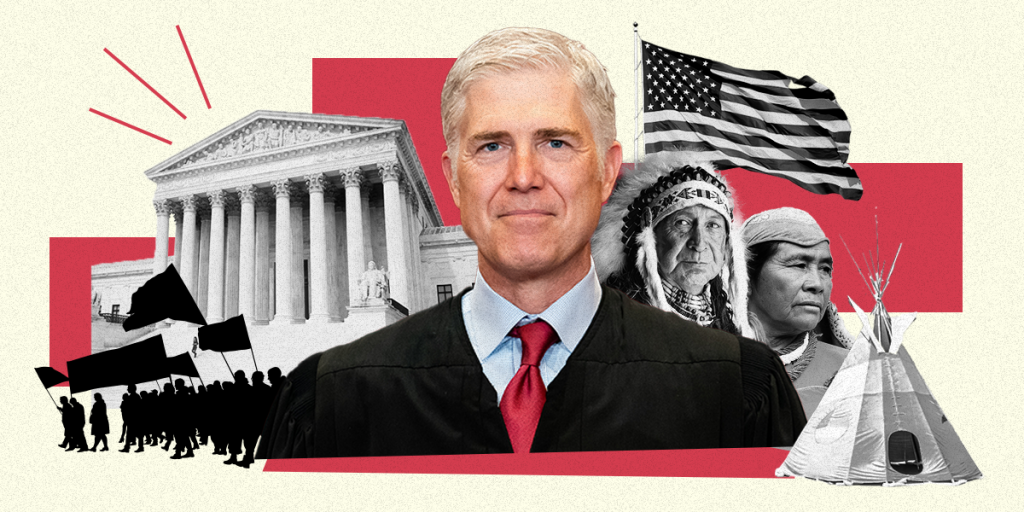

- In a recent dissent, Justice Neil Gorsuch blasted his conservative colleagues' ruling on Native law.

- As a judge in the West, Gorsuch was exposed to many cases involving tribes and Native people.

- Experts told Insider that background helped Gorsuch develop a deep understanding of Native law.

When Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch broke from his conservative colleagues last month on a case related to tribal sovereignty, he didn't just disagree with them — he bashed their entire understanding of Native law and all but accused them of contorting the law to reach an outcome they wanted.

"Truly, a more ahistorical and mistaken statement of Indian law would be hard to fathom," Gorsuch wrote in a scathing dissent, joined by the court's liberal wing. "Tribes are not private organizations within state boundaries. Their reservations are not glorified private campgrounds. Tribes are sovereigns."

The majority sided with the state of Oklahoma in the case, Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, holding that the state had concurrent jurisdiction with the federal government to prosecute some crimes committed on reservations. Like Gorsuch, Native law experts were stunned and dismayed by the ruling, which they said went against almost 200 years of precedent and weakened tribal sovereignty.

The part that wasn't surprising to the experts? That Gorsuch broke from his fellow conservatives.

"The majority opinion is a pretzel twisting itself to get to that outcome instead of letting it flow," James Maggesto, a lawyer who focuses on Native American law, told Insider. "The reason Justice Gorsuch gets these opinions right is because he's had experience in those circuit courts."

Maggesto, a member of the Onondaga Nation, said Gorsuch's background in the West and years of firsthand experience contributed to his deep understanding of Native law and the real-world implications of the court's decisions when it comes to Native people.

A Westerner on the High Court

Gorsuch grew up in Denver, Colorado. His family moved to Maryland when he was in his early teens and he attended Georgetown Prep, where he graduated two years after his future colleague, Justice Brett Kavanaugh. Like many Supreme Court justices, Gorsuch went on to the Ivy Leagues, including Colombia and Harvard Law.

But unlike many justices, Gorsuch moved back to his home state of Colorado in 2006 to serve as a judge on the US Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit. He spent the next decade on the circuit, which covers district courts in Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico, Utah, Kansas, and Oklahoma — in other words, lots of Indian country.

When Gorsuch was appointed to the Supreme Court in 2017, a former colleague, Michael W. McConnell, told The New York Times Gorsuch would bring a unique perspective.

"He's a Westerner," McConnell said. "There are so many cases that have to do with the West, and I also think the cultural sensibilities of the West are different. He's an outdoorsman, and the Supreme Court needs a little bit more geographical diversity."

Maggesto said as a result of being on the 10th Circuit, Gorsuch would have seen many Native law cases under various contexts, helping him gain a deep understanding of the historic precedents.

"Westerners have a lot more opportunities to come across tribal issues throughout the formative years of their legal jurisprudence," he said, adding that judges who primarily come up in the East are less likely to develop an appreciation for tribal law issues.

Endorsed by tribes

Even liberal justices who don't have experience with tribal law can sometimes miss the mark on such cases, Maggesto said. He noted tribal organizations are not partisan entities, as their members can have all kinds of political views, and that Native law cases generally are not inherently partisan.

What matters to tribes in terms of judges is a deep understanding of Native law, which is why — as Democrats plotted to block Gorsuch's nomination to the Supreme Court — tribes endorsed him.

"Judge Gorsuch's record includes a great number of decisions involving tribal governments, tribal people and tribal interests, and he has consistently demonstrated not only a sound understanding of Federal Indian Law principles, but a respect for our unique and closely held cultural values," Alvin Not Afraid Jr., then-chairman of the Crow Tribe Executive Branch, wrote in a letter to Senate leadership, according to Indian Country Today.

In another letter sent to the Senate, Mark Azure, president of the Fort Belknap Indian Community Council, said they did not expect to agree with Gorsuch on every Native law issue but that they believed he was "immensely well qualified" and a "mainstream, commonsense Westerner who will rule fairly on Indian country matters."

In paperwork related to his nomination filed to the Senate Judiciary Committee, Gorsuch listed a case involving a Native American prisoner among the ten most significant he had ever ruled on, ICT reported. His ruling held the prisoner had a right to access a sweat lodge to exercise his religious beliefs.

And in 2020, Gorsuch authored the historic ruling in McGirt v. Oklahoma, in which the court ruled much of eastern Oklahoma, more than 40% of the state, was tribal land. In that decision, he was also the only conservative justice to rule against the state and in favor of tribal sovereignty.

Spending time in Indian country

Elizabeth Hidalgo Reese, a scholar of tribal and federal Indian law at Stanford University, agreed that Gorsuch has a deep understanding of Native law. Historically, however, that's not automatically the case for judges who come from the West or have a lot of experience with such cases, she said.

Justices who have been the most reliable on Indian law decisions, regardless of party, are the ones who "just made the effort to understand this very complicated body of law, not just in the abstract sense but also what it means on the ground," Reese, a member of the Pueblo of Nambé, said.

"That really takes spending time with Indian people, spending time in Indian country," she said, adding that justices can choose to do that before or after they join the high court.

Reese pointed to Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who is from New York and served in the 2nd Circuit, where she would not have seen many Native law cases in the years leading up to her Supreme Court appointment in 2009.

"One of the first things she did when she got on the bench was go to Indian countries and spend time with a group of folks who know and understand tribal law and federal Indian law," she said.

In 2011, Sotomayor became the first Supreme Court justice in over 200 years to meet with a tribe when she visited the Pueblo Indians in New Mexico, ICT reported. She has continued to engage with tribal leaders during her judgeship and has been a reliable vote on Native issues, according to Reese.

Regardless of how justices come to understand Native law issues, Reese said it's "incredibly significant" to have someone like Gorsuch on the bench.

"Sometimes there is no tribal voice in oral argument," she said, noting that in the recent Oklahoma case the parties involved were the state and the criminal defendant, meaning tribes themselves had no voice before the court.

"So having expertise in this area of law, and thinking about tribal sovereignty, is a huge benefit."