Most New Yorkers today are living on what was once farmland.

As early as the 17th century, before Manhattan formed its famous 1811 street grid, the island contained farms in neighborhoods from Midtown to the Upper West Side.

The Museum of the City of New York’s online collection reveals what the city looked like at the time. The series, “The Greatest Grid,” features illustrations and photos of New York City’s former rolling hills, which were later demolished to create a flat streetscape.

Take a look at the city’s transformation:

The Bowery is the oldest thoroughfare on the island of Manhattan.

When the Dutch settled there in 1654, they named the path Bouwerij - an old Dutch word for "farm" - because it connected cattle farms and estates on the outskirts to (what is today) Wall Street.

Source: The Encyclopedia of New York City

At the time, New York City (then known as New Amsterdam) featured rolling hills, forests, boulders, farms, and spaced-out homes. This 1776 illustration is of present-day University Heights in the Bronx.

Source: New York Public Library

Between 1818 and 1820, American surveyor John Randel Jr. prepared an atlas of 92 watercolor maps that illustrates the farm properties and old roads of pre-grid Manhattan (planned in 1811) as well as the future location of the new streets and avenues. The Museum of the City of New York stitched them together to create a map, pictured below:

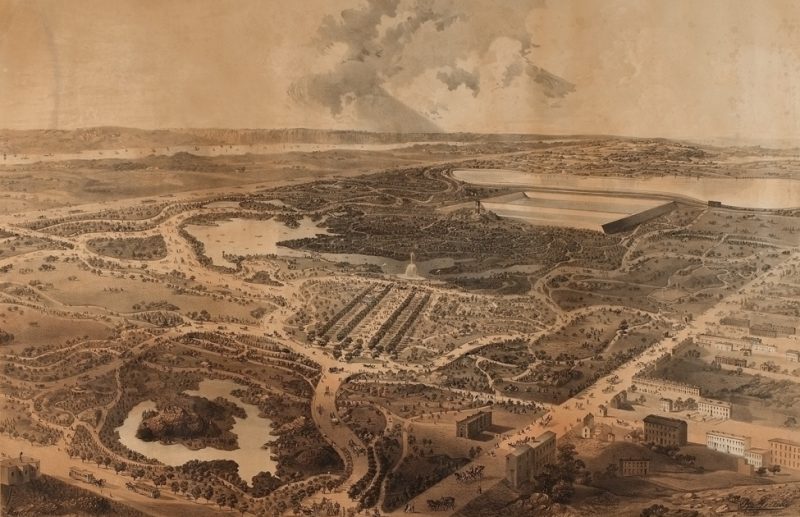

This 1862 illustration depicts a triangular farm on Manhattan's Upper West Side during the Civil War. High property taxes discouraged landowners from building on their lots, and the area would not see full-scale development until the 1880s.

Source: The Museum of the City of New York

Sheep grazed on west Central Park's Sheep Meadow from the 1860s until 1934, when they were moved to Brooklyn's Prospect Park and later to a farm in the Catskill Mountains.

Source: Modern Farmer

The sheep's owners relocated them because they feared that impoverished New Yorkers would eat the animals. City officials also wanted to build through-roads and the Tavern on the Green restaurant there.

Source: NYC Travel Guide

Beginning in the mid-19th century, Manhattan started demolishing the area's hills — and thus farmland and some farmhouses — to make way for the city's level thoroughfares.

Source: Museum of the City of New York

This 1869 photo shows a team of laborers excavating through a hillside to extend Eighth Avenue north.

Source: The Museum of the City of New York

Bedrock that could not be cleared by shovel and pickaxe required gunpowder.

Source: The Museum of the City of New York

Since lot owners were not required to level the bedrock to the street grade, some left large boulders, as seen in this 1903 photo:

Source: The Museum of the City of New York

In this 1869 painting, artist Alessandro E. Mario portrays the transformation of New York from farmland to a city as an almost biblical pursuit. From an aerial vantage point, the viewer looks down at laborers chiseling rock with hand tools and riding horse-drawn carts.

Source: The Museum of the City of New York

"The time will come when New York will be built up, when all the grading and filling will be done, and when the picturesquely varied, rocky formations of the Island will have been converted into formations for rows of monotonous straight streets, and piles of erect buildings," Frederick Law Olmsted, an NYC landscape architect, wrote at the time.

Source: The Museum of the City of New York

In this 1878 photograph, you can see the remains of a house atop a rocky outcropping on what is today Harlem's Morningside Park. At this time, the area was still dominated by farms, squatter settlements, and the villages of Manhattanville, Harsenville, and Carmansville.

Source: The Museum of the City of New York

Land auctions moved from the Merchant Exchange's basement to the Real Estate Exchange near the southern tip of Manhattan in 1885. The new facility represented a professionalization of the real-estate business, which had previously suffered from bogus sales and other shady practices.

Source: The Museum of the City of New York

In 1864, The New York Times estimated that 20,000 squatters, who faced a constant cycle of eviction and resettlement, lived in Manhattan. As the city grew northward, German and Irish immigrants unable to find affordable housing built wooden shacks.

Source: The Museum of the City of New York

Many raised chickens and pigs, and grew vegetables to sell at local markets. Documentary photographer Jacob Riis captured one of these shantytowns, erected on a rocky outcropping, in the 1896 photo below. A woman to the right tends to her goats.

Source: The Museum of the City of New York

Since much of the land was dug up, it became increasingly difficult for farmers to raise livestock and grow crops. Down second Avenue on Manhattan’s east side, some older homes remained until the late 1800s on top of hills that had not yet been leveled with the street grade.

Source: The Museum of the City of New York

Patrick and Mary Brennan's farmhouse, pictured below in 1879, lasted until about 1900. Edgar Allan Poe rented a room there, where he most likely wrote "The Raven."

Source: The Museum of the City of New York

This photo was taken in 1882 from the roof of a mansion that belonged to George Ehret, a successful brewer and one of the first wealthy New Yorkers to move to Prospect Hill (now Carnegie Hill).

Source: The Museum of the City of New York

The photographer Peter Baab captured what he called the "march of improvement." New row houses and mansions began to overrun the old factories, squatter homes, and farmhouses that once dominated the Upper East Side.

Source: The Museum of the City of New York

In the late 19th century, the city pushed to urbanize, and urban livestock — including hogs and dairy cows — were seen as a threat to the image and highbrow future of New York. According to CityLab, many members of Manhattan's elite bought (or took) the city's farmland, often owned by those of lower status, during this period.

Source: CityLab

Irish pig farmers and German gardeners, as well as the African-American settlement of Seneca Village, worked and lived on the land that's known today as Central Park. Most of their homes were destroyed in the 1860s to create the park.

New York's wealthy mostly funded the city's parks and public spaces, in hopes of creating places where upper-class women could stroll without coming into contact with people of lower status, according to historians.

In this photo from 1890, 94th Street cuts through a hill next to a farmhouse.

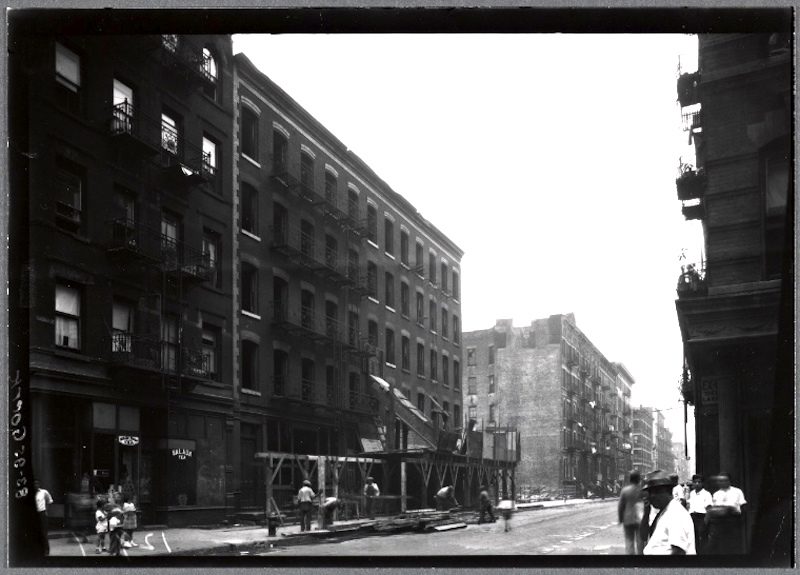

The newly graded streets attracted residents to upper parts of Manhattan. Within two decades, apartment buildings replaced the farmhouses in this 1898 photo.

New York's street grid became denser throughout the early 20th century. Though the grid was great for housing, city commissioners soon realized the master plan — and high land values — deprived residents of space and sunlight.

The city moved toward a more modern urban plan called superblocks, which required demolishing tenement buildings and constructing larger apartment buildings with spacious green areas in between. But New York City will most likely never be as grassy as it used to be.