Scott Olson/Getty Images

- Soaring lumber costs and a shortage of building lots are holding homebuilders back.

- The lack of housing supply is driving home-price inflation to levels that are weighing on buying plans.

- Millennials are set to drive demand even higher, but soaring costs could stop the buying spree before it starts.

- See more stories on Insider's business page.

The problem is that the US just doesn't have enough homes. The solution might be too expensive for homebuilders' liking.

Home prices are growing at their fastest rate on record, and economists are attributing the tightness to simple economics: Where the rally that famously went bust in 2008 was fueled by risky lending and speculation, today's price growth has more to do with huge demand and inadequate supply. If left unaddressed, the shortage could price millennials out of the market just as they reach peak homebuying age.

The trend isn't promising. Housing starts fell nearly 10% through April after surging the month prior, signaling supply won't bounce back all that soon. The shortfall was partially linked to a drop in construction-sector employment. But other metrics suggest the business case for building homes crumbled last month.

On one end, the materials that go into residential construction rose the most since June, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics' Producer Price Index. Much of this increase was likely tied to lumber prices, which shot roughly 48% higher through the month as bottlenecks weighed on production. It's not as profitable for contractors to build new homes when costs sit so high. And that dynamic is now bogging down the market.

About 47% of contractors added escalation clauses to home contracts last month, according to an April survey by the National Association of Realtors. The clauses let firms raise selling prices as building costs rise. Nearly one-in-five contractors said they're pushing back construction or sales.

Even the land that homes are built on is in short supply. The New Home Lot Supply Index maintained by housing analytics firm Zonda fell 10% in the first quarter to a record low. Even the firms that are snapping up land are running behind on turning those lots into sellable homes. Roughly 242,000 authorized homes hadn't been started yet in April, according to the Census Bureau. That's the highest level going back to 1979.

Together, elevated building costs and fierce competition for lots likely cut into contractors' margins. Housing demand is "showing no signs of letting up," but it might take a while before supply rebounds, Ali Wolf, chief economist at Zonda Economics, said in the May 12 report.

"Builders have been aggressively buying land in different stages of development, and many of these lots will turn into homes for sale in the coming year or two," she added.

In encouraging news for contractors, lumber prices have plummeted for seven straight days and erased most of their upswing in late April. Permits for new residential construction ticked higher in April. Mortgage rates sit at historically low levels, further incentivizing prospective buyers to take the plunge.

University of Michigan

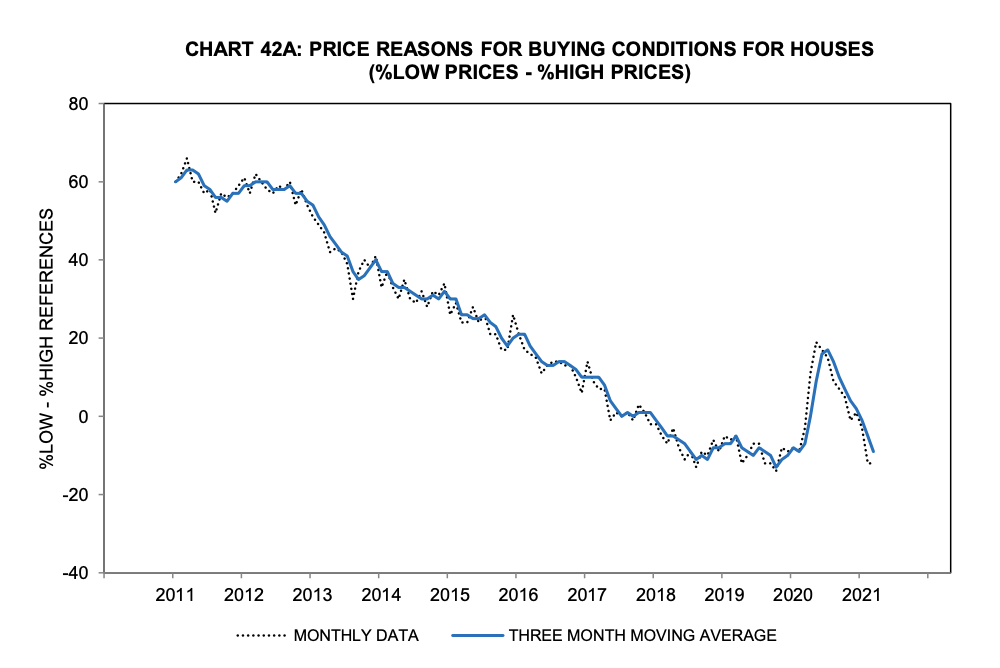

Builders just need demand to still be there once homes are finished. But unless supply bounces back, the barrier to entry might be too high for the average American. Soaring prices are increasingly weighing on buying conditions, according to the University of Michigan's Survey of Consumer Sentiments.

At a time of accelerating inflation across the country, the housing market's health hinges on a lumber-price correction, rebound in building, and resilient demand to power the US out of a severe home shortage.

The prognosis isn't good, according to Goldman Sachs. The bank sees housing starts only hitting 1.5 million per year for the next few years, a pace that's elevated from the last several decades but still below what's needed to meet burgeoning demand from millennials. As Insider's Hillary Hoffower reported in April, not only has the generation faced repeated economic crises, this isn't even its first housing crisis.

Millennials offer homebuilders practically guaranteed business for years to come. The ball is now in the builders' court, and, for the time being, they're running down the clock until the business case improves.