NASA/Joel Kowsky

- Seven countries signed on to NASA’s new Artemis Accords on Tuesday: Australia, Canada, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, the United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom.

- The Artemis Accords establish basic rules for exploring the moon, Mars, asteroids, and comets — rules like: be peaceful, help astronauts in distress, share scientific data, and mine space resources sustainably.

- China and Russia are not on board yet. NASA seems to be courting Russia, but is legally prohibited from working with China.

- NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said that more countries were “anxious” to sign on, possibly by the end of 2020.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

NASA is preparing to build a permanent base on the moon and, eventually, send astronauts to Mars — a feat it can’t accomplish alone.

The agency gained seven allies for future deep-space exploration on Tuesday, when the US signed a new agreement with Australia, Canada, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, the United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom.

The Artemis Accords, named for NASA’s moon-and-Mars-bound human-spaceflight program, lay out some general rules for nations to follow as they join the effort: be peaceful, work together, and don’t leave behind junk that will cause problems for future space missions.

NASA

“This is the beginning of, I think, what is going to be an amazing opportunity to explore the moon and go on to Mars with the broadest, most diverse coalition in the history of humankind,” NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine told reporters in a briefing on the announcement.

“We’re establishing what the rules and the norms of behavior are as we do this, so that we can preserve space and make sure that when we do explore, we’re doing it with peaceful purposes, we’re doing it with transparency and clarity to avoid any kind of misperceptions and any kind of conflict.”

The Artemis program, as NASA has laid out in a $28 billion proposal, would launch an uncrewed mission around the moon in 2021, followed by a crewed moon flyby in 2023, then a lunar landing in 2024.

Then NASA plans to build a permanent moon-orbiting base called the Gateway, similar to the International Space Station that orbits Earth. From there, the agency hopes to build a base on the lunar surface, where it can mine the resources required to fly the first astronauts to Mars.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

All of this will require international and commercial partners.

With the Artemis Accords, NASA hopes to ensure that none of these partners ruin space for everyone else. The agreement builds on the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, translating its ideas into the new era of space exploration.

"If you want to join the Artemis journey, nations must abide by the Outer Space Treaty and other norms of behavior that will lead to a more peaceful, safe, and prosperous future in space exploration — not just for NASA and its partners, but for all of humanity to enjoy," Mike Gold, acting associate administrator for NASA's Office of International and Interagency Relations, said in the briefing.

Bridenstine promised the accords would onboard new countries in the near future. But for now, two major spacefaring nations — China and Russia — are notably absent from this new coalition.

Principles for deep-space exploration

The new accords detail 10 main principles which signatories agree to follow:

- Peace. Cooperative activities under the Artemis Accords should be "exclusively for peaceful purposes."

- Transparency. Participating nations should share their policies and plans for space exploration, as well as any scientific information they obtain from activities under the accords.

- Interoperability. Space-based infrastructure should be designed so that everybody can integrate their technology to fit it — like an "iPhone for space," where anybody can design an app or hardware that easily plugs in, Bridenstine said.

- Emergency assistance. Participating nations agree to help astronauts in distress.

- Registration of space objects. New spacecraft under the accords should be registered

- Release of scientific data. Participating nations should share scientific data obtained during activities under the accords with the public and the international scientific community.

- Preserving outer space heritage. Participants should preserve historically significant landing sites, spacecraft, and other artifacts.

- Space resources. Participants should extract and use space resources (like water on the moon or minerals on asteroids) safely and sustainably. Further, mining on a celestial body (like the moon) does not mean you own that body.

- Deconfliction of space activities. Participants should avoid harming or interfering with each other's use of outer space, and they should establish "safety zones" for activities that could be harmful.

- Orbital debris. Participants should avoid creating new debris in orbit by disposing of defunct spacecraft and avoiding collisions or spacecraft otherwise breaking apart.

The document is available in full on NASA's website.

Though private companies will not sign onto the Artemis Accords, Bridenstine said, they will be beholden to the agreement if their governments sign on.

"There's a lot of pressure that can be brought to bear on countries that choose to be part of the Artemis program, but then don't play by the rules," Bridenstine said. "I guess ultimately they could be asked to leave the Artemis program, but I would hope that they would come to a better resolution than that before it gets that far."

China is prohibited, and Russia is holding back

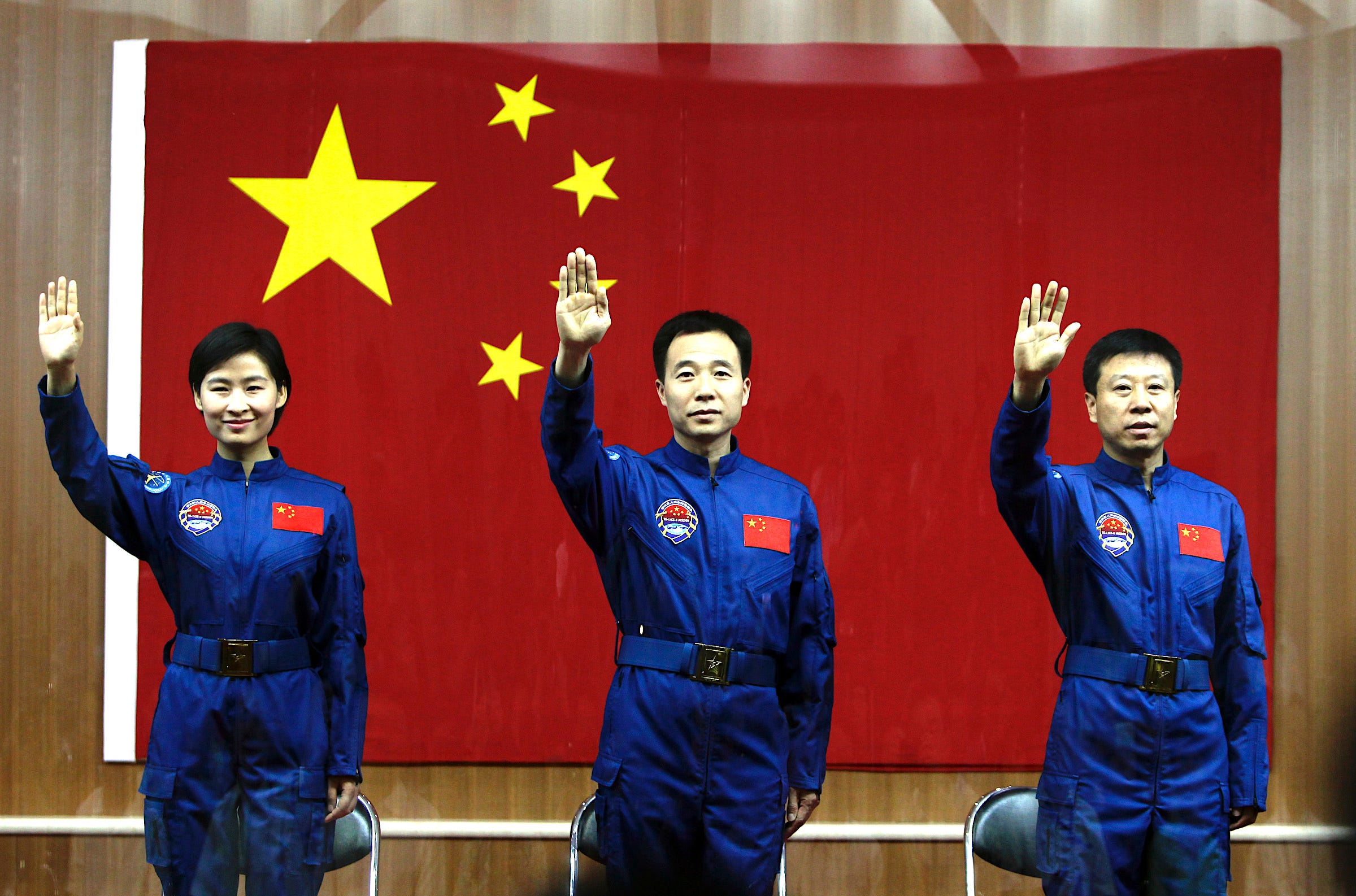

Jason Lee/Reuters

NASA is proceeding, at least for now, without China and Russia — home to two of the world's most robust space programs.

China's absence was a given. NASA has been unable to collaborate or coordinate with China ever since Congress banned the agency from doing so in 2011.

In Russia's case, it's less clear.

Roscosmos Director General Dmitry Rogozin described NASA's moon-base plans as "too US-centric" in a meeting of the International Astronautical Congress on Monday, adding that "Russia is likely to refrain from participating in it on a large scale."

Sergei Karpukhin/Reuters

"The most important thing here would be to base this program on the principles of international cooperation which were used in order to fly the ISS program," Rogozin said, according to SpaceNews.

In fact, NASA is using the same intergovernmental legal framework that it used for the ISS, Bridenstine said in a statement responding to Rogozin's comments.

Bridenstine also pointed to the Artemis Accords' clause on interoperability, which would ensure that future lunar-exploration infrastructure is easy for Russian technology to plug into.

"I don't think that there's any reason to think that we're not inclusive enough. In fact, what we're trying to do is create the most inclusive, most transparent path to the moon," he told reporters.

Gold said that more nations would join the accords soon, possibly by the end of the year. It seems unlikely that Russia or China will be in that group.

"There are many other nations that are not only interested in the Artemis Accords, but anxious to sign the Artemis Accords," Bridenstine said. "But countries all around the world have to go through their own interagency processes to be able to sign onto the accords. These first eight countries are the ones that were able to get through the interagency process the quickest."