STRINGER/Reuters

- A magnitude 7.2 earthquake struck Haiti on Saturday, causing similar devastation to the quake in 2010.

- Seismologists say it's only a matter of time before Haiti gets hit by another major earthquake.

- That's because the island nation sits at the border of tectonic plates that are moving past each other.

- See more stories on Insider's business page.

The magnitude 7.2 earthquake that struck Haiti on Saturday brought a sense of déjà vu- it was the second major quake to hit the island nation in the last 11 years.

Haiti's 2010 earthquake, a magnitude 7.0, ravaged Port-Au-Prince, killing at least 220,000 people and injuring another 300,000. Seismologists say these two are far from the last.

"We expect more earthquakes. Exactly when or how big we do not know," Catherine Rychert, a geophysicist from the University of Southampton in the UK, told Insider.

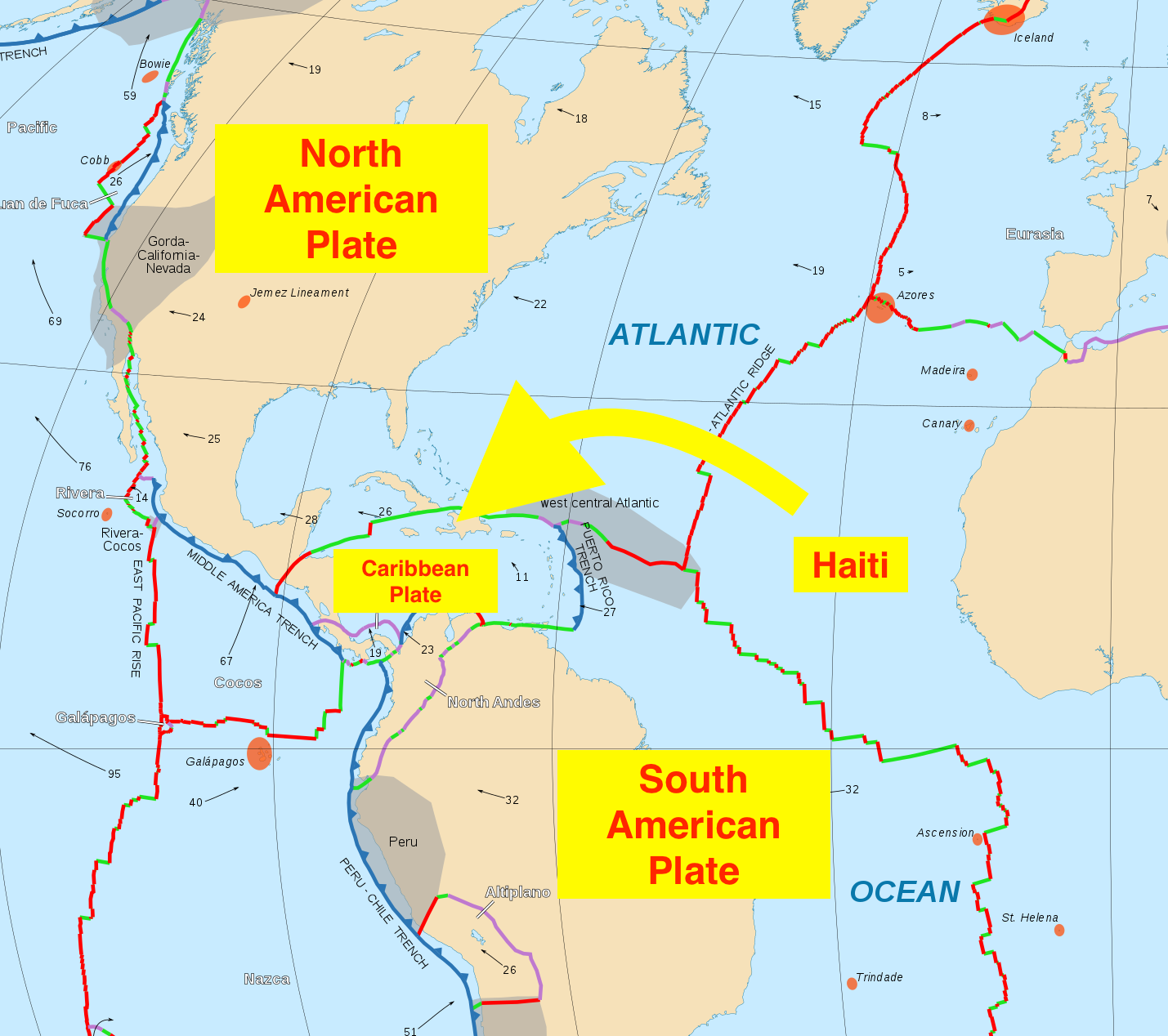

That's because Haiti sits at the juncture of two tectonic plates: the Caribbean and North American plates. These large pieces of Earth's crust surf atop its liquid mantle and get moved around by rising and falling magma and rock. The plates fit together like puzzle pieces, but sometimes the pressure from material below wrenches them apart or shoves them together, causing an earthquake.

On Saturday morning around 8:30 local time, about six miles below Haiti's southern peninsula, the Caribbean plate moved eastward, crawling up and over its neighbor. More than 1 million people felt the resulting shaking across the island of Hispaniola – which Haiti shares with the Dominican Republic – as well as in Jamaica, Cuba, and Puerto Rico.

At least 1,419 people are dead and 6,000 are injured in Haiti, the Associated Press reported. That, however, is likely an undercount by an order of magnitude, according to the US Geological Survey. There's a 38% chance fatalities will exceed 100,000.

There's a chance an even larger quake is coming

Wikimedia Commons

The boundary between tectonic plates is called a fault; 95% of earthquakes happen on these margins. Under Hispaniola, two faults crisscross, but Haiti's major quakes have all been traced to the the Enriquillo-Plantain Garden fault system, which travels right under Port-Au-Prince. The 2010 earthquake and Saturday's disaster both happened along that fault, and both involved the same type of plate motion.

So it's possible the former led to the latter, Rychert said: "Sometimes when strain is released on one section of a fault it can cause stress to build on other parts of the fault system."

USGS experts said another earthquake could be coming, given that 5% of earthquakes occur as part of a sequence.

"It's possible to have another earthquake as large or larger than this recent one," USGS seismologist Paul Earle told Insider. "It's a small chance but not non-existent."

(AP Photo/Joseph Odelyn)

Earle said the agency is most worried about another quake hitting closer to Port-Au-Prince. The epicenter of Saturday's quake was just south of Petit Troup de Nippes, 78 miles west of the capital.

"Sometimes in fault systems, you'll have a fault rupture and then you'll have another rupture on a segment further down," he said.

But predicting that future quake is nearly impossible, Earle added. And regardless of whether another quake comes, aftershocks from Saturday's are expected to continue over "the next week, month, and beyond," the USGS said.

A 5.2-magnitude aftershock hit 20 minutes after the first quake, and Earle said people in the southern part of Haiti "will be feeling anywhere from a few to potentially hundreds of smaller earthquakes in the magnitude 3.0 range."

The fault under Haiti may have entered an 'active' period

Ramon Espinosa/AP

Haiti's seismological history also suggests more temblors could be on the horizon.

Big quakes struck in 1701, 1751, and 1770, after which the region settled into a 240-year-long quiet period. Then the big 2010 earthquake shattered that peace. A 2012 USGS study suggested the disaster marked "the beginning of a new cycle of large earthquakes on the Enriquillo fault system after 240 years of seismic quiescence."

The report predicted, accurately, that Haiti and the Dominican Republic should prepare for future devastating earthquakes.

Periods peppered with quakes on a fault line are normal, according to Earle, and there's little rhyme or reason to their timing, as far as seismologists can understand.

"You randomly get groupings of quiet times and times that are more active," he said, "it's a bit like listening to popcorn popping. Sometimes there are less or more pops at once."