- China is assembling a massive trade project – the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – which aims to connect the country with new infrastructure.

- Many of these projects pass through Xinjiang, a region in western China home to the beleaguered Uighur Muslim people.

- Beijing has been cracking down on Uighur life in on Xinjiang. Officials say its repression is a necessary counter-terror operation, but experts say it’s actually to protect their BRI projects.

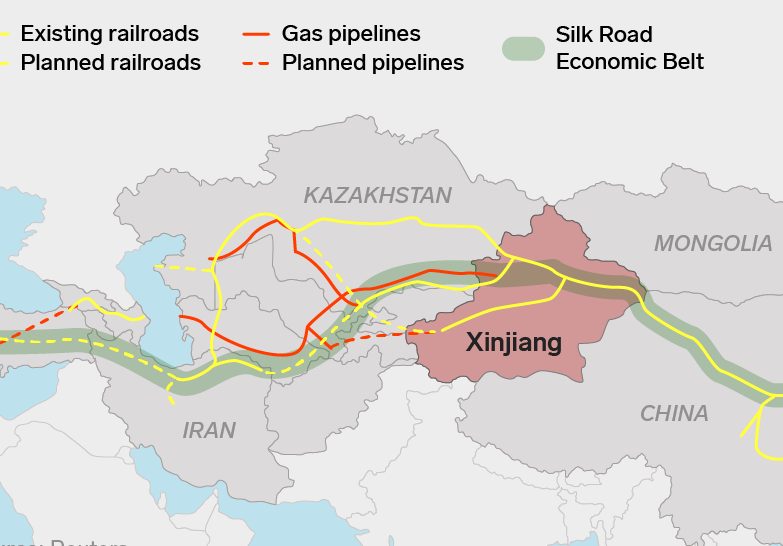

The Uighurs, a mostly-Muslim ethnic minority in Xinjiang, western China, are living in one of the most heavily-policed and oppressive states in the world. This map helps explain why.

People in Xinjiang are watched by tens of thousands of facial recognition cameras, and surveillance apps on their phones. An estimated 2 million of them are locked in internment camps where people are physically and psychologically abused.

China’s government has for years blamed the Uighurs for a terror, and say they saying the group is importing Islamic extremism in Central Asia.

But there’s another reason why Beijing wants to clamp down on Uighurs in Xinjiang: The region is home to some of the most important elements of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s flagship trade project.

The BRI, which went into effect in 2013, aims to link Beijing with some 70 countries around the world via railroads, gas pipelines, shipping lanes, and other infrastructure projects. It is considered President Xi Jinping's pet project, and an important part of his political legacy.

The map above shows Xinjiang's position along various BRI infrastructure projects.

A trillion-dollar reason to crack down on Xinjiang

It is divided between six land routes, collectively named the Silk Road Economic Belt, and one maritime route, the Maritime Silk Road. Xinjiang is home to many projects along the Silk Road Economic Belt, as the map indicates.

China is estimated to have invested between $1 trillion and $8 trillion into the project, the Center for Strategic and International Studies said.

Trade in goods between China and other countries along the BRI totalled $1.3 trillion in 2018 alone, the state-run Xinhua news agency reported, citing China's Ministry of Commerce.

Experts point out that China's growing emphasis on BRI projects coincides with Beijing's crackdown in Xinjiang.

China has accused militant Uighurs of being terrorists and inciting violence across the country since at least the early 2000s, as many Uighur separatists left China for places like Afghanistan and Syria to become fighters.

But its campaign of repression only stepped up in the past two years, under the rule of Chen Quanguo, a Communist Party secretary who previously designed the program of intensive surveillance in Tibet.

Normal people in Xinjiang have found themselves disappeared or detained in internment camps for flimsy reasons, like setting their clocks to a different time zone or communicating with people in other countries, even their relatives.

Rushan Abbas, a Uighur activist in Virginia, told Business Insider: "This has everything to do with the Xi Jinping's signature project, the Belt and Road Initiative, because the Uighur land is in the heart of the most key point of Xi Jinping's signature project."

Abbas is one of many Uighurs abroad currently swept up in China's mission to silence Uighurs. Her sister and aunt went missing in Xinjiang cities six days after Abbas criticized China's human rights record in Washington, DC. She believes her family's disappearance is a direct consequence of her activism.

Adrian Zenz, an academic expert on Chinese minority policy, told The New York Times earlier this year: "The role of Xinjiang has changed greatly with the BRI," and that China's ambitions have turned Xinjiang into a "core region" of economic development.

Foto: Uighur activist Rushan Abbas (right) and her sister Gulshan Abbas (left), in Virginia in 2015. Gulshan Abbas vanished in Urumqi, Xinjiang, in September 2018.sourceCourtesy of Rushan Abbas

Foto: Uighur activist Rushan Abbas (right) and her sister Gulshan Abbas (left), in Virginia in 2015. Gulshan Abbas vanished in Urumqi, Xinjiang, in September 2018.sourceCourtesy of Rushan Abbas

'Dog-and-pony shows' to Xinjiang

Beijing has made extra efforts to make sure countries involved in the BRI don't speak out about Xinjiang.

Since last December, Chinese authorities have invited dozens of journalists and diplomats from at least 16 countries - many of which, like nearby Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Pakistan, are taking part in the BRI - to highly-controlled tours of Xinjiang's re-education camps.

China has held up the tours as proof they have nothing to hide in the region. It euphemistically calls the camps "free vocational training" that make life "colorful."

Bizarre photos from the press trip show ethnic Uighur men and women putting on dance and musical recitals inside classrooms, operating sewing machines, and learning the words to pro-China songs from a textbook.

China is planning another trip later this month for diplomats from Pakistan, Venezuela, Cuba, Egypt, Cambodia, Russia, Senegal, and Belarus, Reuters reported.

But representatives from the United Nations and activists from groups like Human Rights Watch - who have campaigned, unsuccessfully, for access into the region - have not been invited.

Sophie Richardson, the China director for Human Rights Watch, wrote last month: "Beijing has a long history of diplomatic dog-and-pony shows, and the diplomats' visit is no substitute for a credible, independent assessment."

But the show tours have worked for some of those countries.

Mumtaz Zahra Baloch, the charge d'affaires at Pakistan's embassy in China, told the state-run Global Times tabloid: "Our visit reinforced my perceptions about this region that it has a multicultural and multi-ethnic identity, that it is critical for the development of the western regions of China and that it is an important node for regional connectivity under the Belt and Road initiative."

"Xinjiang is thus ready to play a critical role in the development of the Belt and Road initiative."