- A group of online conspiracy theorists claim that a type of toxic bleach is a wonder-cure they call Miracle Mineral Solution (MMS).

- The substance has been propped up by a video the Red Cross may have been tricked into helping make. The charity now says it “does not support or endorse in any manner” the claims made on the video.

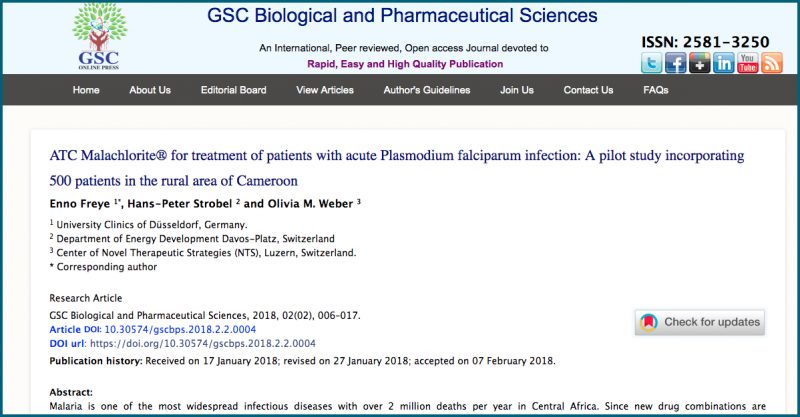

- MMS advocates also cite a questionable scientific study to support their claims.

- The study is by Dr. Enno Freye, an appellate professor at Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf, Germany.

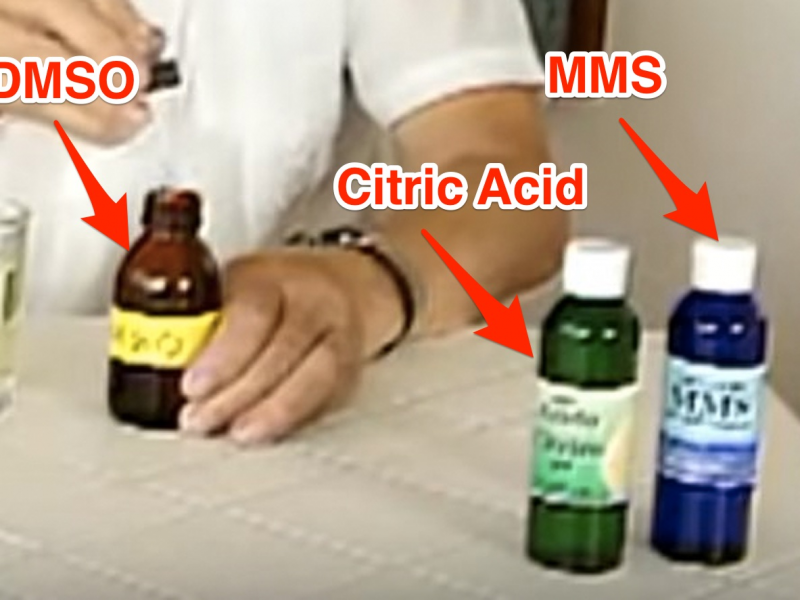

- In the study, he claims to have cured malaria patients using a substance made of sodium chlrorite and citric acid, the main ingredients of MMS.

- Business Insider asked Freye’s university about the study, which said it had stripped him of his academic title and disavows his study.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Weeks before his arrest in Uganda in June for allegedly distributing toxic bleach to people with malaria, British man Sam Little explained to Business Insider why he thought the substance was a wonder cure.

Chlorine dioxide – a constituent of so-called Miracle Mineral Solution – has been flagged as dangerous, even deadly, by health authorities around the world and has no foothold in conventional medicine.

Despite this, Little and others like him believe it has curative powers broad enough to heal autism, malaria, and also AIDS.

Little is now in custody in Uganda, after being arrested by authorities there in connection with allegations he distributed MMS.

But, speaking to Business Insider before his arrest, Little justified his belief three ways.

First, from experience (he says it cured his dog). Second, a pro-MMS video involving the Red Cross (which Business Insider debunked here). And, thirdly, an obscure scientific paper published in 2018 under the name Dr. Enno Freye.

To the untrained eye, the February 2018 paper, published by the journal GSC Online Press, appears to be a legitimate work of science.

Freye bears a distinguished academic title: Appellate Professor at Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf, Germany. In the paper he describes discovering a new way of treating malaria using a mixture of drugs.

Ferric Fang, a professor of laboratory medicine and microbiology at the University of Washington School of Medicine, told Business Insider that GSC Online Press is not a well-known journal in scientific circles, and questioned how it establishes whether the studies it publishes are scientifically valid.

But Little is not the only one to be taken in. Pepijn van Erp, a Dutch blogger who highlights disinformation around MMS, told Business Insider that other MMS proponents have also circulated the study via social media, the method by which much of the advocacy for the substance spreads.

Freye says he gave his substances to 500 patients in Cameroon, west Africa, though the exact location of the study isn't specified. The study describes giving doses of artemisin, a known anti-malaria drug, along with citric acid and sodium chlorite. Together the latter two form chlorine dioxide - the key components of MMS.

Freye and the two people named as co-authors of the study - Hans Peter Strobel and Olivia M. Weber - claim they were "able to reverse acute symptoms of malaria within the first 2 days."

But the study is not all it seems - and neither are Freye's claimed credentials. The story of how it came to be published and seized as proof by people peddling a dangerous bleach as cure illustrates the dangers of medical disinformation and how easy it is to spread.

Heinrich-Heine University spokeswoman Susanne Dopheide told Business Insider by email that the institution was aware of the study, which has "been reviewed by the medical faculty last year and have been found scientifically worthless, contradictory, and in part ethically problematic."

David Colquhoun, a Professor Emeritus of Pharmacology at University College, London, backed up the institution's findings about the study, and explained some of the red flags marking it out as fake science.

He described it in an email as "absurd (and very irresponsible)."

He pointed to the absence of a control group in the study, a breach of a "universal rule for any clinical trial."

A control is a parallel version of the experiment where the subjects are treated in exactly the same way as the main group in the study, but not subject to the substance that is the focus of the experiment.

This helps scientists to make sure the effects they measure are a result of the test, and not anything else. In medicine, patients are often given placebo drugs, and do not know they are part of the control group.

Colquhoun also highlighted a chemical flaw in the study. He said that the presence of artemisin -the anti-malarial drug - in the pills could have been responsible for any apparent recovery in the results.

He asked why patients weren't asked to sign an informed consent form before taking chlorine dioxide, the toxic bleach.

"The trial should, like any other, have been registered before it started. It wasn't," wrote Colquhoun. He pointed out that the authors also said they would publish the full results of the test - but that the results never materialized.

Professor Fang of the University of Washington also denounced the study.

"The use of highly toxic chlorine dioxide, a constituent of quack remedies, is, of course, a red flag," he said.

Fang also noted that "there are no published pre-clinical studies of the agent for the treatment of malaria in the conventional scientific literature."

Cameroon's health ministry did not respond to several requests for comment.

Academic title revoked

Freye's career, as described on online profiles, has been long. He has published papers spanning several decades, and made a recent foray into dietary supplements.

He describes himself on a profile for ResearchGate, an online network for professional scientists, as a member of the faculty at Heinrich Heine University. His page on the social media network Prabook describes him as an instructor in the Department of Vascular Surgery.

But the institution stressed that Freye was not an employee. The university told Business Insider that Freye had "never worked there" and that "his connection to the department [of vascular surgery] was purely advisory."

According to Dopheide, the university spokeswoman, Freye worked as an anesthetist at the university hospital from 1967 to 1981, and was appointed "appellate professor" in 1987.

She said his "connection to the department [of vascular surgery] was purely advisory, i.e. concerning publications of department."

She said that the title "appellate professor" is awarded to those "who fulfil the formal requirements to work as regular professors and accomplish an extraordinary level of research and teaching."

Dopheide said the university in February reviewed Freye's study, and other recent published work. It found it "methodologically erroneous," and stripped him of the appellate professor title.

"It violates fundamental principles of good scientific practice, e. g. lacking citation, and is therefore invalid," she continued.

"His publications have no scientific significance and damage drug research in general. Because he is illegally using our institution's name, he also damages the reputation of our Medical Faculty. That is why we decided to withdraw his title."

She said that throughout the review process, the university had been unable to reach Dr Freye.

Business Insider has made numerous attempts to contact Dr Freye by phone and by email, through his online research profiles, through a postal address, and on LinkedIn, but has received no response.

Attempts to reach Strobel and Weber through their public profiles also met with no response.

Fang, the medicine and microbiology professor, told Business Insider that the speed with which the study was accepted for publication by GSC Online Press raised questions about whether the research had been reviewed by experts.

"This paper was 'revised' 10 days after submission and accepted 10 days later," he told Business Insider by email.

"This is too rapid for a legitimate review. If a journal really cares about the validity of the papers that it publishes, they can obtain any number of external reviews, including specialty reviewers such as statisticians, and has the prerogative to request primary data for review. That was obviously not done here."

He said that online publishing has seen the rise of dubious scientific journals with sham review processes.

"Most scientists simply ignore these journals, but it may be harder for lay readers to distinguish the wheat from the chaff. It is more important than ever for readers to have a finely-tuned BS meter," he remarked.

GSC Online Press defended its review practices in an email to Business Insider, and said it had been made aware of problems in the study published in Freye's name.

"We have taken necessary actions and communicated with author to provide proper justification and documentary evidences within 2 weeks to ensure reliability of reported results, otherwise article will be retracted on ethical ground. We are waiting for response from author," said a spokesperson.

"Before publication of the article it was reviewed by two independent reviewers and was accepted for publication after recommendation by both reviewers."

At the time of publication, the study remains online.

- Read more:

- Amazon pulled a dozen books promoting toxic 'MMS' bleach as a cure for autism - but it had been warned months ago

- Promoters of toxic bleach targeted African communities with their 'MMS' miracle cure using a video the Red Cross now disowns

- British man arrested in Uganda after promoting 'MMS' bleach as a cure for HIV and malaria

- How conspiracy theorists who claim drinking 'MMS' bleach is a cure for autism reached millions of people on YouTube