SAN FRANCISCO – It’s finally in the water.

For five years now, The Ocean Cleanup, an organization founded by a 24-year-old Dutch innovator named Boyan Slat, has been trying to create a system that can clean plastic out of the world’s oceans.

There’s a mind-boggling amount of plastic in the oceans, and that amount grows every day. At least 8 million metric tons of plastic pour into the sea every year – a number that’s considered a low estimate, since it doesn’t include commonly found debris like fishing nets. As this trash breaks down into tinier and tinier bits, much of it is eventually carried into one of five massive ocean regions, where plastic can be so concentrated that areas have garnered names like the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

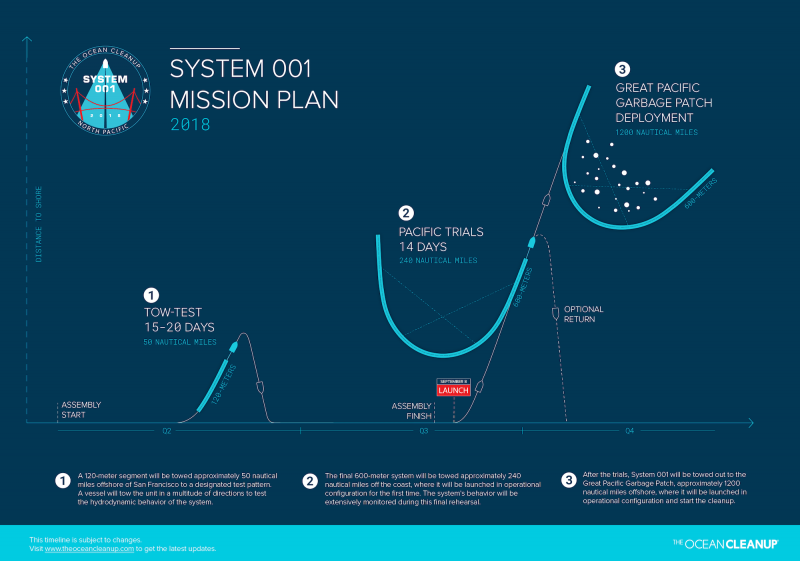

On Saturday, Slat’s organization began the journey out to sea with its first official 2,000-foot-long plastic cleaning array, System 001. A ship called the Maersk Launcher towed the device through the San Francisco Bay out under the Golden Gate Bridge, en route to a final testing site. If everything goes well, it’ll head to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, where the cleanup crew hopes the first system will be able to collect 50 tons of plastic in its first year.

Slat and colleagues hope The Ocean Cleanup's plastic-collecting arrays can help at least remove large debris from these swirling vortexes. They say their models show that with a full deployment of 60 arrays, they could be able to remove half of the garbage-patch region's plastic within five years.

But so far, their technology is still unproven, and no one knows for sure whether it'll work as planned.

The Ocean Cleanup's plan is an inspiration for many, an effort meant to confront what seems like an impossibly large and ugly problem.

But it's also received significant criticism from members of the scientific community who study plastics. Those researchers say the system may not be effective since it can't reach most ocean plastic that has started to break into tiny pieces and sink into the water. They fear it could have negative impacts on marine wildlife or could be broken up by harsh ocean conditions, or that it could be a distraction from stopping the overall use of plastic and the management that keeps it out of the ocean in the first place.

Slat says that stopping plastic pollution needs to be a global priority but that his organization believes cleaning up what's out there already must be done as well. Yet he knows the world and the scientific community are watching as the system begins its first real test.

"It's still not proven technology, and in the next months it has to do what it has to do," he told Business Insider. The group has run models and simulations and has tested systems in the water, but this is the first time a full-size array will be assembled and, The Ocean Cleanup hopes, functioning in the Pacific.

As he said Saturday, "models are models" - helpful but imperfect demonstrations of reality.

"It'll be an exciting six months," Slat said.

Here's what the initial deployment looked like.

The system was assembled in Alameda, California, in a shipyard in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Hard-walled pipe makes up the floating component of the cleanup array.

The Ocean Cleanup says the floating array is equipped with lanterns, radar reflectors, navigational signals, GPS, and anti-collision beacons.

Solar panels help provide power to these systems.

Below the floating part of the array, an impenetrable 10-foot skirt is supposed to help gather floating debris.

Earlier this year, the Ocean Cleanup built a 400-foot test array to see how it held up while being towed out into the water.

That trial unit was towed out to sea on May 18.

It survived the two-week tow test.

The full array is 2,000 feet long.

Designing the first full-size array cost about $23 million, though the team estimates that future arrays will cost under $6 million to make.

The first array will be towed 240 to 300 miles offshore, which should take about three days.

The device right now is long and straight, so there's not too much drag on it in the water.

But upon reaching the test site, it'll be assembled into its U-shape for approximately a two-week testing period.

Slat says that there, they want to see if the system keeps its shape and structural integrity once it's fully assembled — and they also want to see how it moves in the water.

If all goes well, it'll be pulled another 1,000 nautical miles out to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

Once the array is out there, the team plans to have a ship scoop up collected plastic approximately every six weeks.

But since this is a first array, the Ocean Cleanup expects they'll have to tweak and potentially redesign aspects of the cleanup arrays and the plastic collection process.

Once it reaches the garbage patch region, the team wants to see how efficient it as at capturing plastic.

Once winter arrives, they'll be able to see if it can stand up to massive waves and storms.

The first array might be complete, but its test is just beginning.