144 years ago today, for the first time in its history, the New York Stock Exchange shut down in response to a panic.

The 10-day closure followed the failure of Jay Cooke & Company Bank, which was unable to sell enough railroad bonds to meet other obligations.

In his latest market commentary note, legendary NYSE floor trader and director of floor operations for UBS Art Cashin outlined this fascinating moment in history.

Below is an excerpt:

“[O]n Saturday, September 20, 1873, for the first time in its history, the NYSE closed in response to a panic. (The word circuit breaker had not been invented yet….er…..neither had circuits.)

A week or more before, one of the most renowned firms in American finance and especially U.S. Treasury auctions came under a cloud of suspicion. The firm was Jay Cooke & Company. And, on most continents, it was seen as a key player. After all, its aggressive style had made it the key underwriter for the billions of Treasury bonds issued during and after the Civil War. (Contemporary competitors had shied back fearing that deficit spending had gotten out of control.)

Anyway, the concern about in this key brokerage firm only confused the market at first. But as this day approached, there were hints that the problems would spread to other brokers. On the 18th, liquidation of equities showed up at the 'first call.'

For most of its first century of existence, the NYSE was a 'call market.' The chairman, or other senior officer, would call out the name of one of the listed issues. Brokers who had an interest in that 'issue' would arise from their 'seats' and begin to bargain with any other brokers arisen from their 'seats'. When transactions ended in that issue (assuming they were not all buyers), brokers returned to their 'seats' and the chairman called the next issue on the roll. When the last issue was called, the session officially ended. There were two sessions each day. [...]

So, here they were. Rumors surfaced that, perhaps some other brokers were involved and the first call on the 18th turned soft. The second call turned soggy. Prices were down and with no on-going after market; all you could do (as the banks did) is await the next call.

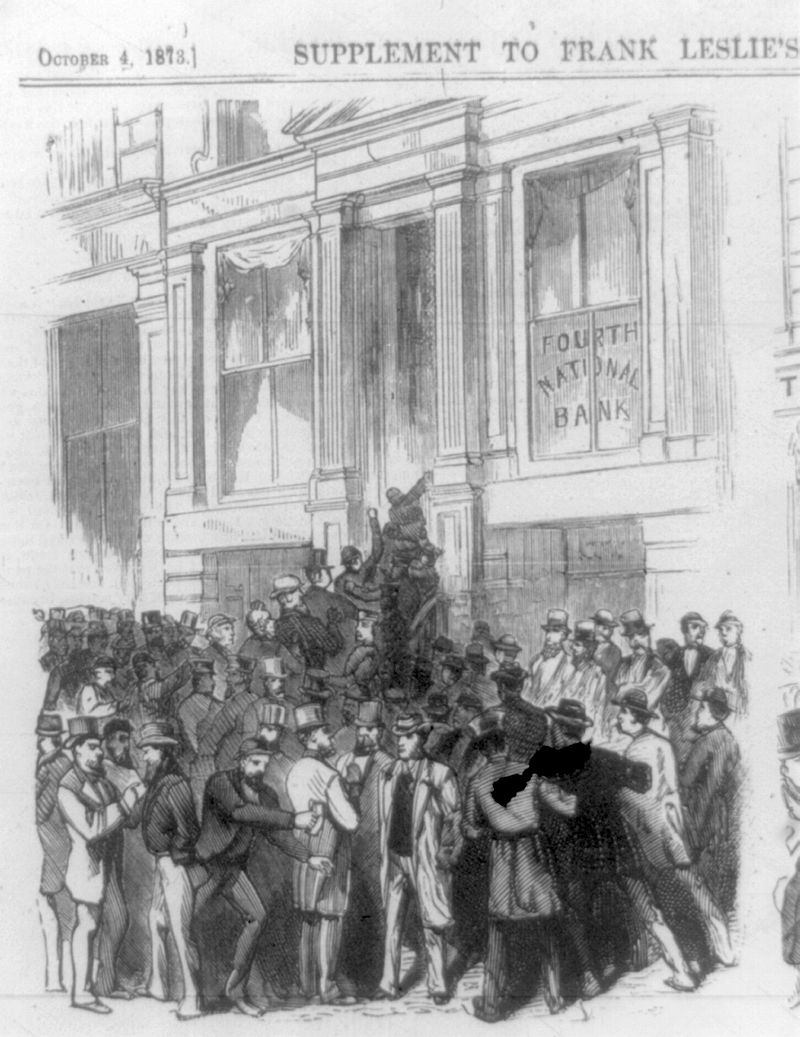

The morning call on the 19th was messy and the afternoon call was just a disaster. Outside, in a heavy rain, crowds gathered on Wall Street to withdraw securities and money from brokers. By the morning of the 20th anyone who was in the phone book (if there had been one at the time) was rumored to have been impacted by the problem.

So, naturally the morning call on Saturday the 20th was a disaster. So much so that the Exchange opted to close until the crisis calmed (skipping the P.M. call).

Close they did and for a lot more than one 'call.' But, but perhaps because banks and investors naturally needed some means of evaluating holdings, they reopened about ten days later. However, the rumors would not go away and liquidations and defaults continued. The history books call it the Panic of 1873. And, it put the American economy in a tailspin for years. (Nearly 10,000 businesses failed.)"