- Some early studies have suggested that coronavirus antibodies fade relatively quickly, but that doesn’t mean immunity vanishes.

- A new study found that all participants infected with COVID-19 – even those with asymptomatic or mild cases and patients who didn’t have detectable antibodies – developed virus-specific T cells.

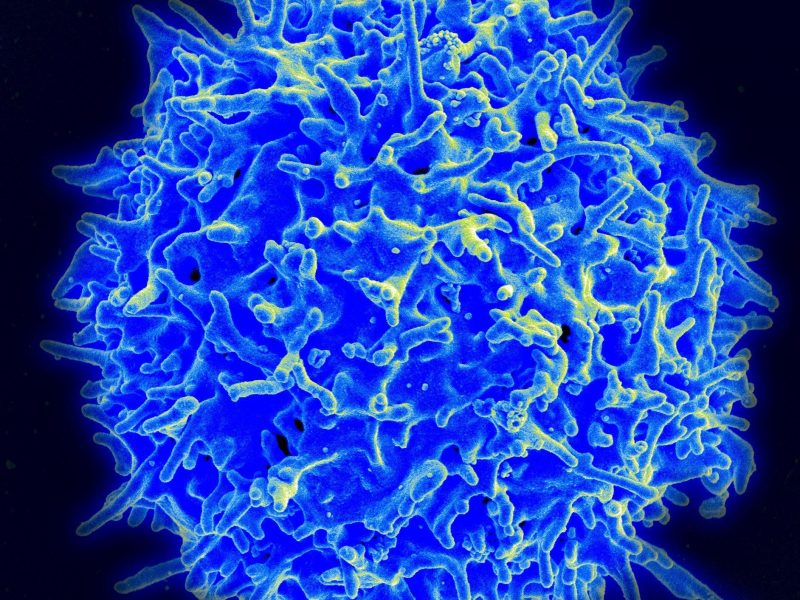

- T cells identify and kill infected cells, and B cells create new antibodies. Those cells can attack the virus if it ever returns.

- So the new finding is strong evidence that all patients likely develop long-term immunity.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Scientists may now have an answer to one of the most crucial lingering questions about COVID-19: whether people develop long-term immunity.

Early research suggested that coronavirus antibodies – blood proteins that protect the body from subsequent infections – could fade within months. But in their concern about those findings’ implications, many people failed to consider our immune system’s multilayered defense against invading pathogens.

Specifically, they discounted the role of white blood cells, which have impressive powers of recollection that can help your body mount another attack against the coronavirus should it ever return. Memory T cells are an especially key type, since they identify and destroy infected cells and inform B cells about how to craft new virus-targeting antibodies.

A study published Friday in the journal Cell suggests that everyone who gets COVID-19 – even people with mild or asymptomatic cases – develops T cells that can hunt down the coronavirus if they get exposed again later.

"Memory T cells will likely prove critical for long-term immune protection against COVID-19," the study authors wrote, adding that they "may prevent recurrent episodes of severe COVID-19."

That's because memory T cells can stick around for years, while antibody levels drop following an infection.

Even patients without antibodies have virus-specific T cells

The authors of the new study examined blood from 206 people in Sweden who had COVID-19 with varying degrees of severity. They found that regardless of whether a person had recovered from a mild or severe case, they still developed a robust T-cell response. Even coronavirus patients who did not test positive for antibodies developed memory T cells, the results showed.

Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, called T-cell studies like this one "good news."

"There's a lot of hot stuff going on right now" in T-cell research, Fauci said during a NIAID Facebook Live interview on Thursday, adding, "People who don't seem to have high titers of antibodies, but who are infected or have been infected, have good T-cell responses."

Other recent research bolsters the new findings.

A study published in July found that in a group of 36 recovered coronavirus patients, all produced memory T cells that recognize and are specifically engineered to fight the new coronavirus. Another recent study published in the journal Nature found that among 18 German coronavirus patients, more than 80% developed virus-specific T cells.

Even people who've never been exposed to the new coronavirus can have protective T cells

Both of those previous studies yielded a more surprising finding as well: Many people who've never gotten COVID-19 seem to have memory T cells that can recognize the new coronavirus.

That was true for more than half of a cohort of 37 people in the July study and at least one-third of a group of 68 patients in the Nature study.

The likeliest explanation for these findings is a phenomenon called cross-reactivity: when T cells developed in response to another virus react to a similar but previously unknown pathogen. In this case, experts think these cross-reactive T cells likely come from previous exposure to other coronaviruses - those that cause common colds.

Indeed, a study published earlier this month supports that hypothesis: Researchers reported that 25 people who'd never had COVID-19 had memory T cells that could recognize both the new coronavirus and the four types of common-cold coronaviruses equally well.

"This could help explain why some people show milder symptoms of disease while others get severely sick," Alessandro Sette, a coauthor of that study, said in a press release.

"You're starting with a little bit of an advantage - a head start in the arms race between the virus that wants to reproduce and the immune system wanting to eliminate it," Sette previously told Business Insider.

We still don't know precisely how long this long-term immunity lasts

Though this news about T cells and coronavirus immunity is promising, scientists still don't know precisely how long people who recover from COVID-19 will be protected from future infection.

The authors of the new study said they detected T cells "months after infection, even in the absence of detectable circulating antibodies."

Other preliminary research published Saturday suggests that T cells not only last at least three months after coronavirus symptoms start, but in some cases also increase in number during that time.

What's more, clues gleaned from other coronaviruses, like SARS, suggest T cells' lifespan could be decades long.

The July study also looked for T cells in blood samples from 23 people who survived SARS. Sure enough, those survivors still had SARS-specific memory T cells 17 years after getting sick. Those same T cells could recognize the new coronavirus, too.