- After reading the script for "The Social Network," Peter Thiel didn't like how the film portrayed him.

- He came up with the fellowship idea while on a plane, and the program's poor planning was disastrous for fellows.

- Only a few fellows found success, and some struggled with mental health issues and drug abuse, writes Max Chafkin in his new book.

- See more stories on Insider's business page.

When Peter Thiel announced the Thiel Fellowship at a TechCrunch conference in 2010, he proposed something unprecedented: he would dole out $100,000 to two dozen teenagers who had big ideas and were willing to drop out of school to pursue them.

It would be worth it, he promised – he was going to help them "change the world."

But for some Thiel fellows, the program ended up being "disastrous," according to a new biography about the billionaire entrepreneur and venture capitalist.

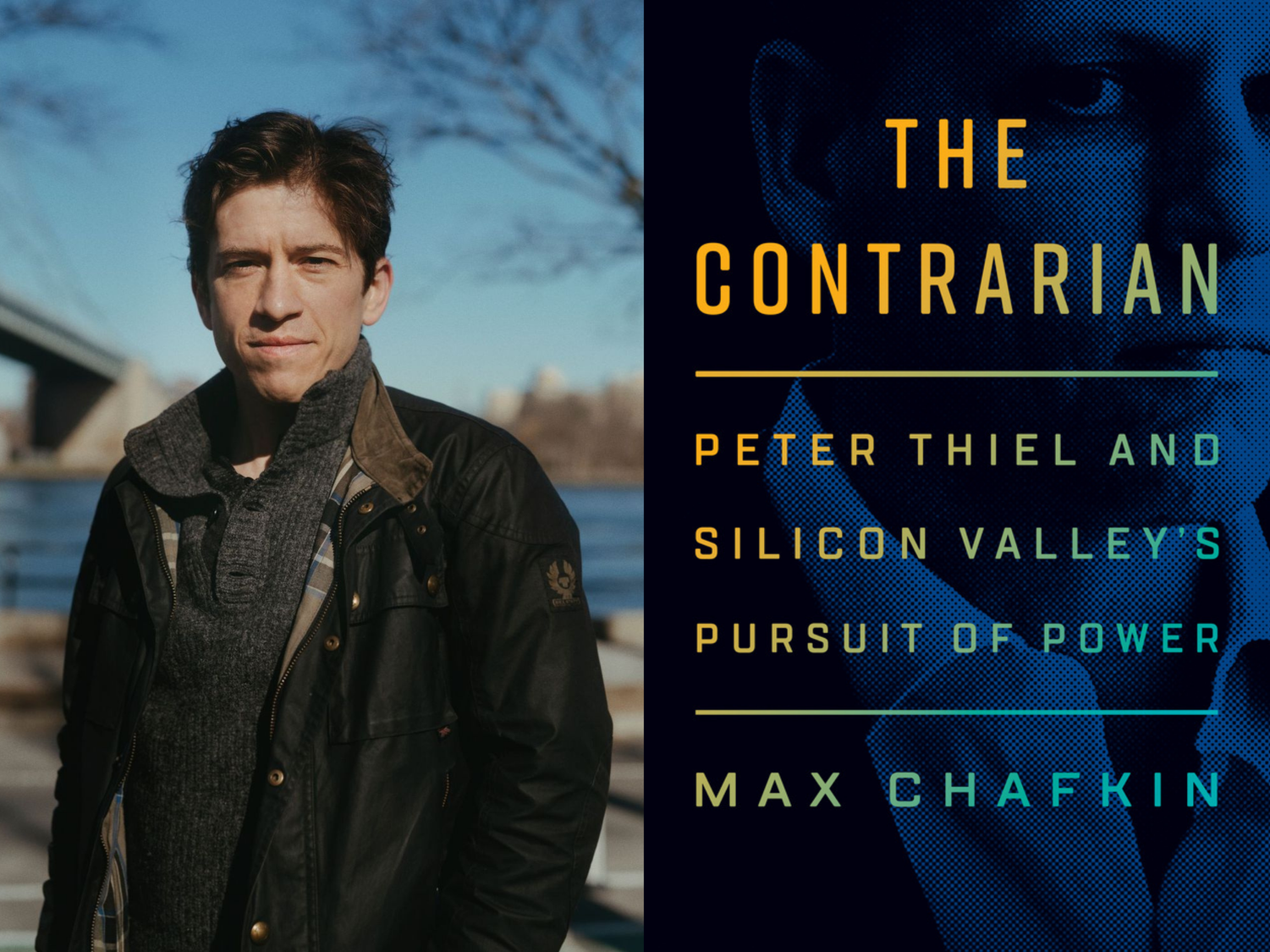

"They showed up in California only to find out that the actual execution of the fellowship was basically an afterthought once Thiel had achieved his marketing goal," wrote Max Chafkin in "The Contrarian: Peter Thiel and Silicon Valley's Pursuit of Power," released today.

Caroline Tompkins and Penguin Press

At the time, Thiel was trying to boost his public perception. After reading the script for Aaron Sorkin's "The Social Network," he was agitated by how the film was going to portray him: as the ruthless investor who helped Zuckerberg push out his partner.

On the plane to San Francisco the day before the TechCrunch announcement, Thiel and his team decided that creating a fellowship was the answer and that they'd hammer out the details later.

The fellows - among them undergrads from MIT, Harvard, and Yale, and a Stanford neuroscience PhD student - arrived in San Francisco expecting vast networking opportunities with investors and Silicon Valley big shots, career-shaping mentorships, and an education more valuable than what the top-tier universities they left could offer.

Instead, they were met with a tiny and unqualified staff, zero structure, and no office hours.

"It was college without the classes, a residential community, or studying-in short, most of what was enriching about college," wrote Chafkin.

The fellows, some as young as 16, had never been in charge of their own finances before. They were provided housing for just the summer, all of them squeezed into one house. Then, they had to fend for themselves. While $100,000 sounds glamorous, it was broken up into two annual payments, and taxes and rent drained plenty of it.

Many fellows ended up feeling like "second-class citizens" in the program - Thiel would show favoritism towards (and invest money in) a few choice fellows, even though there was a "rule" that Founders Fund would not invest in anyone. This loose policy left the unlucky majority feeling like failures.

And although all fellows were invited to some networking events at Thiel's house, they were hyped-up and "the most depressing parties you've ever been to," a former fellow told Chafkin. Chafkin explains that the super lucky ones could expect to have breakfast with Thiel and a group of other entrepreneurs, where Thiel would ramble on about something, take a bite of his now-cold breakfast, and then order a second breakfast.

Many fellows "just felt lost."

One fellow supposedly experienced mental health issues and drug addiction, and another got caught up in a Ponzi scheme. The staff failed to act quickly enough to help either of them, past fellows told Chafkin.

Startup incubator Y Combinator also invested $100,000 to budding startups, but it provided key resources that the Thiel Fellowship didn't: biweekly office hours and social events that created a sense of community.

"I was like, 'dang here I am in Silicon Valley, I don't know anyone at Stanford. I can't just go to a bar since I'm under 21. I can meet with any CEO, but I don't need that. I just need someone to hang out with," one Thiel fellow told Chafkin.

By the program's fourth year, few Thiel Fellows had achieved success in their endeavors.

Thiel then replaced the program's directors in 2015 and changed the rules to bring in fellows as old as 22.

And if you're wondering what happened to those fellows who never "made it" in the conventional sense, according to Chafkin they were taken off the list for alumni emails or events and walked away empty-handed: without alumni connections, a college degree, or having changed the world.

One fellow told Chafkin that "they'd come to regard their time with Thiel not as some profound intellectual exercise, but rather, 'a super-smart PR move.'"