Yuqing Liu/Business Insider

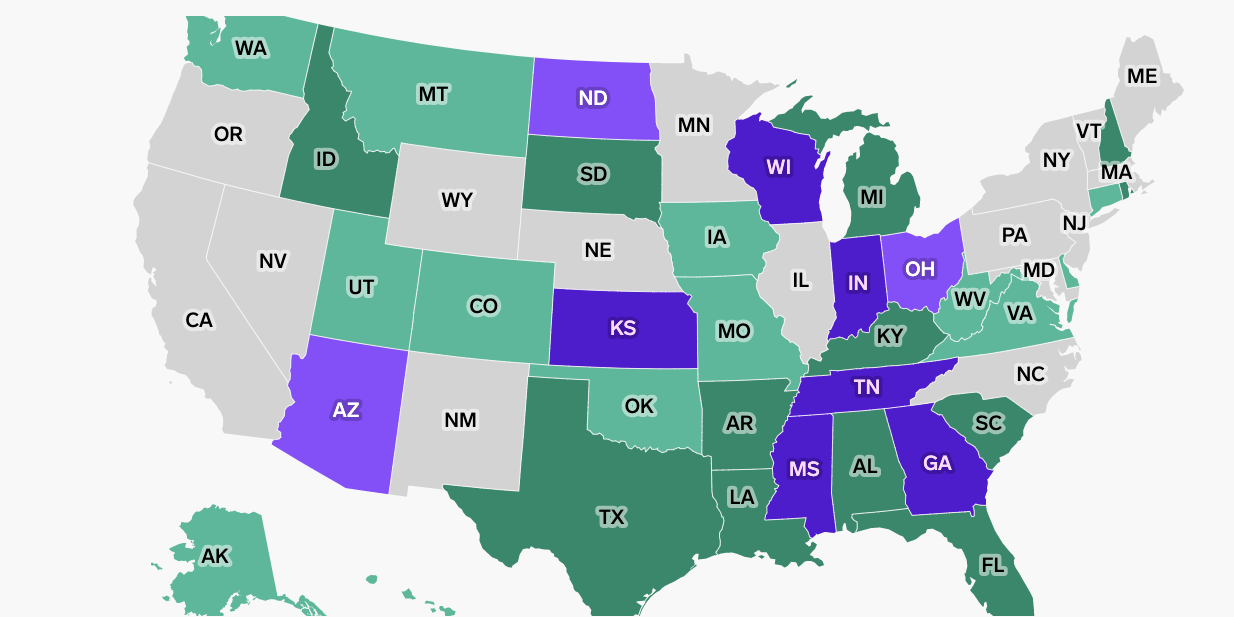

- This November, 34 states will require voters to show identification at the polls in order to cast a ballot.

- Voter ID laws can either be strict, in which a voter must cast a provisional ballot and later show proof of identity, and non-strict, in which a voter can sign an affidavit affirming their identity to vote.

- In some states, you may also need to submit a photocopy of your ID with your ballot application or with your ballot itself.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

This November, 34 states will require voters to show identification at the polls in order to cast a ballot on Election Day.

Voter ID laws come in four categories: photo and non-photo, and strict and non-strict.

States with photo ID requirements mandate voters to bring a state-issued driver’s license, non-driver ID or voter card, US passport, or a military, tribal, student, or state employee card to the polls in order to vote. Most states have exemptions to these rules for voters who cannot be photographed due to their religious beliefs.

Non-photo ID states allow voters to bring official government mailings or other recent documents that bear the voter’s name and address, like a utility or rent bill, pay-stub, or bank statement.

Non-strict states allow voters without the required documentation to cast a sworn affidavit or reasonable impediment declaration or to have a poll worker vouch for them in order to vote, while strict states require voters to cast a provisional ballot and later provide additional proof of residency to their election officials in order for their vote to count.

Different states have varying requirements on whether a photo ID must be current or if it can be expired in order to be used to vote, so be sure to both verify the exact requirements with your state and local election offices and check if your state's Registry of Motor Vehicles has extended the expiration deadlines for licenses or ID cards during the pandemic.

If this sounds confusing to you, you're not alone. Multiple nonprofit organizations dedicated significant resources to helping voters get an ID in their state in the pandemic. One group, VoteRiders, is almost entirely devoted to helping people get IDs this fall, the group's founder and board chairwoman Kathleen Unger, a longtime voting expert and lawyer, recently told Insider.

"Based on a Brennan Center study showing that up to 11% of voting-age Americans do not have a current government-issued photo ID, that translates into about 25 million eligible voters," Unger told Insider. "There are many millions more who are so confused and intimidated by these complicated and onerous voter-ID laws that they won't vote, even though they have a valid ID."

Voter ID laws weren't in use in any state before the 21st century, until the 2002 Help America Vote Act required some first-time voters who registered by mail to present identification for voting in federal elections, opening the door for states to impose similar requirements.

Indiana was the first state to impose a voter ID law for the 2006 election, with dozens of states following suit in the next several years.

In the mid-2010s and 2020s, Republican state legislatures and attorneys argued that such laws are justified to prevent in-person voter impersonation, a type of voter fraud that multiple comprehensive studies have found is vanishingly rare to the point of being almost non-existent.

A 2014 study from Loyola University Law School professor and elections scholar Justin Levitt, for example, found just 31 credible cases of voter impersonation between 2000 and 2014, a time period during which over one billion votes were cast.

The conservative Heritage Foundation, which maintains a non-exhaustive but comprehensive database of voter fraud cases, has documented just 13 cases (criminal convictions, civil penalties, or official/judicial findings), of in-person voter impersonation in the past 20 years compared to 186 cases of voter registration fraud and 193 cases of absentee ballot fraud.

An analysis from the Brennan Center for Justice also found that many reported cases of voter impersonation are due to clerical mistakes or identity mismatch and not actual malice, concluding that an American is more likely to be struck by lightning than commit voter impersonation.

Some studies have also found that ID laws can disproportionately disenfranchise low-income voters and voters of color. While many states now provide state ID cards at no cost to the voter, obtaining the underlying documents, like a birth certificate or social security card, can be costly.

"The folks who are disproportionately impacted by these ID laws are those who do not have a current driver's license in their states," Unger told Insider. "And who are they? They are communities of color...they are students and other young people, they are older adults who are no longer driving if they ever did. They are voters with disabilities. They're low-income individuals and they're women, because some states require an exact match between the name on your ID and the name by which you're registered to vote."

Black Americans and voters of color are less likely than whites to hold the required ID to vote and therefore are more burdened by voter ID laws, multiple studies have found. A nationwide study of validated voter data from 2017 found that gaps between Black and white turnout and Latino and white turnout were significantly wider in states with strict voter ID laws than in states with non-strict voter ID.

Similar state-level studies from Texas, Michigan, and Indiana also found that Black and Latino voters are less likely to possess the proper photo ID identification to cast a ballot.