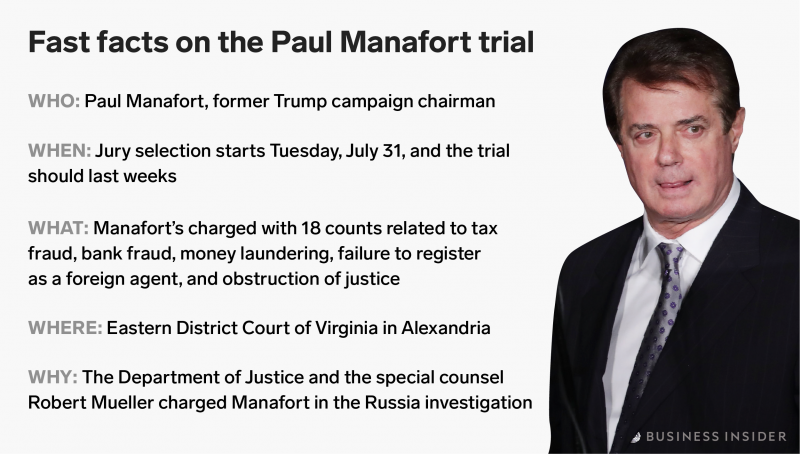

- Paul Manafort, the former chairman of President Donald Trump’s campaign, is going on trial in the first court case to come out of the special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation.

- Jury selection begins Tuesday, then the trial is expected to last weeks after that.

- Here’s what you need to know about what to expect, the prosecution’s roadmap, the defense’s rebuttal, and Manafort’s high stakes gamble.

Sign up for the latest Russia investigation updates here »

The former chairman of President Donald Trump’s campaign will be the first to face trial Tuesday as part of the special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election.

Paul Manafort stands charged with 18 counts related to tax fraud, bank fraud, money laundering, failure to register as a foreign agent, and obstruction of justice.

The indictment, brought by the Department of Justice (DOJ) in the Eastern District of Virginia, says Manafort committed many of those crimes while working as an unregistered lobbyist in the US for the Ukrainian government and pro-Russia interests beginning in 2006.

Rick Gates, Manafort's longtime business partner and the former deputy chairman of the Trump campaign, was initially named as a co-defendant with Manafort, but he struck a plea deal with prosecutors in February.

Gates pleaded guilty to two counts related to conspiracy and lying to the FBI. He will testify on behalf of the prosecution in the Manafort trial.

What to expect

Jury selection begins on Tuesday.

The process kicked off last month when prosecutors submitted a lengthy questionnaire to screen potential jurors for any biases.

Prosecutors say they expect to be finished presenting their case to the jury in eight to 10 days.

The trial is expected to last a total of three to four weeks, which experts say is fairly typical for a fraud case like Manafort's.

US District Judge T.S. Ellis III, who is overseeing the trial, has repeatedly instructed the parties to leave politics out of it. He reminded potential jurors to do the same last week.

Alex Whiting, a former federal prosecutor in Boston and Washington, DC, said there are two things at play that protect a jury from being tainted by bias, political or otherwise.

The first is the screening process, known as voir dire.

The second thing, he said, is that there is a "culture and atmosphere created in the trial process and in the courtroom" that reminds jurors of the "importance of a fair trial, the stakes, and the consequences for a defendant if they don't put aside their biases."

Ellis indicated as much to the potential jury pool last week. He reminded them that their work was a critical facet of the US legal system, and that they had to judge Manafort solely based on the evidence presented at his trial.

"Nothing you do as an American citizen is more important," Ellis said. "Together with voting, it is one of the two cardinal duties of being an American citizen."

The prosecution's roadmap: Rely on the facts and outline Manafort's extravagant spending

On Friday, prosecutors released a list of potential witnesses they may call on to testify during the trial.

The list, which included Gates, has 35 names, many of whom are Manafort's former business associates.

The list also included purveyors of luxury goods, like a high-end men's clothing dealer, a Mercedes Benz salesman, and a ticket vendor for the New York Yankees.

Their inclusion indicates that prosecutors will spend at least some time highlighting Manafort's extravagant spending over the last decade.

"Prosecutors love to throw in all the over-the-top spending fraudsters usually go for, and Manafort is no exception," said Jeffrey Cramer, a longtime former federal prosecutor who spent 12 years at the DOJ. "First of all, it's relevant because you're following the money. Second, it has a lot of jury appeal."

Whiting said that based on the indictment against Manafort, the government appears to have a strong case.

The document is a "speaking indictment," a term lawyers use to describe a charging document that is lengthy, detailed, and includes more information than is required by law.

Whiting said that while the case will include a little political context based on the nature of the charges, for the most part, it's a run-of-the-mill fraud case.

Cramer agreed.

"There's nothing special about Paul Manafort, other than that he was in close proximity to the president of the United States," he said. "The facts of this case have nothing to do with politics or Russian collusion or Trump. It's just a guy who was acting as a lobbyist when he shouldn't have been, collecting money for those efforts, and trying to hide that money away. That's what prosecutors will focus on."

The defense faces an 'uphill battle' unless they use politics to their advantage

The defense, meanwhile, "has an uphill battle" based on the indictment and other court filings the prosecution has made, Whiting said.

Joshua Dressler, a law professor at Ohio State University, told Reuters that although the evidence against Manafort seems strong, he lucked out by drawing a favorable judge like Ellis.

A Reagan appointee, Ellis is known to be tough on prosecutors, and he demonstrated as much during several pre-trial hearings in the Manafort case this year.

Dressler added that as much as the judge may try to keep bias out of the trial, the political climate surrounding the case increases the chances of a hung jury that can't reach a verdict.

Cramer echoed that point and said it was exactly why it would benefit Manafort for his legal team to weave more political subtext into the proceedings.

"If they fight this battle on just the facts, it's a tough case," he said. "If you're a defense lawyer, you want to talk about anything other than the facts here. So if you can taint the investigation as political in nature or a witch hunt, especially now, your hope is that it'll resonate with at least one juror and get your client off the hook."

Manafort's defense until now rested largely on two pillars: arguing that the case should be tossed out because the crimes he was charged with are irrelevant since they have nothing to do with Russian collusion, and arguing that the scope of Mueller's mandate was too broad.

Ellis rejected a motion last month from Manafort's lawyers to dismiss the Virginia case on both of those grounds.

Manafort's gamble: Could Trump pardon him?

That said, the biggest question for legal experts isn't the dynamic of the case, but why Manafort chose to go to trial in the first place.

The answer to why Manafort hasn't flipped, they say, can likely be boiled down to one thing: a presidential pardon.

Rudy Giuliani, Trump's lead defense lawyer, said the president is not currently considering pardons for anyone caught in Mueller's crosshairs.

Giuliani said Trump wants to wait until the Russia investigation is over, at which point he may grant pardons to those he believes have been treated unfairly.

"Manafort maximizes his chances of getting a pardon by going to trial," Whiting said. "In his situation, given the facts of his case, the rational thing to do is plead guilty without cooperating and get the benefit of a guilty plea, or plead guilty and cooperate and get a bigger benefit. The only way it makes sense for him to go to trial is if he thinks he's going to get a pardon."

The New York Times reported in March that John Dowd, Trump's former lead defense attorney, floated the possibility of pardons to both Manafort and former national security adviser Michael Flynn last year, as the Russia probe was closing in on both men.

Whiting said that if such an offer was made - which Dowd denied - it could explain Manafort's willingness to face trial.

He added that this outcome is also the most beneficial to the president.

"If Trump pardons Manafort now, then Manafort can be subpoenaed to testify," he said. "And of course, if Manafort pleaded guilty, he may choose to cooperate. The pardon dangle encourages Manafort to hang tough, not cooperate, and reap the benefit later, maybe in a year or two."

But Cramer said there's an important caveat in Manafort's case.

"He's banking entirely on the whim of the president," he said. "So it's a high stakes game of poker that Manafort's playing here."

One intriguing possibility that hasn't been explored as much is whether Manafort could flip after being convicted.

If he chooses that route, the former Trump campaign chairman wouldn't benefit as much as he would have if he had agreed to cooperate before going to trial.

"Unlike other defendants - and this is where politics come into it - Manafort is uniquely positioned to know things about other facets of the Mueller probe that have to do with the Trump campaign, and that's why he's valuable," Cramer said. "Would he talk about things other than what he's convicted for, about the president or anything else he knows?"