- There are 18 captive orcas in the US. They all live at SeaWorld parks.

- SeaWorld has stopped its orca breeding program.

- Animal activists and SeaWorld don't agree on what's best for the remaining 18 killer whales.

Orcas are large, highly intelligent, social mammals who routinely travel great distances in the ocean — on average about 40 miles a day. Because of their size and their need to swim far and dive deep, many scientists who study orcas argue that it's inhumane to keep them in captivity.

"The goal is to improve the welfare of the animals," Naomi Rose, marine mammal scientist for the Animal Welfare Institute, told Insider. "And being in a natural habitat is always going to be better for these animals than being in a concrete box."

Rose points to years of research showing the consequences of captivity, including hyperaggression, dorsal fin collapse in male orcas, repetitive patterns, like swimming in circles and regurgitating food, and severe tooth damage from chewing on concrete tanks and steel bars. Captive orcas can also show signs of chronic stress.

Public pressure to release captive orcas has grown in recent years, yet at least 54 remain in captivity around the world — 18 in the US at SeaWorld parks.

SeaWorld announced in 2016 that it would end its orca breeding program due in part to the backlash it received following the 2013 documentary "Blackfish."

The orcas currently in the company's care will be the last generation of killer whales at the park. Activists are advocating for their release.

But the question of where and how to release them continues to fuel debate about what's best for these killer whales.

The problem with releasing captive orcas into the wild

Orcas raised in captivity are likely to struggle if released into the open ocean, Monika Wieland Shields, co-founder and director of the Orca Behavior Institute, told Insider.

"Captive orcas may have a hard time adapting to catching wild prey as they never received training from their families," Shields said. "And hunting tactics are unique to orcas in every different population."

Many orcas raised in captivity also have health problems that could require ongoing human care and treatment. Those born and raised in captivity or who have been in captivity for decades are also at risk of coming into contact with infectious diseases their immune systems aren't prepared for, Chris Dold, chief zoological officer at SeaWorld, told Insider.

"We know wild whales and dolphins carry certain viruses and bacterial infections that our whales and dolphins have never ever been exposed to," Dold said. "And so their immune systems would presumably not be developed in such a way that they could fight that disease off."

The history of releasing captive orcas in the US

Only one captive orca in the US has ever been released back into the ocean — Keiko, the orca who starred in the 1993 film "Free Willy."

Efforts to rehabilitate Keiko began shortly after the film's huge success, and in 1996 he was transferred from a tank in Mexico City to a rehabilitation facility in Oregon.

There, Keiko was placed in a pool filled with ocean water and introduced to live fish for hunting. His health improved, and he gained 1,900 pounds in 18 months.

In 1998, he was transferred to a sea pen — a large part of the ocean marked off for rehabilitated marine animals to live — in Iceland where he continued to receive medical care from human caretakers.

Keiko first stayed in his sea pen as he acclimated to life in the ocean, but eventually was able to swim in the open ocean with the help of human guide boats. In the summer of 2002, he traveled 1,000 miles to the coast of Norway.

Keiko had many encounters with wild orcas but struggled to fully integrate with them. In 2003, five years after his release, Keiko died of pneumonia at the age of 27. Wild male orcas typically live about 35 to 50 years.

Because Keiko wasn't able to integrate with wild orcas, critics of the effort describe his release as a failure. But animal rights activists say Keiko was able to regain his health after years in captivity, and while his death was premature, he had years of freedom in the ocean.

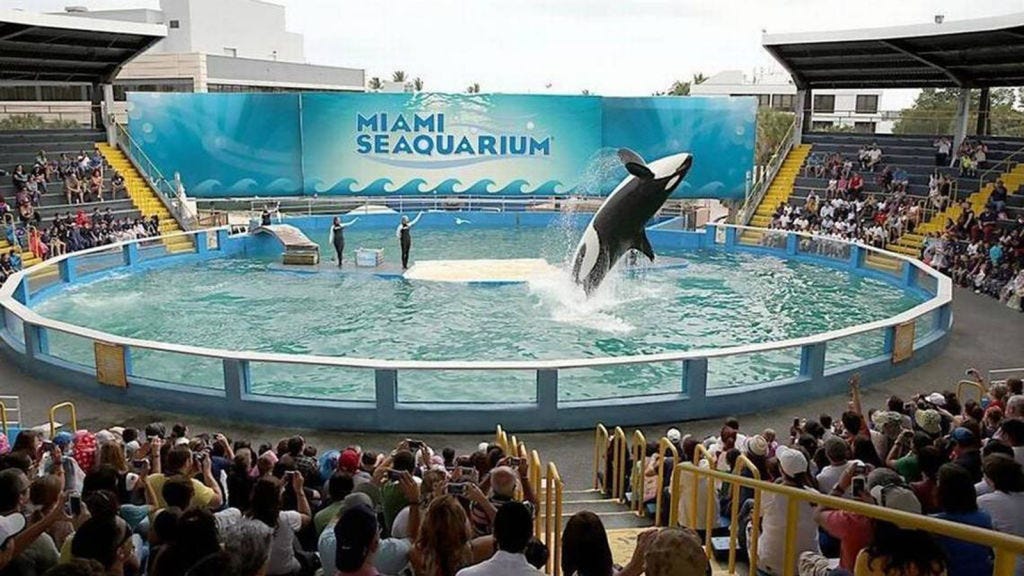

Similar plans were in place to release the captive orca Lolita, also known as Tokitae or Toki, who had been at the Miami Seaquarium for 50 years. But she died from complications of a suspected renal condition on August 18, 2023, before she could be moved to a sea pen in her native waters off the coast of Washington state.

Whale sanctuaries can help rehabilitate captive orcas

Keiko's story is why orca experts and animal rights activists support the creation of whale sanctuaries or sea pens.

In this setting, orcas can swim free but remain close to humans who can help provide food and medical care.

Sanctuaries exist for other animals that have been released from captivity, like elephants, tigers, and bears. It's harder to establish these kinds of rehabilitation spaces for large ocean creatures, like killer whales, but it can be done.

The sea pen in Iceland where Keiko was released now houses two beluga whales and could potentially hold other marine mammals, including killer whales, Mark Palmer, associate director of the International Marine Mammal Project, told Insider. There are also several warm-water marine mammal sanctuaries being built in the Caribbean and Mediterranean, Palmer said.

Lori Marino, founder and president of the Whale Sanctuary Project, is part of an effort to build the first-of-its-kind killer whale sanctuary in Nova Scotia.

Once completed, the sanctuary would occupy 100 acres of water space — big enough to fit about 75 standard American football fields. Depths in the sanctuary could reach up to 59 feet, which would allow orcas to swim farther and dive deeper than they can in marine park tanks.

For example, SeaWorld orca tanks average approximately 86 feet by 51 feet with a depth of 34 feet, according to PETA. SeaWorld didn't respond to Insider's request to confirm these measurements.

The WSP is working to secure final funding with plans to complete the sanctuary in 2024, Palmer said. The sanctuary would also include underwater cameras and hydrophones for members of the public to learn about and observe the orcas from a distance.

"The next step is to take these 18 remaining orcas in the US and bring them somewhere they can live out the rest of their lives in a more natural, healthy environment," Marino said. "It's a way to give back what was taken from them."

The future of orca captivity

Marino and other animal rights activists have urged SeaWorld to partner with them in efforts to build whale sanctuaries, but say so far the company has resisted.

"It would be unconscionable to risk the health and wellbeing of killer whales at SeaWorld by moving them to a sea pen, especially when killer whales at SeaWorld are living a healthy life in a safe and sound habitat where every need is attended to," SeaWorld told Insider in an email statement.

Animal rights activists say specifics about the health status of the orcas at SeaWorld are hard to come by as not much of that information is made public. But Dold said the orcas routinely undergo wellness checks that include taking blood samples, running diagnostic tests, and ultrasound imaging that show they're "thriving under SeaWorld's care."

Dold also cited concerns about potential hurricanes, oil spills, infectious diseases, and disruption of the ocean ecosystem if the orcas at SeaWorld are moved to a sanctuary.

Marino said the WSP has worked to address these concerns in a few key ways, including a three-year environmental assessment, which found that allowing whales into the region would not harm the ecosystem. The WSP also chose the location in Nova Scotia specifically because of its protection from storm surges during hurricanes. And the team plans to include facilities for the whales to go to in the case of an oil spill.

In terms of disease, Marino explained the team would conduct a full workup of the orcas' health and immune systems before transferring them. The whales would also have access to veterinary care at the sanctuary.

Another factor to consider in this debate is what the public stands to lose if the orcas leave SeaWorld. The opportunity for people to see orcas up close and for scientists to study and learn about them has led to a greater appreciation of these animals, Dold said.

Captive orcas have no doubt played a crucial role in expanding human knowledge, Shields said. For example, by studying captive orcas, scientists have been able to learn about orca gestation and metabolism — subjects that are much more difficult to research in free-ranging whales.

But Shields said this isn't a reason to continue keeping these animals in captivity.

"With that increased understanding has also come increased respect and an awareness of just how much orcas suffer in a captive environment," Shields said. "It's time to do right by these whales and give them the best retirement we can offer them and ultimately cease having orcas in captivity altogether."