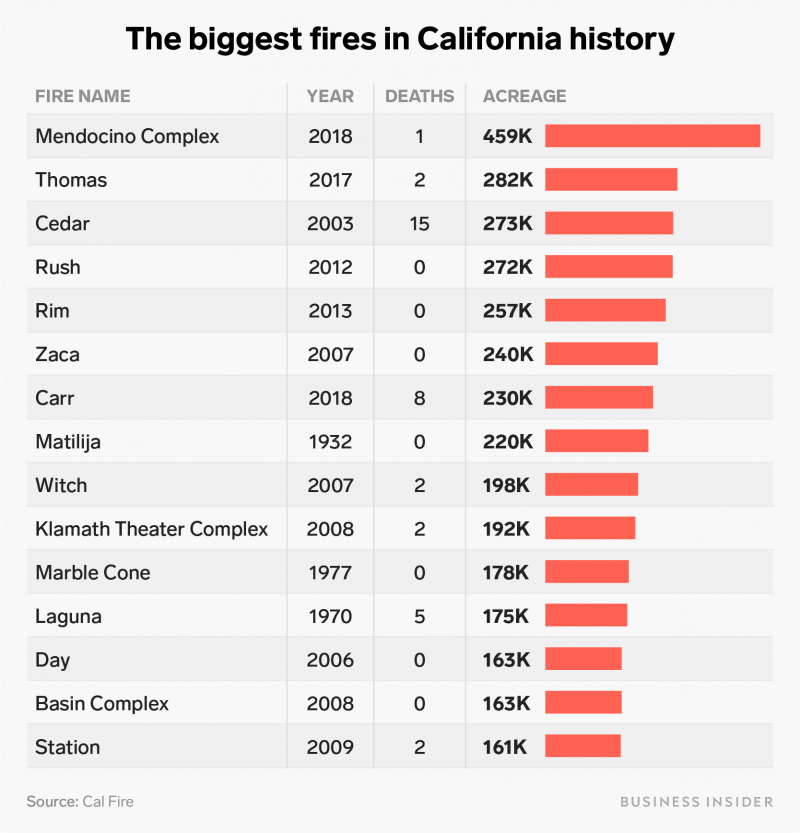

Nine of the 10 biggest fires in California history have occurred since 2003.

So when power lines do spark, these climate conditions mean drier vegetation is more likely to ignite. Then the resulting fires are more likely to grow than they were 20 years ago.

As the world continues to warm, wildfires are expected to keep get bigger and more frequent.

Johnson, PG&E's CEO, has indicated that blackouts will probably continue to be the company's go-to strategy when risk is high.

"We'll likely have to make this kind of decision again in the future," he said at a news conference on October 10.

In the three weeks since that statement, the company has cut power four times.