- Biographer Ken Auletta discussed his upcoming book on Harvey Weinstein in a wide-ranging interview with Business Insider.

- Auletta talked about how he failed to crack the Weinstein story in 2002 and said he’s done 100 interviews for his upcoming book.

- He also talked about what’s wrong with journalism today and his career regrets.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

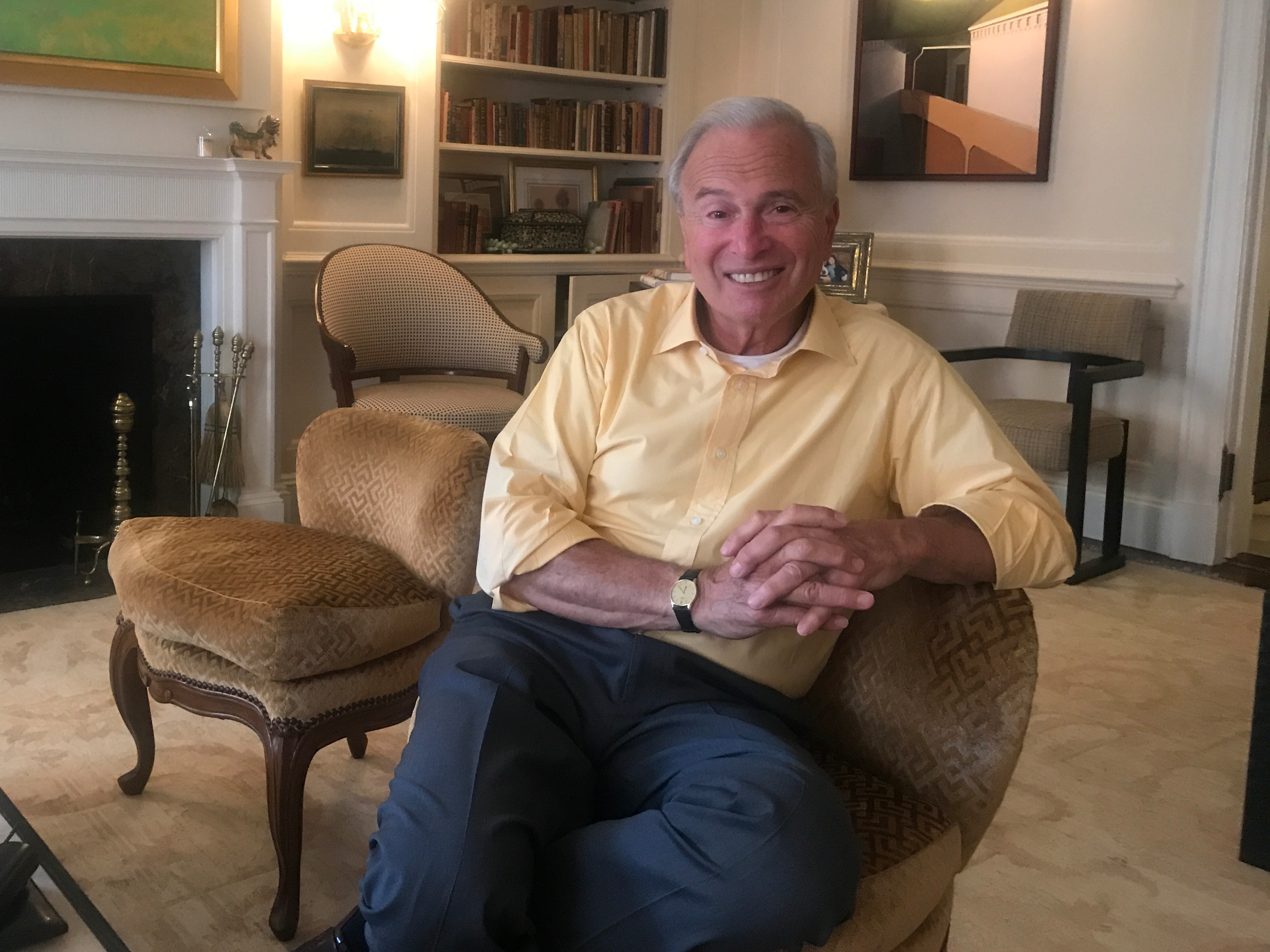

Veteran journalist Ken Auletta gave Business Insider a wide-ranging interview about his upcoming biography on Harvey Weinstein, what’s wrong with journalism today, his interviewing process, and career regrets.

“One of the things I try to tell people is… ‘I’m really trying to understand you,'” Auletta said of his interview subjects. “And I’m not lying. I really am trying to understand them. I’m not going in with a point of view.”

That’s the approach Auletta is applying to his Weinstein reporting, which he estimates has entailed 100 interviews so far. His book, slated for release in 2021, intends to cover the disgraced movie mogul’s life, from his early days in Flushing, New York, all the way to Hollywood and the Academy Awards. Auletta said he plans to explore the key events that shaped him, his legacy as a filmmaker, and trail of abuse left in his wake.

Read more: John Malkovich defends starring in a new play inspired by Harvey Weinstein: ‘It might upset people’

Ronan Farrow of The New Yorker and Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey of The New York Times, who broke news of the Weinstein allegations in 2017, also have books about Weinstein coming up.

Business Insider spoke to Auletta, 77, at his Upper East Side apartment. Our conversation was edited for clarity and brevity.

Casey Sullivan: How did you report the Weinstein book?

Ken Auletta: The last two weeks I probably spent most of my time interviewing people who he went to school with and trying to get inside his home and looking at pictures. There are lots of pictures on the internet. Harvey was not fat Harvey. He had a full head of hair. He had acne. And then you just interview people. People who worked for him. People who claimed they were raped by him. People who look at the impact he had on the movie business. I have about 15 hours of tapes from my interviews with him in 2002. I probably have about 100 interviews so far. Some people are afraid to talk. They don't want to be associated with Harvey Weinstein.

[Auletta profiled Weinstein in 2002 for The New Yorker but did not report on an allegation of rape because sources did not go on the record, he said.]

Sullivan: I remember after the [2017 Weinstein] story came out, the question became: Who protected him and who knew. What is your sense, from talking to as many people as you have?

Auletta says Weinstein had people who enabled him

Auletta: There is no question that Jodi Kantor and Meg Twohey will have a lot about enablers. And if I spent too much time on that, I'd be dated, because they're going to do a really good job on that. Ronan will have some of that. The people who worked for Harvey, they didn't know he was raping women or sexually molesting them. There were clearly some people who knew, who had a reasonable idea.

Sullivan: Have you interviewed Harvey?

Auletta: No. I have 15 hours of taped interviews with him from 2002. Right now Harvey is not one of my biggest fans, so right now he won't talk to me.

Sullivan: Why isn't he your fan?

Auletta: He didn't like the piece I wrote about him in 2002. He knows I went back, trying to report whether he was guilty in 2015 and 2017. And he knows that I introduced Ronan Farrow to The New Yorker.

Sullivan: Do you have any regrets for not pressing harder back in 2002?

Auletta on why he didn't report on Weinstein abuse back in 2002

Auletta: No. A) I think I wrote a pretty tough profile of the guy and explained someone who was pretty much out of control a lot of the time and abusive to people. In some cases, physically abusing people. Getting a reporter in a headlock and throwing punches at people and doing some of the things he is alleged to have done sexually. But I couldn't get women to talk. I give enormous amount of credit to the Times reporters and to Ronan for making them feel comfortable. Some people would say times change. You had Bill Cosby. You had Roger Ailes. And there's some truth to that. But the larger truth is their ability, their empathy, to get people comfortable enough to talk. Which is astonishing. And I applaud them.

Sullivan: You've covered the media for a long time. What changes get under your skin?

Auletta: A lot of things. BuzzFeed wrote about Facebook and what they have done in the Philippines. The president and his minions take over the internet and Instagram and they put up fake news about opponents. And it gets a lot of engagement. So Facebook loves that and the algorithms love that. That's worrisome - the power of the official platforms to distort the truth, relying on algorithms and the wrong way of measuring things and not relying on more expensive curators or editors.

We spend too much time with Donald Trump. I think Donald Trump is a liar. And I applaud the press for exposing his lies. On the other hand if you turn on CNN or MSNBC, it's all Donald Trump. CNN, which takes pride in saying they cover the world, they don't cover the world. They cover Donald Trump. You know why? A) he's appalling. B) he's really good for business. People are really interested.

I see straight reporters, really good reporters, getting paid to go on CNN or MSNBC and opine or sit with anchors who are opining all the time. I find it really excessive. And it contributes to the polarization of the Trump supporters, who don't believe what they read or watch in the Times or MSNBC. We are contributing to our own unpopularity. We are no longer perceived to be the referee.

Sullivan: What advice would you give to a journalist entering the job market today?

Auletta: I would make sure I was capable of multimedia tasking. I could use a podcast. I could use my iPhone to take photos. I could do everything. It used to be that we would have said, "Get a job at a town newspaper." Many of those local papers are gone now and so that's not an option. Digital publications become the new farm system.

Sullivan: Is there a risk to that, though? Those places you're talking about are New York and Washington-centric. Media becomes a pretty clubby environment.

Business models that work for digital media today

Auletta: It does. But I'm sure most people today will get hired from other publications based on what great work they do.

Sullivan: What do you consider high-paid position in journalism, in terms of salary?

Auletta: I think you're talking about the New York Times reporters ... 150 range, 130 range. Reporters are. I think that. And I'm sure reporters at many other publications get half that.

Sullivan: What business models do you see working in media now?

Auletta: The model for digital success is publications that rely less on advertising and more on the ability to raise subscriber prices. The Times has gone from 80% on advertising revenues to 40%. But the New York Times makes most of its profits in the print publication. If the print publication goes away, will digital revenue be able to sustain the New York Times?

The average advertiser who spends $10,000 for an ad in the print newspaper pays $1,000 to $1,500 for the same ad in a digital newspaper. So what everyone tries to do is throw stuff against the wall and see what works. Cruise ships. Wine selling. Selling your puzzles, your recipes. The Guardian asks you for a contribution at the end of each article. And they've done pretty well with that. But we're a beleaguered industry.

Sullivan: Who is your biggest mentor and what did that person teach you that was valuable?

Auletta: Richard Reeves. He gave me a lot of good tips about storytelling and reporting. Write like you talk. And don't clear your throat. Write like you're telling the story. Clay Felker, who always believed, have a strong lede that draws the reader in. I'm always looking for what that quintessential anecdote is that kind of sums up what the story is going to be about.

Weinstein had a big impact on the movies

Sullivan: What mistakes do you see young journalists making?

Auletta: They don't think about storytelling. Sometimes I read stories that have narrative but too little reporting. And I don't trust the facts. We live in a time where people are giving too much opinion and it intrudes on the storytelling. You want the reader to trust you. And if you burden them right away with your opinion, they're going to be skeptical.

And that's the thing with Harvey, I'm not a prosecutor. I'm going to tell this story and I'm going to tell his talent. And I won't do my job if I don't do that.

Sullivan: What effect did he have on the movie business?

Auletta: He did a lot of great movies. He made independent films. He changed the way the Academy Award campaigns are run. He treated them like political campaigns. That's raised a lot of criticism in the industry. He passionately cared about movies. He read books. He read scripts. He weighed in, often times in the right way in making the movie better. Sometimes they called him Harvey Scissor Hands. He was a micromanager. He drove Martin Scorsese crazy making "Gangs of New York."

But more often than not, Harvey was a constructive player. Part of his power was that they thought they would make a really good movie with Harvey. It might win an Academy Award and it could really further their career. They knew he was a great marketer.

When Ben Affleck and Matt Damon did "Good Will Hunting," other studios passed. And they sent the script to Harvey and he met with them and he said, "Guys, I love this, but you have this crazy sex scene in here that makes no sense and I'd urge you to take it out." And they said, "We want to work with you." They put the sex scene in to see if the studio guys would react. It wasn't really going to be part of the script. Nobody noticed it at the studios except Harvey.

Auletta on regrets about his journalism career

Sullivan: What was your biggest mistake as a journalist?

Auletta: With Elizabeth Holmes, I had some degree of skepticism, but John Carreyrou at The Wall Street Journal showed that she was doing fraudulent work. I didn't get that story. I have some regret about that.

I feel some regret about Bill Gates in that I wrote a book about him and the Microsoft trial and I portrayed him as childlike and that he could have settled with the government. I stand by that. But Gates doesn't talk to me. I feel bad. I would want to tell him that I respect what he's done since with philanthropy.

You sometimes write about people and they feel it's cruel. But part of doing access journalism is you spend real time with people. You've laughed at their jokes and you have wine at their dinners And these interviews, it's almost like you're their shrink. You're talking about their parents and their childhood. And then a piece appears and they feel betrayed. I understand that. I don't apologize for it, though.

As a journalist you have to be a good listener. One of the things I try to tell people is, "I'm really trying to understand you." And I'm not lying. I really am trying to understand them. I'm not going in with a point of view about that. Don't rush. If you're talking to someone let them talk and if there is a long pause don't interrupt them. And be empathetic.

Sullivan: So you spend your time trying to understand other people. If you were to turn that inward, what would you say makes you you?

Auletta: Standards, ethics is one. You don't take shortcuts. You don't lie to people. You don't trick them into talking to you. You say right at the beginning, this is on the record. An unwillingness to talk about myself. The story is not about me, it's about the other person.

Sullivan is joining Business Insider as a private equity correspondent.