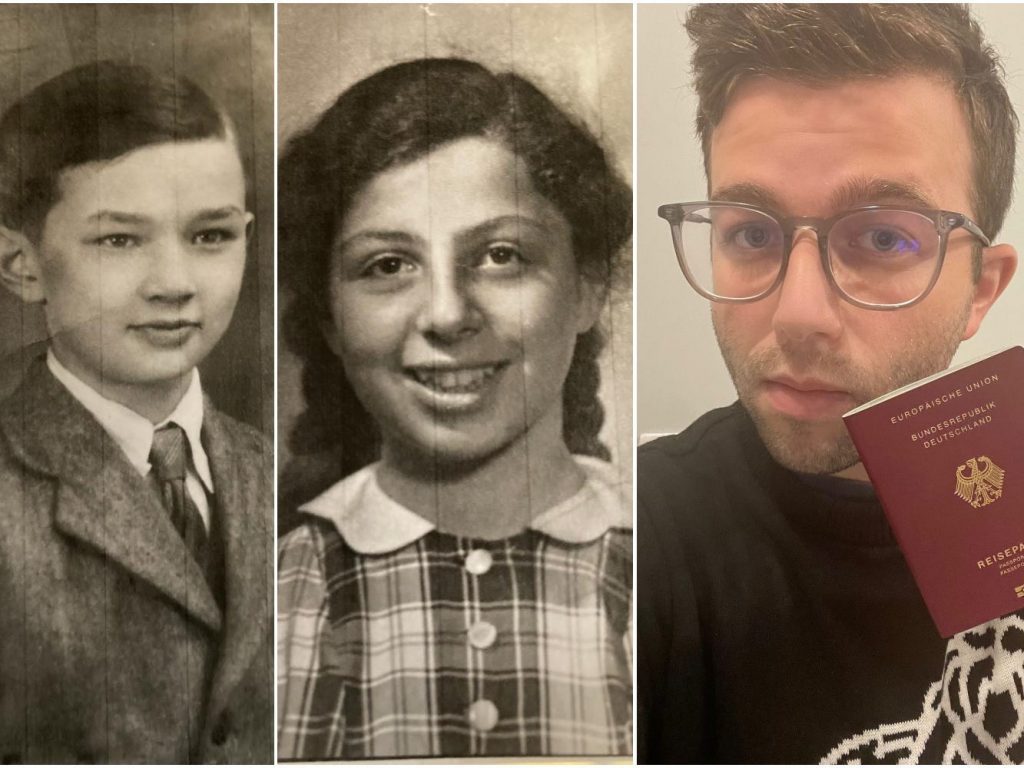

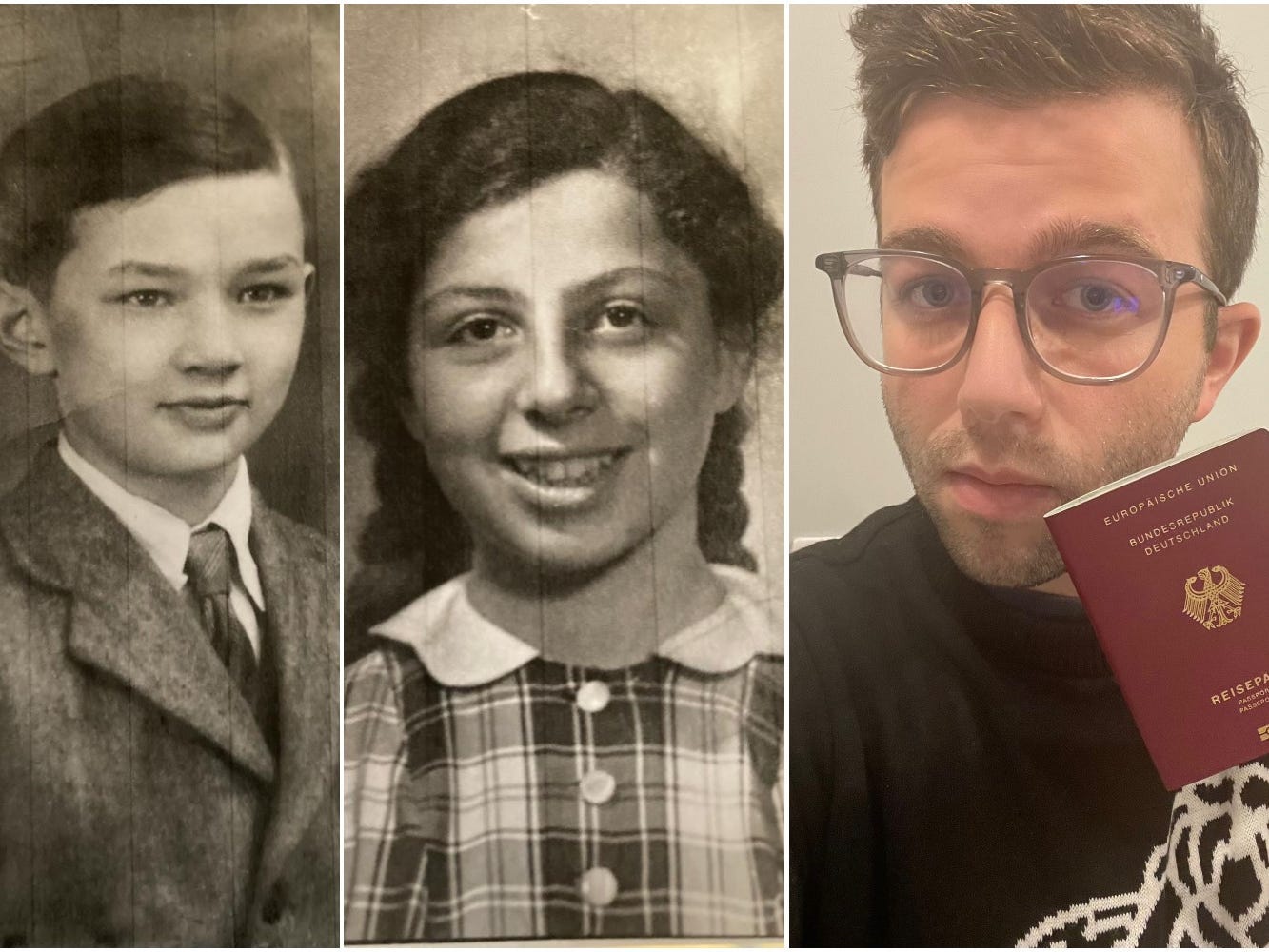

- My maternal grandparents, both Holocaust survivors, were stripped of their German citizenship by the Nazis.

- In 2021, I used a specific German law to "restore" my citizenship. I now have a German passport.

- Since 2016, approximately 7,320 have applied for German citizenship.

As my mother and I sat in an office at the German Embassy in the Belgravia district of central London, having just been handed a pack of Haribo, a Bundesflagge pin, and our citizenship papers, we looked at each other contemplatively.

We were officially German.

This moment was the culmination of three years of bureaucracy that, of course, does not befit the national stereotype of efficiency.

But while three years felt like forever and a day, restoring my German citizenship had actually been a much longer time coming for my family.

Some 80 years after my Jewish grandparents had their citizenship stolen from them, the result of numerous discriminatory laws passed by the Nazis during the Third Reich, we had reclaimed what was rightfully ours.

'This must have been a really difficult decision for you both'

Under German law, specifically Article 116, descendants of those who fled Nazi persecution — most of whom are of Jewish heritage — are allowed to "restore" their citizenship and, in turn, claim German passports.

The Federal Office of Administration in Germany told Insider that approximately 830 British people had applied for naturalization under Article 116 in 2021. Since 2016, approximately 7,320 have applied. The vast majority, 90%, have successfully become naturalized, the agency said.

As my mother and I signed the legal documents in July, marking the end of the application process to confirm our Germanness, a diplomat uttered something that unexpectedly, and instantly, gave me goosebumps. "This must have been a really difficult decision for you both," she said, sympathetically.

It felt empowering to, with just one stroke of a pen, close the door on a tragic chapter of my family history. But was it difficult for me? Not really.

I was fortunate enough that my beloved grandparents — Marlene, an Auschwitz survivor, and my grandfather John, a Kindertransport survivor — had given us their blessing to proceed with restoring our citizenship before they died.

They were of the mentality that I had every right to claim what I was owed, and that it would be useful for me to have a German passport after the UK withdrew from the European Union.

Having an EU passport allows me, in the long term, to easily live, work, and study abroad in the 27 member states. In effect, I could stay in France, Portugal, Poland or Italy, for example, for as long as I want.

My grandparents, seeing the practical benefits, were very pragmatic about it all. This made my decision relatively easy.

But for other British people of Jewish heritage who are also entitled to reclaim citizenship, the decision to become German is a much thornier issue.

'Any British person who applies for German citizenship is effectively forgiving Germany'

For Karen Millie-James, an author and business consultant from London, it's something she says she "could not ever countenance doing." Her grandparents, aunts, and uncles — all from Berlin — were murdered by the Nazis.

And her father, Roger, who was able to escape and moved to London, harbored a lifelong distrust of Germany.

Millie-James recalls growing up in a home where her father's traumatic relationship with the nation responsible for his relatives' deaths meant she once had to return a German-made radio she had purchased. "We weren't allowed to have anything German in the house," she said.

Millie-James called the idea of applying for a German passport "abhorrent" given what her father went through. "I couldn't do it in his memory," she added.

This sentiment is echoed by some vocal members of Facebook groups for the British Jewry.

"Any British person who applies for German citizenship is effectively forgiving Germany for the Shoah," said a member of "Jewish Britain" — an online community of more than 10,000 members. The Shoah is the Hebrew word for the Holocaust.

"To apply for a German passport is to declare that you feel a greater affinity — perhaps even loyalty — to Germany than to Britain," the comment continued.

'In a very tiny way, this is me striking back at Hitler'

Adrian Goldberg, a journalist in Birmingham who hosted a three-part BBC docuseries on the so-called "Deutschland Dilemma," told Insider he had to do a lot of "soul-searching" to determine whether he was making the right decision by applying to be recognized as German.

"It's quite a big thing to say that you want the association with the nation that killed my grandparents and killed a number of other members of my broader family," he said. "So, I thought, how do I square that with myself?"

He said one motivating factor was reclaiming his heritage. "My dad has his German citizenship stolen from him by Adolf Hitler," Goldberg said. "So, in a very tiny way, this is me striking back at Hitler. Up yours, Hitler!"

Another incentive was Brexit, he said: "Not everybody who voted Brexit was a racist by any stretch, but there was a strain of racism and bigotry in the Brexit campaign that made me feel very uncomfortable as a second-generation migrant."

Noah Libson, 23, said he was also influenced by Brexit. He applied for German citizenship, which he was eligible for via his grandmother, in the immediate aftermath of the 2016 Brexit referendum.

"I decided that it was something I wanted to do, even just for the basic practicalities of having an EU passport," he told Insider. "You can't deny that there is a certain safety to having another passport and, you know, worst comes to worst knowing that at least I can live somewhere else."

While precise figures are not available from before 2016, a representative for the German Embassy in London said there was a significant uptick in applications to restore German citizenship after the Brexit referendum.

Libson said that while his mother recognized the advantages of having an EU passport after Brexit, she personally felt "uncomfortable" about becoming German and turned down the opportunity to claim citizenship.

This is emblematic, he said, of the differences in opinions that can arise within families about restoring citizenship.

Jacob Brunert, a 22-year-old university student, told Insider that certain members of his family were also skeptical of him becoming German.

He said he felt his intentions came into question most when he decided to take part in an Erasmus+ program to study abroad in Germany for a year in 2020.

"I've got members of my family who voiced concern that I was going back at all," Brunert said. "But for me, I really was enticed by exploring my past, my history, and, directly, getting a feel for what it's like to be Jewish in Germany today."

This represents 'quite a fundamental shift' in Jewish identity

According to Simon Albert, a lawyer in London, and Ruvi Ziegler, an associate professor in international refugee law at the University of Reading, the fact that thousands of British people of Jewish ancestry were seeking EU citizenship represented a "quite a fundamental shift" in identity.

"The British Jewish community went under the radar, so to speak, for 80 years, and tried to integrate as much as possible, and be as British as possible, and keep their foreign origins and all the rest of it on the down low," Albert told Insider. "It's now going 180 degrees, and people are getting those Austrian and German passports, or Czech, or Spanish, or Portuguese, or whatever it is, because of Brexit."

Albert and Ziegler run a project with the Jewish Historical Society of England that is charting the phenomenon. Participants in the initiative detail why they have chosen or declined the opportunity to seek out citizenship in another European country.

Ziegler said people seemed to be acting pragmatically, rather than actively seeking out a new nationality. Many applicants see a German passport merely as a "vehicle to becoming European," he continued.

"My unscientific estimation is that the vast majority of British Jews who have acquired European citizenship haven't moved to any other European country," Ziegler said. "So it's to give themselves the option and the opportunities that arise, rather than for immigration."

Reflecting on the year I became a German citizen, I am appreciative of the advantages afforded to me by having an EU passport.

But, perhaps more meaningfully, there's also power in reclaiming something my grandparents were deprived of.

A German word comes to mind — Schadenfreude (a pleasure derived by someone from another person's misfortune).

There's a joy in knowing that because the Nazis lost, my family was able to rebuild.