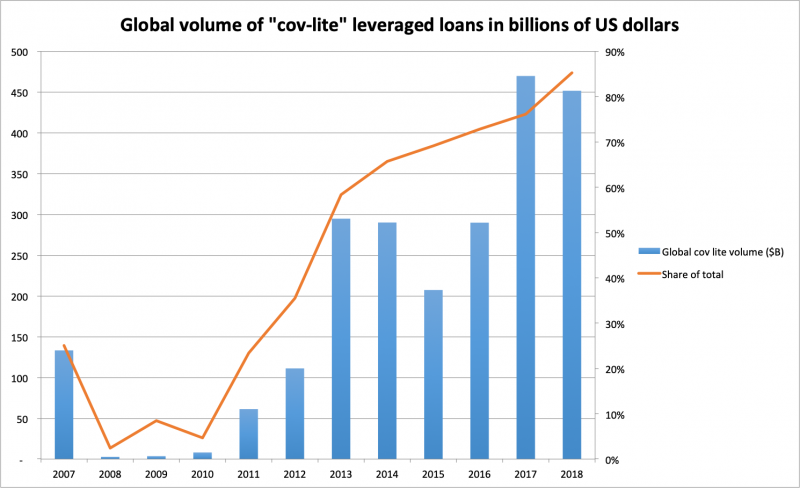

- 85% of all leveraged loans – one of the most-risky types of corporate debt – are now “covenant-lite.”

- That means they lack traditional requirements for companies to maintain certain financial benchmarks that protect the investors who pay for them.

- Leveraged loan quality is thus at a record low.

- Bank of England Governor Mark Carney compared it to the subprime mortgage crisis of 2007.

The leveraged loan market just set a new record: The quality of investor protections in this market just hit a new all-time low.

By the end of last year, 85% of all leveraged loans – one of the riskiest types of corporate debt – were “covenant-lite,” according to the Leveraged Data & Commentary unit of S&P Global Market Intelligence. That means they lacked the traditional requirements for companies who take such loans to maintain or beat certain financial benchmarks.

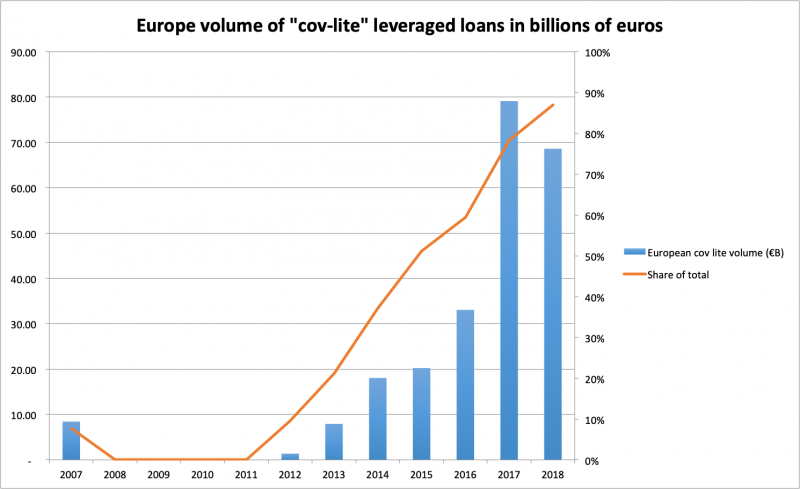

In Europe, the situation was even worse. 87% of leveraged loans were “cov-lite.”

As recently as 2011, only 23% of such loans were cov-lite.

Last year, $452 billion in new cov-lite issuance was added to the market. That number was down from the $470 billion issued in 2017.

The scale of the problem has worried Bank of England Governor Mark Carney.

The market is awash with "80% cov-lite, on the road to no-doc underwriting, which happened 11 years ago," Carney told parliament in January.

"No-doc underwriting" is a reference to the low standards of subprime mortgage lending that led to the financial crisis of 2007/2008.

"This is very clear evidence of a steady decline in underwriting standards. We are also concerned that the pace of growth has been quite rapid for some time," Carney added.

Leveraged loans are so called because they are often used by private equity groups to take over companies in leveraged buyouts (LBOs), or by companies who have run into trouble and are locked out of the higher quality corporate credit markets.

The "leverage" aspect comes from the notion that such loans are a bet on the future of the company.

A leveraged loan is risky because it is "leveraged" against the private-equity group's money and its ability to turn a struggling company around while paying off all the debt.

The loans are sold in packages (called collateralized loan obligations, or CLOs) to other investors much the same way as mortgages are bundled for people who want the stream of cash flows from a mortgage-debt investment. Lenders receive a high rate of interest because the risk of failure is comparatively high.

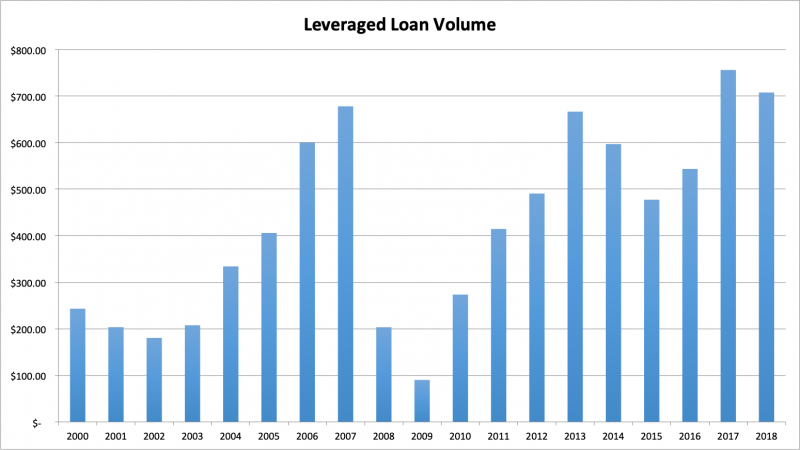

The total of outstanding leveraged loans on the market is around $1.6 trillion, but estimates vary. The total of leveraged loan new issuance - which includes types of loans not included in the above charts - was over $700 billion in 2018.

LCD/S&P analyst Ruth Yang, in a useful article assessing the cov-lite problem, points out that cov-lite on its own doesn't mean that a company's underlying credit is weak.

The market is aware that cov-lite is the default option for leveraged loans and has clearly accepted the situation, she says. But lack of covenants do deprive the market of an early warning system if things going wrong, she says:

"It is important to remember that in the rush to assess the health of this long-standing bull market, cov-lite in and of itself is not a sign of credit risk. Cov-lite simply means that maintenance covenants-a lender's early warning system-are no longer present, and that the loan market has adopted a bond market approach to covenants."

"If the underlying credit is healthy and the business model supports the issuer's ability to manage debt, the loss of maintenance covenants is moot. However, if credit quality is poor and market conditions weaken the performance of borrowers, cov-lite makes it more difficult for lenders to identify-much less intervene with and influence-weakening credits."

Read more:

The riskiest part of the corporate debt market is inching toward a historic danger signal

Investors just pulled out a record $13 billion from the shaky leveraged-loan market