Summary List Placement

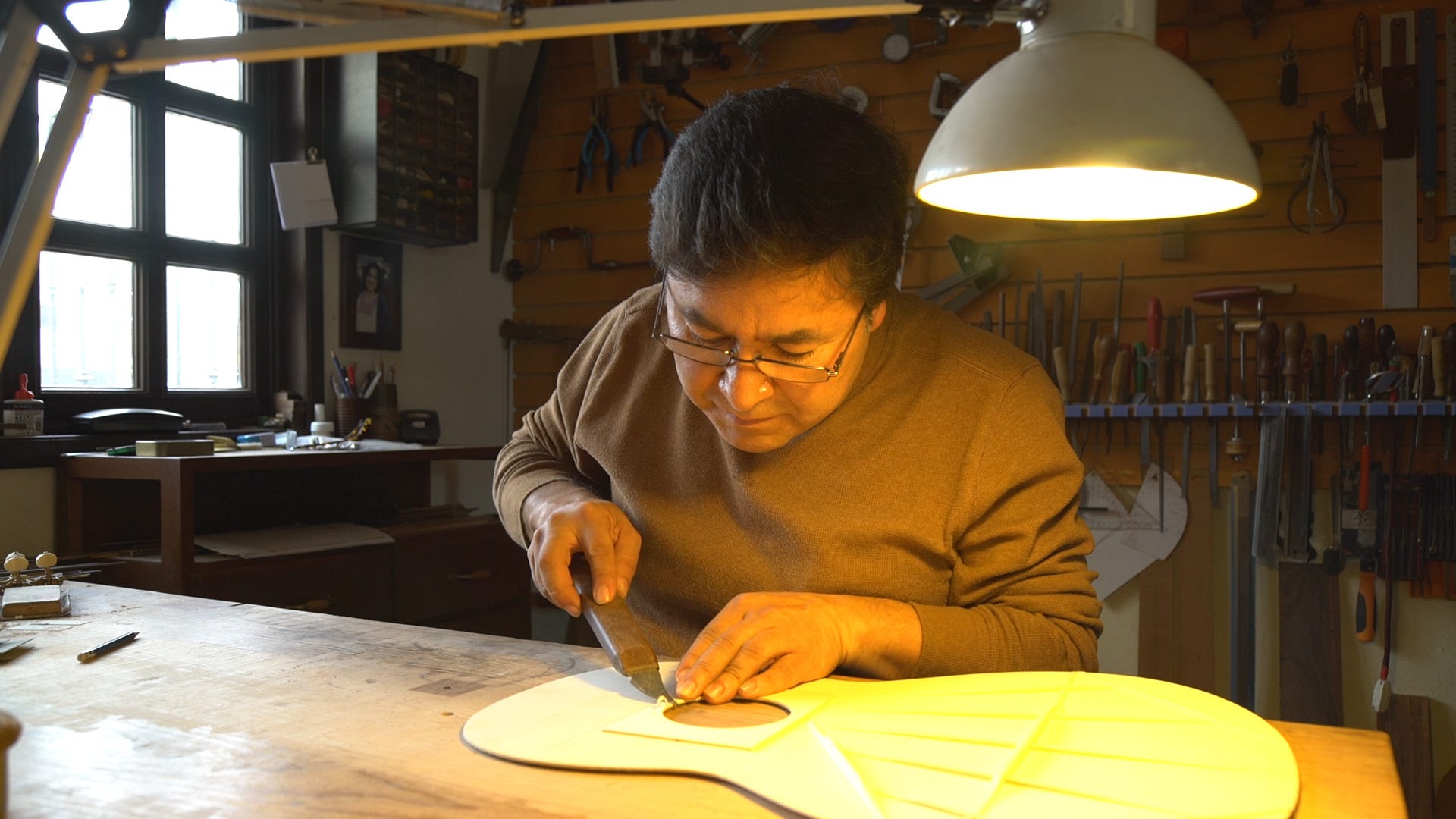

Making every piece of a guitar by hand is a rare art form.

That’s why the wait list to get one of Abel García López’s custom guitars is two years long.

The native of Paracho, Mexico, is one of the few guitar builders hand-making the entire instrument on his own.

"I believe that guitar makers like myself are an endangered species," López told Business Insider Today.

Making and selling guitars and accessories is the main source of income for most people in the small town of Paracho, about 200 miles west of Mexico City. It's been a guitar-building hub for centuries, but has attracted more attention recently thanks to the Pixar movie "Coco," which features a guitar designed by a Paracho native.

Not many guitar-makers master all parts of the building process - marquetry, fret-making, varnishing - like López. He comes from generations of guitar players and grew up helping out at his parents' shop.

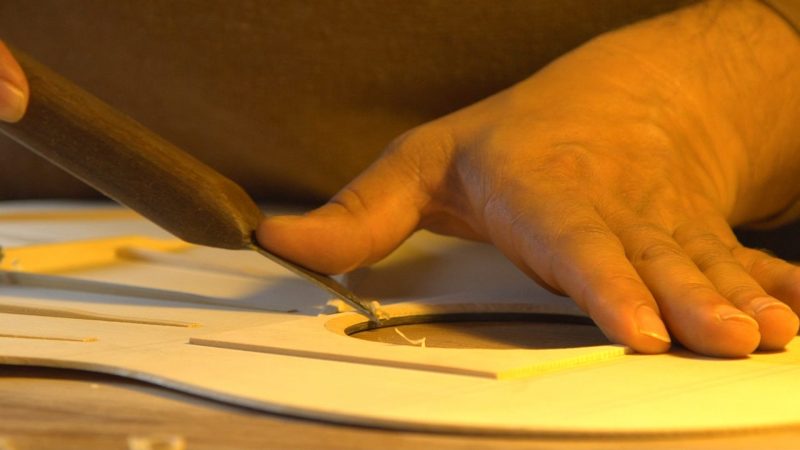

The building process begins with choosing the right type of wood. López typically works with palo santo wood from Brazil or tropical woods grown in Mexico.

"Conceiving a guitar is very interesting to me," López told Business Insider Today, "I start thinking of what I want to obtain from the moment that I select the wood. I'm already thinking about the sound I want to achieve. I think there are woods classified for certain sounds."

He takes his time sawing, sanding, carving, and assembling all the wooden pieces to construct a high-quality acoustic instrument.

The finishing touch is painting on a shiny varnish - a job that's typically done by women.

But in Paracho, job opportunities for women are limited. That's why Paracho native Hilda Jasso, the owner of a guitar shop in Mexico City, left her hometown to find work.

"In Paracho I wouldn't have progressed or taken my children where they are now," Hilda told Business Insider Today. "There we work out of necessity, because your work is not valued there. Here is where it is valued. And here, you can make a little more."

Hilda was always interested in becoming a "laudera," but she says that in a more traditional town like Paracho, she was expected to take care of the house rather than work.

Now, she repairs guitars in her Mexico City shop using a variety of skills - "how to put a graft on the lid, how to glue the head, put it on the palm, scrape, put flakes, make bones and varnish. I know everything," she said. And she knows how to spot a quality instrument - she's had to turn customers away who come in looking to have their cheap, mass-produced guitars repaired.

"I am honest with them," Hilda told Business Insider Today. "I tell them, 'Look, these guitars are fake, like Kleenex. Use it, and throw it away.'"

While mass-produced guitars might be more commonly used, López isn't worried about the competition - he sees his guitars as works of art.

"Guitar making, the way we work, is not a business to make money. And I am more interested in making artistic rather than commercial guitars."

His guitars range anywhere from $5,500 to $40,000. His most valuable piece took him 10 years to perfect.

But in the end, the biggest reward for López is satisfying the customer.

"Every guitar maker lives for these moments," he said. "You don't necessarily have to see it on a big stage or being played by such an important guitarist. It's more about watching someone play it with satisfaction, while the audience enjoys it too."