- The UN recently passed multiple rounds of sanctions designed to cripple the North Korean economy. It hopes the pressure will force the country to curb its nuclear programme. But experts say this hasn’t worked, partly because North Korea is propped up by a secret trade economy. Obama adviser on sanctions tells Business Insider it may be impossible to sanction North Korea into compliance without offering something in return.

Over the past six weeks, the United Nations Security Council has passed two fresh rounds of sanctions in an attempt to curb North Korea’s nuclear programme.

The first, in August, threatened to cut the country’s export revenue by a third. A second one in September banned its exports of textiles and capped imports of crude oil into the isolated nation.

In response Kim Jong Un threatened “thousands-fold” revenge and “the greatest pain and suffering” on the United States, which drafted the sanctions.

And North Korea has shown no signs of dampening its nuclear ambitions. Three days after the second round of UN sanctions, the country fired another missile toward Japan.

In fact, experts say sanctions might never succeed in isolating the North Korean economy from the rest of the world and ridding the country of nuclear weapons. Here's why.

1. North Korea has a secret economy under the radar of international monitors

North Korea has been under various economic restrictions for decades, and is pretty used to dealing with them, according to Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein, an associate scholar at the Foreign Policy Research Institute and co-editor of North Korean Economy Watch.

He told Business Insider: "Because it's been under various forms of sanctions for many years, the regime has been forced to use channels and methods outside of official frameworks, making the North Korean government very savvy when it comes to acquiring the goods that it needs."

A major strand of this strategy is a web of overseas shell companies and brokers, according to somebody with inside knowledge of the top levels of North Korean government.

Ri Jong Ho worked as a senior official at Office 39, a secretive cabal that operates slush funds for the country's leaders, before he defected in 2014.

"North Korea has procured Russia-produced fuel from Singapore brokers and others since the 1990s," Ri told Japan's Kyodo newspaper in June.

According to Ri, Office 39 also used names of Chinese and Russian contacts to open bank accounts to access international markets on several occasions.

The country also uses agents who buy goods for them, posing either as individuals or private companies, according to Katzeff Silberstein. They can then funnel them to the state without international monitors knowing, he said.

A recent investigation by US research group C4ADS claimed to find an example of this - Dandong Hongxiang Industrial Development (DHID), a Chinese company.

DHID has been sanctioned by the US and China for allegedly supporting North Korea's nuclear programme, and C4ADS said it had traded on behalf of North Korea via 43 business entities across four continents.

Between 2009 and 2015, DHID moved up to $75 million across the US alone while obscuring itself as companies based in regions including England, Wales, Hong Kong, the Seychelles, and the British Virgin Islands, according to US Justice Department documents.

C4ADS said: "Using loopholes and countermeasures, North Korea has been able to insert itself into border trade firms that act as proxies and enter the commercial system undisturbed."

Pyongyang has also been accused using fake identity and documentation for ships, which complicates authorities' ability to work out whether the ship has a connection to North Korea.

Marshall Billingslea, the US Treasury Department's assistant secretary for terrorist financing, accused North Korea of such behaviour in front of the US House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Committee last week.

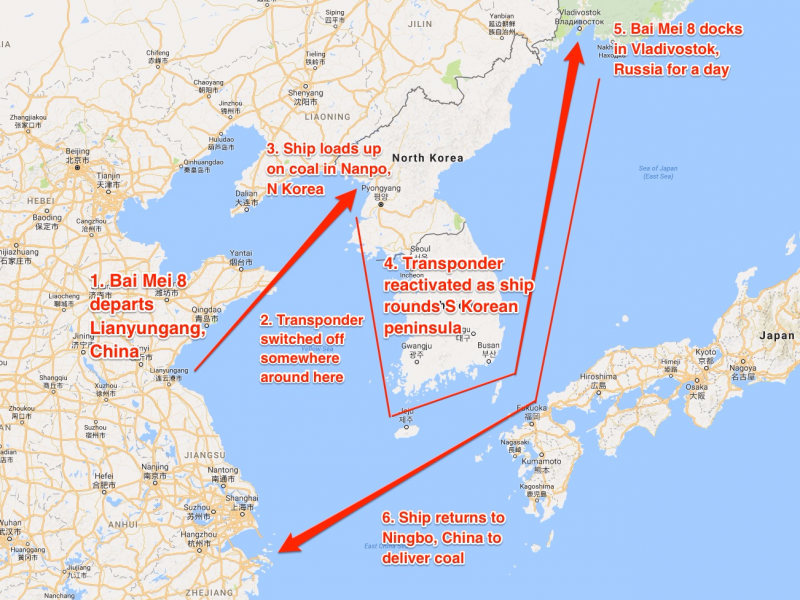

He also claimed that some ships switch off their locator devices while making covert visits to North Korea.

He described vessels which set sail from China, turn off their transponders as they head toward North Korea, load up on commodities such as coal, and then switch the devices back on as they rounded the South Korean peninsula toward Russia.

The ships would then dock at a Russian port, wait there a while, and then deliver the goods to a Chinese port, effectively enabling banned trade between North Korea and China.

By switching off their transponders - which is a violation of international maritime law - ships made their deliveries appears like they were from Russia, Billingslea said.

The graphic below shows the apparent trade route of the Bai Mei 8, a ship departing China under a Saint Kitts and Nevis flag, which declared to be going to Russia but in fact travelled to North Korea to Russia and back to China this summer:

North Korea has also been able to generate hard currency over the years by operating a sophisticated web of overseas smuggling and hacking, C4ADS reported.

These include the sale of military equipment, drug trafficking and rhino horns, printing counterfeit currency, and cybercrime, the research group said.

In the past two months alone, North Korean agents have been caught hacking bitcoin exchanges, and UN independent experts are investigating reports that North Korea attempted to sell weapons to Syria.

2. When one supply of smuggled goods is cut off, North Korea will 'just try to get it from somewhere else'

As China began to limit its fuel imports to North Korea this year, Russian smugglers appeared to fill the void by ramping up their trade with Pyongyang, the Washington Post recently reported.

Trade between Russia and North Korea rose sharply this spring, US officials told the newspaper, with shipments including goods that North Korea couldn't produce itself. These actions were "quietly [undercutting] sanctions intended to stop" Pyongyang's nuclear programme, the newspaper noted in its headline.

"As the Chinese cut off oil and gas, we're seeing them turn to Russia," an anonymous senior official said. "Whenever they are cut off from their primary supplier, they just try to get it from somewhere else."

Katzeff Silberstein, the foreign policy analyst, said: "The point with North Korea's mastery of avoiding official channels for their economic activities is not that sanctions don't make life difficult for many, many North Koreans and for the economy as a whole."

"Rather, it means that the impact of sanctions will probably never be as strong as policymakers would hope, and that completely shutting the North Korean economy off from the world is very difficult to do."

3. The country is used to shortages

While China's suspension of exports like petrol and diesel, in accordance with sanction rules, have already led to scarcity and price increases in the country, North Korea may remain undeterred because it's already used to shortages.

Chun Yung Woo, a former South Korean envoy, told Reuters: "North Koreans are so used to living in harsh economic conditions that they would just get by for at least one year even if the oil ban is adopted, rationing the existing stockpile among top elites at a minimum level and replacing cars, tractors, equipment with cow wagons, human labour etc."

"They would also manage to produce oil from whatever resources are available, whether it be coal, trees or plants," he said.

4. North Korea is hell-bent on developing its nuclear programme

North Korea is prepared for war with the US, and possesses multiple nuclear missiles and underground bunkers, according to Evan Osnos, a New Yorker writer who visited the country this summer.

"Today, we've got everything we need in our hands," Osnos recorded Jo Chol Su, a senior diplomat, as saying, "and it's preposterous to think that new sanctions and new threats will change anything."

Andrei Lankov, the director of NK News and a professor at Seoul's Kookmin University, also said that no amount of sanctions, negotiations, or UN resolutions will curb Kim Jong Un's nuclear ambitions.

"I don't think these talks [at this week's UN General Assembly] are going to bring any results, because North Korea's position is quite clear: They want to be capable of obliterating the city of New York and the city of Washington, DC, a number of times," Lankov told CNN.

Only until Pyongyang is certain it can strike the US continent, then they "might be willing to start talking about" scaling down its threats, although it remains too early to tell, Lankov said.

Richard Nephew, a former Obama adviser and a senior research scholar at Columbia University's Center on Global Energy Policy, told Business Insider that there are inherent limits to the sanctions regime.

He said that while UN sanctions cannot be held directly accountable for North Korea's ongoing nuclear development, the fact that North Korea has continued its nuclear and missile tests anyway suggests that sanctions have not effectively contained Pyongyang's ambitions.

It may even be possible that increased sanctions and international criticism are encouraging Pyongyang's nuclear ambitions, Nephew said.

Jeffrey Lewis, the director of the East Asia Nonproliferation Program at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies, echoed this view.

With its neighbours effectively ganging up to force North Korea to disarm, "the last thing you would do in that situation is give up your independent nuclear capability," Lewis told The New York Times in September. "[It's] the one thing you hold that they have no control over. You would never give that up in that situation."

If the goal is "true denuclearisation" - the removal of all nuclear weapons - in North Korea, "the US will be trying for a million years," Nephew said.

So what will work?

The UN should make clear what actions it wants from North Korea with every round of sanctions passed, instead of automatically expecting deescalation, said Nephew, who served as the Obama administration's lead sanctions expert during its Iran nuclear deal negotiations.

"Sanctions will always fail if you don't prioritise the objective and don't understand the degree [to which they] materially affect decisions," he told BI, adding that it's pointless to continuously impose sanctions "just because it's something to do."

38 North Contributor @RichardMNephew on proposed UNSC sanctions against #NorthKorea pic.twitter.com/ZzEz6d3HzO

— 38 North (@38NorthNK) September 11, 2017

Instead, world leaders should focus on getting North Korea to peaceful negotiations and extend viable incentives to North Korea to deweaponise, as the US did with Iran, Nephew said.

Trump previously ruled out negotiating with North Korea - a strategy which was contradicted by his Defense Secretary James Mattis. He also attacked another deal designed to dampen nuclear ambitions, Obama's controversial pact with Iran, which he called "an embarrassment" in a speech to the UN on Tuesday.

C4ADS, on the other hand, advocated freezing the assets of North Korean shell companies, such as Dandong Hongxiang. The US Treasury Department recently froze the assets of 18 Chinese and Russian entities for their links with North Korea, and has threatened to continue doing so.

"By targeting action against these host companies, as the US and China did in the case of DHID in September, 2016, the international community is doing more than simply freezing the assets of a single host," the report said. "They are preventing the regime from accessing the global financial system."

But this may be easier said than done, Katzeff Silberstein said: "The point is that [North Korea] is very difficult to monitor and more so to sanction. It's not impossible but it's hard.

"The North Korean regime has had so many years of practice in these routines and have adapted their whole system to the need to often use illicit channels to evade international regulations and sanctions regimes.

"Ironically, its weakness makes the North Korean more resilient than many might think."