- Prosecutors working for the special counsel Robert Mueller filed new documents late Monday that laid bare a slew of significant revelations about their case against Paul Manafort, the former Trump campaign chairman.

- The judge presiding over Manafort’s case also signaled that the FBI’s searches of Manafort’s home and storage locker could be challenged if Mueller’s mandate was not properly defined at the time.

Sign up for the latest updates on the Russia investigation here »

The special counsel Robert Mueller’s office filed new court documents Monday night that revealed the extent of prosecutors’ interest in Paul Manafort, the chairman of Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign, and his connection to Russian interests.

Mueller’s office filed three motions:

- One 11-page filing opposed Manafort’s request for a bill of particulars, which is a detailed, formal written statement of charges against a defendant.

- The 33-page second filing opposed Manafort’s motion to suppress evidence obtained during an FBI search last May of a storage locker in Alexandria, Virginia, belonging to his consulting firm, Davis Manafort Partners Inc.

- The 23-page third filing opposed Manafort’s motion to suppress evidence obtained in a predawn raid on his home in Alexandria in July.

Among other things, prosecutors disclosed the following in the new filings:

- There could be three other categories of unknown criminal allegations against Manafort.

- Manafort interviewed with the FBI twice before he joined the Trump campaign.

- FBI agents who raided Manafort’s home in July were looking for records related to the June 2016 meeting among three Trump campaign officials – including Manafort – and Russian lobbyists offering dirt on Hillary Clinton, the 2016 Democratic presidential nominee.

- Mueller has reviewed details of Manafort’s relationship with the Russian-Ukrainian oligarch Oleg Deripaska.

- Contrary to media reports, Mueller’s office did not use a “no-knock” warrant to raid Manafort’s home.

What Manafort’s lawyers are trying to argue

Manafort's lawyers have mounted an aggressive defense against prosecutors in recent months.

Their strategy centers on establishing two things: that Rod Rosenstein, the deputy attorney general, gave Mueller an improper and overly broad mandate when he appointed him special counsel in May, and that Mueller overstepped that mandate by charging Manafort with crimes unrelated to Russian collusion.

In particular, Manafort's attorneys point to an August memo that Rosenstein sent Mueller as evidence that Rosenstein "got something wrong" when he tapped Mueller to oversee the investigation into Russia's meddling in the 2016 US election and whether the Trump campaign colluded with Russia to influence the outcome.

Almost three months after appointing Mueller, Rosenstein sent a memo to Mueller authorizing him to investigate specific allegations related to Manafort, including but not limited to his Ukraine lobbying work and possible collusion with Russia.

Manafort's main defense lawyer, Kevin Downing, suggested last week that Rosenstein sent the memo because he failed to properly outline the scope of Mueller's mandate at the time of his appointment, as required by Justice Department regulations.

The search of Manafort's storage locker happened on May 27, 10 days after Mueller's appointment. The FBI's predawn raid of Manafort's home was executed on July 26, one week before Rosenstein sent Mueller the memo about his mandate.

US District Judge Amy Berman Jackson hinted that the searches could be challenged if Mueller's mandate was not properly outlined at the time.

Unknown criminal allegations against Manafort

Manafort's attorneys contend that the materials seized from the FBI's predawn raid on his home violated his Fourth Amendment rights against unreasonable searches and seizures.

They also accuse prosecutors of seizing materials that fell outside the scope of the warrant authorizing the search.

In defending the raid, Mueller's team said the warrant and the subsequent search and seizure were supported by a 41-page affidavit describing "potential violations of approximately ten criminal statutes arising from three sets of activities."

The third recent court document goes into specifics about the three allegations against Manafort contained in the affidavit, but almost all the details are redacted.

Based on Rosenstein's memo, Mueller is authorized to investigate at least two threads related to Manafort: allegations of criminal activity arising from his lobbying work in Ukraine, and allegations of collusion with Russian officials as the Kremlin was trying to meddle in the 2016 US election.

The memo contained several other details about possible allegations that would lie within Mueller's scope, but they too were redacted.

Manafort spoke to FBI agents on 2 separate occasions before joining the Trump campaign

According to the court filings, the FBI interviewed Manafort on twice - in March 2013 and July 2014 - before he joined the Trump campaign in March 2016.

Rick Gates, the former Trump campaign deputy chairman who has long been an associate of Manafort's, also interviewed with FBI investigators in July 2014.

Gates pleaded guilty in February to two counts related to conspiracy and making false statements and is now cooperating with investigators.

When the campaign hired Manafort and Gates in March 2016, Manafort was known for having worked as a top consultant to former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych; Manafort is widely credited with helping him win the election there in 2010.

Yanukovych, a strongman and a prominent figure in the Party of Regions, was ousted in 2014 amid widespread protests against his Russia-friendly positions and his decision to back out of a deal that would have promoted closer ties between Ukraine and the West and distanced it from Russia.

In July, The New York Times reported that financial records Manafort filed in Cyprus showed he was $17 million in debt to pro-Russian interests when he joined the campaign. Shell companies connected to Manafort during his time working for the Party of Regions bought the debt, according to the newspaper.

Mueller confirms his interest in the June 2016 Trump Tower meeting

When FBI agents raided Manafort's home in July, prosecutors said the warrant allowed them to seize records that fell within 11 categories.

Among those were "communications, records, documents, and other files involving any of the attendees of the June 9, 2016 meeting at Trump Tower, as well as Aras and Amin [sic] Agalarov."

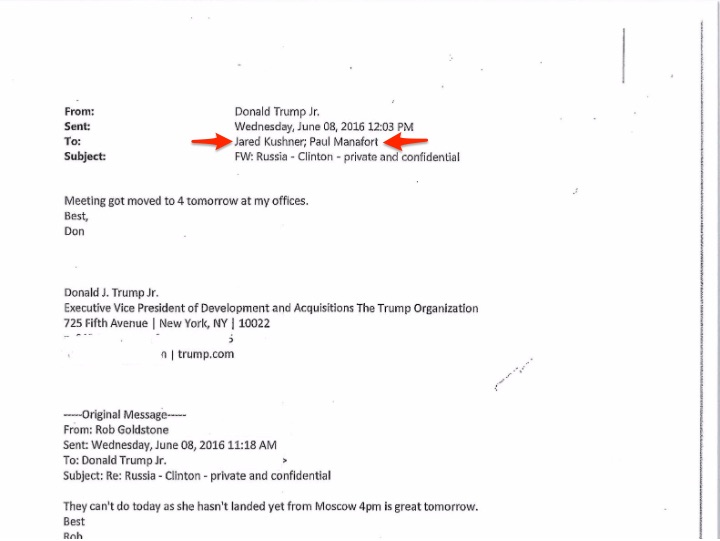

Three Trump campaign officials - Manafort; Trump's eldest son, Donald Trump Jr.; and Trump's son-in-law and senior adviser, Jared Kushner - met there with two Russian lobbyists who had offered dirt on Clinton. Reports of the meeting surfaced about three weeks before the raid.

The British music publicist who coordinated the meeting, Rob Goldstone, pitched it as "part of Russia and its government's support for Mr. Trump," according to photos of emails Trump Jr. posted on Twitter.

Trump Jr. has said that the Russian lobbyists did not provide the information to the Trump campaign and that the conversation instead centered on a 2012 law that blacklists wealthy Russians suspected of human-rights abuses and which the Russian government opposes strongly.

In addition to the meeting, Mueller is interested in Trump's role in crafting a misleading statement that Trump Jr. initially released in response to reports of the meeting.

The events are said to be a focus of Mueller's investigation into whether Trump attempted to obstruct justice.

Mueller zeroes in on Manafort's ties to Oleg Deripaska

Prosecutors said in Monday's court filings that in addition to seizing tens of thousands of records from Manafort's home last year, they had also reviewed testimony he gave in a civil lawsuit in 2015 about a financial dispute with Deripaska, an aluminum magnate with close ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Deripaska's representatives said in legal complaints filed in the Cayman Islands in 2014 that Manafort had disappeared after Deripaska gave him and Gates $19 million to invest in a Ukrainian TV venture in 2007 that ultimately failed.

Last year, The Washington Post reported that beginning in April 2016, Manafort emailed Konstantin Kilimnik, a former Russian military intelligence operative, offering to give Deripaska "private briefings" about the Trump campaign.

Former intelligence officials told Business Insider that the offer was most likely part of Manafort's effort to resolve his financial dispute with Deripaska.

Manafort and Kilimnik met in May and August 2016.

Manafort said that during the August meeting he and Kilimnik discussed the Trump campaign and the recent hack of the Democratic National Committee. Kilimnik has said they did not discuss the campaign but talked about "current news" and "unpaid bills."

Vice News reported last month that within hours of the meeting, a private jet linked to Deripaska arrived in Newark, New Jersey, close to where Manafort and Kilimnik met, and left within a day.

Agents did not use a 'no-knock' warrant to raid Manafort's home

Multiple media reports last year said FBI agents used a so-called no-knock warrant to execute the predawn raid of Manafort's home. But Mueller's team said in Monday's filings that its application for a search warrant "had not sought permission to enter without knocking."

"In issuing the warrant, the magistrate judge authorized the government to execute the warrant any day through August 8, 2017, and to conduct the search 'in the daytime [from] 6:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m.,'" the document says. "The government complied fully with those date and time conditions, and Manafort does not contend otherwise."

A possible complication for Mueller

The FBI's search and seizure of materials from the storage unit belonging to Manafort's firm is central to his defense.

The legality of the search is focused on the authority of a former employee of Davis Manafort Partners, to approve the search.

According to an earlier court filing, an FBI agent searched the storage locker on May 26 after obtaining permission from a "low-level" employee responsible for carrying out administrative functions.

The FBI agent then "observed a number of boxes and a filing cabinet" and "some writing on the sides of some boxes," the document says. The agent returned on May 27 with a search warrant relying on information he had surmised when he visited the storage locker the day before and subsequently seized documents and binders from the property.

Manafort's attorneys argue the evidence in question should not be used in court because the initial search was conducted without a warrant. They have also argued that the later warrant was too broad and amounted to a carte blanche in violation of Manafort's Fourth Amendment rights.

But Mueller's team contends the search was lawful because the employee signed the lease for the storage unit and had a key for the locker.

"The employee thus had common authority to consent or, at a minimum, apparent authority to do so," Mueller's team said in the earlier court filing. "Manafort 'assumed the risk that [the Employee] would' use the key he possessed to 'permit outsiders (including the police) into the' unit."

Prosecutors also argued that even if the FBI agent's initial visit to the storage locker was illegal, the May 27 search was legal because the FBI already had enough evidence beforehand to support its application for a warrant.